An Update From Oregon’s Business Education Compact

CompetencyWorks Blog

As you all know, Oregon is a state leader in proficiency-based education, first establishing credit flexibility in 2002. (You can learn about their progress in putting together a variety of elements on the wiki.)

As you all know, Oregon is a state leader in proficiency-based education, first establishing credit flexibility in 2002. (You can learn about their progress in putting together a variety of elements on the wiki.)

The Oregon Business Education Compact (BEC) has been active in advancing proficiency-based education, supporting pilot schools and providing training to educators on classroom practices. In some ways, the conversion to proficiency-based education has started in classrooms across Oregon, which embraced standards-referenced grading. Now, schools are opening their arms to the more systemic whole-school conversion.

An aside: We believe at CompetencyWorks that it is at the point of converting an entire school to a proficiency-based model that we begin to see real benefits to students and teachers. It is only at the school level that resources can be organized so that every student is in the zone (the zone of proximal development, that is). It also requires a full-school commitment to move to standards-based or competency-based (implying application of skills) models in which students continue to learn until they master the skills rather than being passed on to the next grade or course with gaps in knowledge.

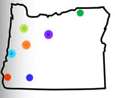

So we wanted to get an update as a new initiative funded by the state of Oregon is investigating what a full transformation of a school would look like. BEC is working with four schools (one grades 3-7, two middle schools, and one high school) and three regions (with at least five districts served in each region) of the state. The goal of the project is to better define the practices that need to be in a place for a school to fully convert to proficiency-based education:

The schools in the initiative are hoping to:

- Agree on elements of a common proficiency definition and practices; be able to describe/define it for all stakeholders, including students and parents, in a way that is clear and meaningful.

- Select and/or design assessments that are aligned to the targeted standards; develop routine protocols that use the results to create multiple and meaningful learning activities.

- Plan for frequent and purposeful formative and summative assessments to help guide and frame instructional choices that reflect student personalization in lessons.

- Develop classroom interventions that help each student reach proficiency in the selected standards.

- Create and implement plans and practices that move students to the next learning level when they have demonstrated they are proficient in the selected standards.

A team from Madras HS in Madras, OR has visited California’s Lindsay Unified High School to better understand how to operationalize “assessment when ready” and the fluid movement of students through courses and curriculum. In October, a team from Lindsay will visit Madras HS. Representatives from 15 other high schools will have a chance to talk with the Lindsay team about these same issues, as well.

The initiative (it’s being evaluated by a team from EPIC) also is looking at how to strengthen the systems of assessments needed to support students, educators and school performance. The focus is on thinking more broadly than the state assessments (Oregon is part of SBAC) so that the schools’ assessments include “sufficient evidence of student demonstrated knowledge and skills that meet or exceed defined levels of performance.” They also want to draw on the strengths of students and educators as potential assessment designers and evaluators in the learning process. (This may sound familiar – Finland’s education system emphasizes that the assessment expertise must be firmly rooted within the schools. Teachers know exactly what proficiency looks like, how to assess, and how to provide productive feedback and additional instruction if needed. Peer- or self-assessment builds the capacity of students to reflect upon their own learning and building their skills as learners.)

The big challenge for districts and schools in Oregon, as across the country, is the lack of adequate information systems. Should they spend scarce resources on one of the new systems designed to support competency education, or wait for the SIS vendors to upgrade their products? With the state leadership looking at Pre-K/20 systems, it’s hard for districts to take the risk to invest in IT. It’s a bit of Catch-22 for the districts.

I see three ways through this quagmire:

1) The SIS vendors might figure out that they need to innovate. They must see that their market is demanding something different, right? Currently, they are our biggest barrier to becoming student-centered. From what I can tell, their systems are based on courses or credits (yep, that sneaky old Carnegie unit credit is embedded right into the architecture of the SIS systems). The vendors have tried to adjust by allowing teachers to add standards to courses to support standards-referenced grading. However, it is very difficult, I think nearly impossible, to get information for students to track their own progress, for teachers to be able to group students based on where they on the set of standards, and for principals to keep an eye on pace and progress of students across the school.

Perhaps the districts in Oregon could call together their SIS vendors and ask them for their plans to respond to their needs. If the vendors can’t offer something within the next year, then the districts need to move on to the next option.

2) No one wants a comprehensive IT system more than educators in proficiency-based schools. The difference from traditional schools is that proficiency-based educators need an IT system that provides real-time data to help educators help students learn, not reports solely for accountability at the state and federal level. It’s hard to disagree with wanting to use scarce IT resources to help students learn. Districts that are committed to systemic proficiency-based education could come together to form a consortium strong enough to purchase one of the proficiency-based information systems. The consortium needs to be big enough to be able to negotiate some price reduction and to generate enough political will that the state leadership has to take proficiency education in general, and a proficiency-based IT system specifically, into consideration as they think through a Pre-K/20 system.

3) State leadership could start thinking about what a proficiency-based Pre-K/20 system might look like. (Thanks to Karla Phillips for helping me understand this). It’s not that we don’t value a strong Pre-K/20 system, it’s just that it is wasteful to use resources in traditional, time-based ways when district after district is seeing the value of a comprehensive, personalized, proficiency-based system. This isn’t an either/or decision. By investing in proficiency-based IT systems now, the state can begin to put together the pieces of a statewide proficiency-based Pre-K/20 system. Other steps might include convening districts to help calibrate their standards so that there is a shared understanding of proficiency (this is a big step towards equity so that a student going to one school is expected to learn to the same rigorous standards as students in a neighboring district). They can engage institutions of higher education (IHE) to clarify what exactly readiness for college without remediation looks like and to develop a language to talk about the different standards each IHE uses.

Oregon is often shaping education policy that is ahead of the rest of the country. Right now, they are teetering between two systems. They’ve got many of the pieces in place but haven’t quite taken that step to expect that their schools should be high performing (or high reliability), that is, continuing to teach students until they have mastered the standards and skills. Once they make the decision to go forward with a proficiency-based education system, the early adopter districts will be able to put together a full proficiency-based system, eliminating the trappings of the time-based system that are holding our students and communities back.