ACTIONS – Ideas and Strategies for District Leaders

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the ninth post in a series that aims to make concepts, themes, and strategies described in Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing, and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education accessible and transferable. Links to the other articles in the series are at the end of this post.

This is the ninth post in a series that aims to make concepts, themes, and strategies described in Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing, and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education accessible and transferable. Links to the other articles in the series are at the end of this post.

I spent years in a district leadership role trying to help schools navigate the shift toward personalized, competency-based education. One of the the many things I learned during this time was that in order to help schools innovate, I also had to help central office innovate. Specifically, I had to think differently—first for myself, and then for others—about the roles of central office in navigating and sustaining innovation.

In my experience, being called “someone from the district” by someone in a school could carry any number of connotations: someone who made rules, someone who added to teachers’ plates, someone who didn’t get what things were really like in a classroom. Now, this wasn’t one hundred percent true for me, and it’s certainly not one hundred percent true in every district. Still, I share this experience because I think it reflects a concern we have all seen, felt, or experienced at some point: that central office and schools are not always on the same page about how to approach innovation, or how to help teachers help kids.

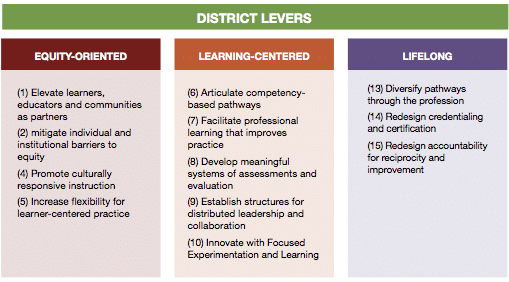

However—and this is a BIG however—there are lots and lots of examples that prove this perception wrong. More specifically, there are lots and lots of examples of district leaders who play very different roles in orienting, enabling, and supporting learning and teaching on the ground. This is one of big ideas I want to get across in Moving Toward Mastery: that district leaders can play powerful roles in creating the conditions where teachers can learn and grow so that students can learn and grow. Toward the end of the report I describe the leverage that district leaders have in their roles (page 68). But, I stop short of describing specific actions they can take. This post picks up where the paper left off, offering three big ideas and ten action ideas for district leaders who are trying to grow, develop, and sustain educators for competency-based education.

However—and this is a BIG however—there are lots and lots of examples that prove this perception wrong. More specifically, there are lots and lots of examples of district leaders who play very different roles in orienting, enabling, and supporting learning and teaching on the ground. This is one of big ideas I want to get across in Moving Toward Mastery: that district leaders can play powerful roles in creating the conditions where teachers can learn and grow so that students can learn and grow. Toward the end of the report I describe the leverage that district leaders have in their roles (page 68). But, I stop short of describing specific actions they can take. This post picks up where the paper left off, offering three big ideas and ten action ideas for district leaders who are trying to grow, develop, and sustain educators for competency-based education.

THREE BIG IDEAS

Let’s start with three framing ideas about the roles district leaders can play in the shift toward personalized, competency-based education.

Districts can orient. The shift toward personalized, competency-based education is a massive one. A key role for district leadership is articulating and modeling a shared vision for change. While it is vital that teachers, leaders, and communities shape this vision, it is incumbent upon district leaders to hold the vision at the forefront. Concretely, this means helping teachers, students, and communities understand what the vision means for them, what they are being asked to do, and what supports are available to them. District leaders share the helm while constantly orienting and guiding the ship.

Districts can enable. In her work “Implementing competency education in K–12 systems: Insights from local leaders,” Chris Sturgis writes, “top-down approaches undermine any efforts to create an empowered staff who will take responsibility for ensuring students are learning. [And] when employees look to the next level up to answer questions and resolve issues, it undermines the culture of learning and is a lost opportunity for building problem-solving capacity within the organization.” Chris is communicating a vital message for district leaders: navigating the shift to personalized, competency-based education requires enabling leadership at all levels. One of the most important things district leaders can do is to cultivate an environment in which teachers and school leaders have the clarity, autonomy, and support to try new things, learn, and make decisions that are best for kids.

I would only add one thing to Chris’s important words: it is important to check your espoused culture against your lived culture. I have known well-intentioned leaders who try to create (and believe they are creating) a culture of empowerment, but whose staff and communities still experience spoken or unspoken set of pressures that tip the scales toward compliance. Unintended barriers, outdated policies, and mixed messages can keep a culture of compliance in place even when leaders are trying diligently to cultivate the opposite.

Districts can support. In his publication Bridging the Gap Between Standards and Achievement: The Imperative for Professional Development in Education, Richard Elmore writes about a concept called “reciprocal accountability.” While there are several dimensions to this concept, here’s one I think is vital: “For every increment of performance I demand from you, I have an equal responsibility to provide you with the capacity to meet that expectation.” Districts undergoing the shift toward personalized, competency-based education will inevitably ask their teachers to make significant shifts in their mindsets, knowledge, skills, and day-to-day actions and routines. Doing this effectively requires providing ample and aligned supports: time to learn, resources to learn, systems that support learning, and communities of practice in which learning is possible. See the earlier post on learning-centered practice for ideas about what this can look like, and where to get started.

TEN DISTRICT LEADER ACTIONS

Get Started

- Engage your community to create a vision. Convene stakeholders from across your district, ensuring that you include voices that have been historically marginalized or excluded. With diverse perspectives at the table, conduct a landscape assessment of current practice. How are teachers learning and growing? What impact does this have for student learning? What’s working? What’s not? What aspects of professional practice are in or out of alignment with personalized, competency-based education? Based on this assessment, articulate a clear and compelling vision. When all students are learning and achieving at high levels, what will teaching look like?

- Chart a roadmap. Having an idea about where you want to go is a vital foundation for change. Knowing how to get there is the next step. After setting a vision with your community, create a roadmap for change. What does it look like to get started, move forward, and then sustain comprehensive change? Mistakes and surprises are inevitable. What information will you look at to know what is working and what is not? How will you learn as you go and adjust course? Who do you need to engage along the way?

Create Cultures of Empowerment, Learning, and Growth

- Empower schools. Articulate a vision for empowerment. Before deciding what’s “tight and loose,” or which decisions lie with which leaders at which levels, define what it means to be a system of empowered schools. What is the purpose of empowerment? How does empowerment serve students, teachers, and leaders? What conditions are necessary to make empowerment work well? With clarity about this vision, leaders can then enact policies and create systems that strategically distribute leadership and decision-making to schools.

- Address barriers to empowerment. Often, empowerment on paper does not equal empowerment in practice. Education Resource Strategies and the Center for Collaborative Education published a report for the Boston Public Schools detailing the promise and the many challenges of enabling empowerment in practice. This may be a helpful resource for leaders wanting clarity on the types of competing priorities, unintended barriers, and capacity gaps that can inhibit empowerment.

- Redesign evaluation for continuous improvement. Creating a culture of continuous improvement is key for personalized, competency-based education. Assessment and evaluation are critical drivers of continuous improvement: meaningful systems of student assessment, teacher evaluation, and school quality assessment create conditions in which students, teachers, and leaders can constantly learn and improve. There is a lot that goes into creating such systems. Check out iNACOL’s blog on continuous improvement and brief on assessment for two helpful starting points.

Cultivate Conditions and Systems for Adult Learning

- Define teacher competencies and a pedagogical framework. Designing a system of professional learning starts with getting clear about what teachers need to know and be able to do in a personalized, competency-based system. More specifically, it starts with getting clear about the outcomes that are expected for students, the types of learning experiences and environments that will support those outcomes, and then what teachers need to know, believe, and be able do do in order to create those experiences and environments. Check out pages 15 through 18 in Moving Toward Mastery for guidance on how to get started.

- Articulate competency-based professional learning pathways. In competency-based systems, students advance along personalized learning pathways. The same must be true for teachers. Instead of assuming that teachers will move in lockstep through their professional learning and along uniform trajectories of professional growth and advancement, competency-based systems articulate personalized, competency-based professional pathways for teachers. What does this mean? It means teachers can follow personally meaningful learning paths. It means they demonstrate their learning as they grow. And, it means they have opportunities to differentiate and specialize in their roles as they advance. Micro-credentials can be very powerful levers for this type of change. Check out this micro-credentials implementation roadmap from Digital Promise.

- Align learning experiences. A key step in creating conditions for adult learning is figuring out how to help teachers experience personalized, student-centered learning so that they can create those same experiences for students. This shifts a district leader’s purpose from “ensuring all teachers know what personalized, student-centered learning is” to “helping schools create the conditions in which teachers can cultivate personalized, student-centered learning.” The answer to this question might include investing in coaching, communities of practice, and anywhere-anytime learning technologies. And often, it will mean reallocating resources like time, technology, and people.

Mitigate Individual and Institutional Bias

- Promote diversity and inclusion. A diverse and representative teaching force helps all learners achieve personal and academic success, especially learners of color. This matters in the shift to competency-based education because at its core, competency-based education is about increasing equity. District leaders can play important roles in deepening equity-focused practice by hiring, supporting, and retaining educators who reflect their students, and creating inclusive professional cultures for all educators and staff. See page 26 of Moving Toward Mastery for ideas about where to get started.

- Prioritize culturally responsive practice. Getting to equity involves increasing cultural responsiveness. Certainly this is true in the classroom, and district leaders can play important roles in prioritizing and supporting professional learning that builds teachers’ capacities as culturally competent practitioners. It is also vital to build this capacity in central office. Supervisors, curriculum developers, budget analysts, professional coaches—all of these roles need to understand what culturally relevant practice looks like in the classroom, and in their own positions. For district leaders, helping shift learning and teaching toward cultural relevance means building capacity at all levels.

Read the entire series:

- Introducing Moving Toward Mastery

- Entry Points: Moving Toward Equity-Oriented Practice

- Voices: Developing Teacher Mindsets

- Entry Points: Moving Toward Learner-Centered Practice

- Actions: Ideas and Strategies for School Leaders

- Voices – Lisa Simms on Leading and Sustaining Innovation

- Entry Points – First Steps Toward a Lifelong Profession

- Voices – Jennifer Kabaker on Changing the Narrative and Recruiting Lifelong Educators

About the Author

Katherine Casey is Founder and Principal of Katherine Casey Consulting, an independent organization focused on innovation, personalized and competency-based school design, and research and development. Katherine was a founding Director of the Imaginarium Innovation Lab in Denver Public Schools, supporting a portfolio of almost 30 schools across Denver and spearheading the Lab’s research and development activity. Katherine was a founding design team member at the Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, Denver’s first competency-based high school. Prior to her time in Denver, Katherine worked in leadership development, philanthropy, public affairs and higher education. She received her BA from Stanford University and her Doctorate in Education Leadership from Harvard University.

Katherine Casey is Founder and Principal of Katherine Casey Consulting, an independent organization focused on innovation, personalized and competency-based school design, and research and development. Katherine was a founding Director of the Imaginarium Innovation Lab in Denver Public Schools, supporting a portfolio of almost 30 schools across Denver and spearheading the Lab’s research and development activity. Katherine was a founding design team member at the Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, Denver’s first competency-based high school. Prior to her time in Denver, Katherine worked in leadership development, philanthropy, public affairs and higher education. She received her BA from Stanford University and her Doctorate in Education Leadership from Harvard University.