What Could a Shift Toward a Whole Child Approach Look Like in Schools? An Emphasis on Mental Health

Education Domain Blog

The following is an excerpt and transcript of the Aurora Institute 2019 Symposium opening keynote address, delivered on October 28th by Chan Zuckerberg Director of Whole Child Development Dr. Brooke Stafford-Brizard. In the address, titled Broadening the Definition of Student Success: A Spotlight on Mental Health, she dives deeply into what it could look like to integrate mental health, as one pillar of whole-child development, into schools. She offers two riveting examples from the teacher and learner perspective on how a school could create space for the personal growth, connection, and trust that drive academic development.

I want to thank the entire [Aurora Institute] team for having me here tonight to kick off the coming days of conversation focused on the future of learning because that is core to the vision we have at the Chan Zuckerberg Education Initiative. Our vision is grounded in that broader definition of success. We focus on that because we know from research and from the wisdom and experience of practice that far more than the academic competencies and the high school diploma are necessary for success in young adulthood. But if we only focus on those competencies, that is where our resources will go, and that is where our energies will go. And so we have to change that North Star to really reflect what we want for our kids to be successful in young adulthood.

We’re committed to leveraging personalization in this effort, and our definition is very similar to what Susan shared. We believe that personalization is about deeply understanding the unique passions, strengths, needs, and context of every learner and tailoring the learning environment to meet those needs. As we think about the whole-child approach that that requires, I want to ask you a few questions. What comes to mind if you could picture a student who is thriving academically?

Something like this?

What about a student who’s thriving physically?

Something like this?

Now, if I asked you to picture a student who’s thriving in their mental health, what does that look like?

Was that a little bit harder?

Did you start to think about maybe what they weren’t: weren’t stressed, weren’t anxious, weren’t disconnected. We have a really hard time bringing a picture of mental health as something that’s asset-based, and drawing from key strengths. And without that picture, it’s really hard to then move to the skills and conditions that support that development.

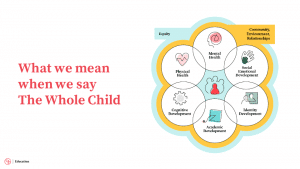

When we think about the whole child, we think about six key domains of development, and mental health is one of them. Across all of these domains, we anchor in that asset-, strength-based approach. So we defined whole child to be inclusive of academic development, which is an important point in its own right: that whole child isn’t everything but academic. We also name cognitive development, identity development,  social-emotional development, and physical and mental health. Because you cannot tease these apart in the human being—whether it’s a child, an adolescent, or an adult—we work very hard to think about how we support integration and practice. That’s how we believe school should look.

social-emotional development, and physical and mental health. Because you cannot tease these apart in the human being—whether it’s a child, an adolescent, or an adult—we work very hard to think about how we support integration and practice. That’s how we believe school should look.

Now, before I move into what the shift toward a whole child approach might look like, I want to ground us in a few more points of this framework.

One is the deep connection to these skills and the context that our students are in. We do not want this to be an individualistic framework because we know from the science, the development of all of these areas is deeply grounded in the way that students are engaging with their community, with their relationships, and with their environment.

We’re also deeply focused on equity when it comes to this framework, and that means focusing on the assets that students bring from their backgrounds, their cultures, and their experiences, and ensuring that our learning environments reflect those assets. If we see gaps in performance that are correlating to race or income, we are deeply focused on the skills that we need to develop in those students, but we’re just as focused on the environment that they’re within. So it’s fantastic if we can identify practice that supports a student’s sense of belonging, but unacceptable to send that student back into an environment that might be emotionally unsafe or full of bias. So all of our investments in our focus hold the individual in context, hand in hand.

With this approach in mind, I want to focus tonight on one component of this framework and do a deeper dive into mental health. I want to demonstrate the demand that we see for mental health in the field and the huge need for the focus on this. Then I want to focus on two goals. One is clarity and what we mean by that. As Susan pointed out, definitions matter. I want to get clear on what it actually looks like to bring this into practice. So we can move from that why to the how and really understand some of the shifts that we need to make in our schools. Before we make that shift, I want to tell a couple of stories so we can really understand what a typical student and a teacher might be experiencing in today’s schools.

This is Christopher.

He’s 14, ninth grade in a typical high school in a mid-size city. By the time he’s on the bus in the morning, his head is swimming with thoughts and emotions, and only some of those are connected to his upcoming school day. On the family side, his father struggling with a very serious illness, and Christopher has unresolved questions and frustrations and fear about that. He’s also navigating the increasing complexity of adolescent relationships, further complicated by the fact that he is in his new space of a high school environment. And yes, he’s thinking about his upcoming day, and the growing deadlines and responsibilities associated with his school work. But because he sees that upcoming day as “his job,” to enter that school as a student, he does his best to kind of compartmentalize and suppress the other emotions that he’s feeling. He walks into that first period math class trying to do that without talking to one adult or one peer. Throughout his day, he tries to stay under the radar, answering a few questions so he doesn’t set off any alarms for teachers, which he’s done for one teacher with whom he’s fairly close. But they have not been able to find that time to connect in the busy day. So he’s back on the bus at the end of the school day, and he has all of these unresolved emotions. He’s exhausted from trying to suppress them and keep them from distracting him, and he’s trying to do it again so we can get to work on his homework.

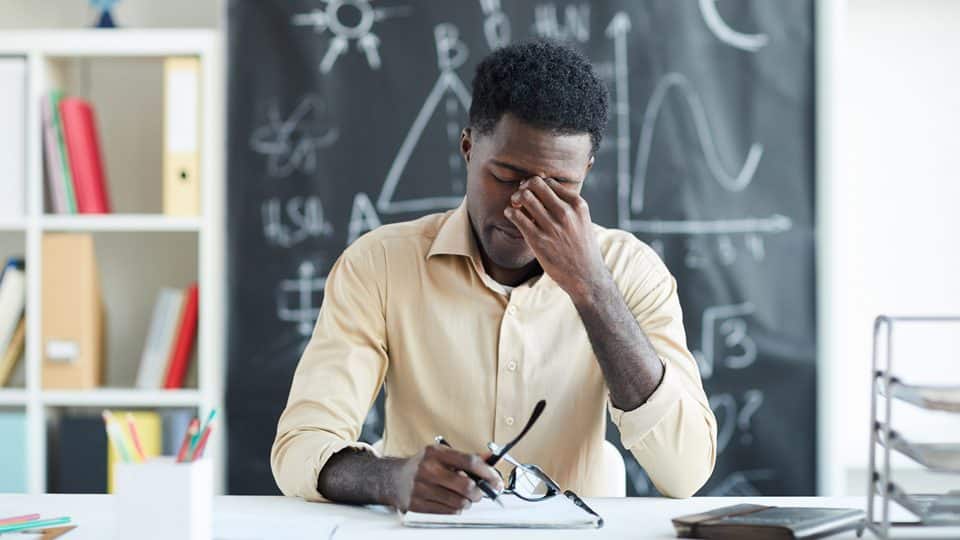

Let’s focus on one of Christopher’s teachers.

Before Kevin Hillman’s feet touch the ground in the morning, he feels behind. He and his wife race to get themselves and their two kids out of the house. His mind is shifting between his family,  his many students—a certain number of which he’s very concerned about and constantly come to mind—and the lessons he’ll teach as a science teacher that day. Those lessons are underway before he knows it, and his day is kind of a toggle between the joy and engagement he feels when he’s immersed in those lessons, in the lab work with the students. And then, class by class, he also feels a growing sense of stress and frustration with the students he can’t reach. Whether they’re actively acting out or just disconnected, he knows that there are serious issues driving that, and he wants to better connect with those students. But again, he doesn’t have the time. Christopher is one of them. And so when he ends his day, it’s a combination of gratitude for his family and his relationships, frustration that he hasn’t reached those kids, stress because the stress that they’re feeling becomes his stress, and a sense of inadequacy that he can’t reach all kids.

his many students—a certain number of which he’s very concerned about and constantly come to mind—and the lessons he’ll teach as a science teacher that day. Those lessons are underway before he knows it, and his day is kind of a toggle between the joy and engagement he feels when he’s immersed in those lessons, in the lab work with the students. And then, class by class, he also feels a growing sense of stress and frustration with the students he can’t reach. Whether they’re actively acting out or just disconnected, he knows that there are serious issues driving that, and he wants to better connect with those students. But again, he doesn’t have the time. Christopher is one of them. And so when he ends his day, it’s a combination of gratitude for his family and his relationships, frustration that he hasn’t reached those kids, stress because the stress that they’re feeling becomes his stress, and a sense of inadequacy that he can’t reach all kids.

What would it look like if Christopher and Mr. Hillman had that space to process those emotions so they could feel more present to make those connections and build those relationships that are so important to them? What would it look like to allow them to tap into the purpose and passions that drive why they’re where they are? We know part of it looks like them both nailing the “arm cross” [and appearing happy and satisfied].

So I want to paint the picture of what that can look like.

One of our partner schools is Valor Collegiate. This is a charter school in Nashville, Tennessee. It has a really unique founding story. Todd Dickson was a traditional educator and school leader, and his identical twin brother Darren had expertise and background in the clinical space, in social work. Together, they co-founded a school that held academic rigor and development right next to social, emotional, and mental well-being of their students with the vision that that would actually drive academic rigor and development. And it has. Valor has performed in the top 4 percent of state performance for the past several years. One of the practices that they have is a circle. This is where students and teachers come to reflect on their personal growth, to build as a community, and also to restore. The clip I’m going to show you is a student who’s come to engage in that restoration and take ownership of a disruption in class. What I really want you to focus on though, is the reaction of the teacher and the fact that they had the space to do this.

I’ve seen again and again the impact that that practice has on students’ personal growth, on the growth of Valor is a learning community, grounded in connection, trust, and vulnerability. One of the reasons it’s so impactful is because the Valor team believes if they’re going to ask this of students, then they have to ask it and support their adults in the same practice. And so I also want to share a clip of what that looks like in the adult community at Valor.

The principles and the vision that undergird what you see in that circle permeate that community. It impacts the way that they staff, the way that they schedule, and the way that they’re bringing their instructional leadership to the classrooms. I see Todd bring that level of coaching and mentoring and support to the academic lens. Darren is doing the exact same thing when he’s thinking about social-emotional and mental well-being.

There is incredible demand in the field for this.

Dr. Brooke Stafford-Brizard is Director of Whole Child Development at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Continue to watch this space for more from her 2019 Aurora Institute Symposium keynote address. See more highlights from the entire conference on this webpage.