Can Competency Education Work in Urban Districts?

CompetencyWorks Blog

I’ve been hearing this question by foundations that are excited about competency education but are focused on investing in solutions for big districts in order to reach the most low-income students. (Interesting that Puerto Rico is the third largest school district and I don’t know of any foundations investing there.) “Urban” can be a code for students and families with brown and black skin that don’t have much in the way of financial assets. For those who need proof points that CBE works for “urban students”, the Barack Obama Charter School in Los Angeles is one. (Read the CompetencyWorks blog about it here.) I believe in this instance, however, the concern about competency education’s workability in urban districts is more about the size of the districts and the difficulty of introducing reforms.

My first advice to foundations that want to support big districts is to expand their boundaries. There has been a demographic shift over the past 20 years, with poverty slipping into inner ring suburbs. Adams 50 is an example of a suburban district at the edges of Denver that decided they had to do something different as they realized that the traditional system was in their way of responding to a changing student population. (Read the CompetencyWorks blog about it here.) Foundations can take advantage of this “opportunity” by investing in the neighboring smaller districts that are trying to find responses to increasing poverty in their communities. Not only will you create a proof point for the surrounding districts, you will also begin to build a cadre of educators that can easily train others or even take on leadership in the large districts.

For large districts and their foundation partners that want to take on competency education right now, here are a couple of ideas about how to get the ball rolling. A note of caution: These are ideas that I’ve pulled together from my own experience and from talking with folks. None of these ideas has been tested or developed in partnership with others. Please, please, please, if you disagree or want to add depth to anything here, leave comments.

How Strong are Your PLCs? If a district is even thinking about competency education, they need to start with checking out the health of their professional learning communities. I haven’t visited any competency education schools that don’t highlight how teachers share student work to build a shared understanding of proficiency, creating common rubrics and assessments, and begin to exchange their tricks of the trade to improve feedback and instruction within the PLCs. Competency education emphasizes the professionalism of teachers and gives them the time (and respect) they need to focus on students, learning and their skills. I’d go as far as to say that if a district was to have an application for schools to become competency-based, one of the big readiness criteria is the strength of their PLCs.

How Autonomous Are Your Schools? We are starting to understand that within competency education, autonomy is as important a concept as transparency. It’s just about impossible to have a high degree of personalization within a school that is being driven by memoranda from above. Schools need a great deal of flexibility and ability to deploy resources around student need. Furthermore, and possibly more importantly, you can’t have student agency (what Jobs for the Future describes as student ownership of learning) unless teachers have agency as well. Without these traits, schools really are asking for a lot of unhappiness and frustration.

Thus, one of the things districts can do is check their own values, approaches and operations to identify where they have shifted agency to the schools or where they are holding it as a district responsibility. Hiring decisions in a competency-based school need to be made by the school, as teachers will be working collaboratively around students and will need strong organizational capacities. Schools also need to manage budgets and the deployment of resources as much as possible.

How to Build the Shared Understanding? One of the big transitions for some schools is from a fixed mindset to a growth mindset and from a bureaucratic culture to a learning culture. Almost every district I’m familiar with that is successfully converting to competency education started with this reading list for school board members, educators, parents and even students:

- Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck

- Inevitable: Mass Customized Learning: Learning in the Age of Empowerment by Charles Schwahn and Beatrice McGarvey

- The Global Achievement Gap by Tony Wagner

- Delivering on the Promise by Richard A. DeLorenzo, et al.

- Building a New Structure for School Leadership by Richard F. Elmore

To Pilot or Not to Pilot: I’ve heard people argue wholeheartedly on both sides of this discussion. Pilots are easier to get off the ground. They are lower risk. They build up some knowledge early on. However, they don’t easily or naturally expand beyond the pilot stage. They are often viewed as suspect, especially if they get extra funding. And in the case of competency education, they may not get desired results if implemented in just a few classrooms because competency education is in fact a schoolwide model.

Some also think that pilots are really good ideas when you know the solution and just want to work through the kinks of implementation. However, when you are in the process of addressing a problem without a technical solution, it is better to create a process that allows the organization to learn. We do know how to convert small and mid-size districts to competency education – it’s one-third technical solution, one-third leadership and one-third exploring how to organize schools so that students succeed.

As big districts think about getting started, they may want to think about a school or a few schools being the pilot. The pilot schools would want to be involved, which means they had spent some time engaging staff around the “why” and the “what” and hopefully the “how”. As described above, they would need to have strong PLCs and they would need a great deal of autonomy. In other words, districts would need to get out of the way and allow them to learn from their mistakes.

Can You Expand the Variety of Schools in Your Portfolio? Some of the large districts have stopped trying to run schools and have started managing a portfolio of schools. These districts are probably well positioned to open up competency-based innovation, as they are already used to having schools operating with a variety of approaches. They could certainly invite schools to become competency-based or start new competency-based schools.

However, portfolio districts need to make sure their left hand knows what the right hand is doing. A few months ago, I visited with educators, community leaders and district staff in Denver about their efforts to innovate. Many were frustrated, because even though they had innovation schools, the models were still looking fairly traditional. It wasn’t so surprising to me; during my visits, I heard stories about district personnel telling schools that they couldn’t have flex hours (an element of just-in-time instructional support) because they needed to have 300 minutes of instruction. This makes me think that any district wanting to support competency education in some of their schools is going to have to do some training with their district team across departments to make sure that they begin to build their schools focusing on learning and competency, not time-bound regulations.

Can We Learn from the States? With a population of 1.3 million and an estimated 270,000 under the age of 18, New Hampshire’s schools are serving a similar number of students as Broward Country, Houston and Clark County. So why can’t we take a page from the leading states in thinking about district-level change strategies?

One strategy that jumps to mind is establishing a proficiency-based diploma. Is there any reason that districts can’t do that even if their states haven’t? The opportunity that develops is that meaning has to be created about what proficiency means. I wouldn’t use Colorado’s policy as it defines proficiency based on a number of exams. Instead, I’d look at the bottom-up/top-down approach in Maine, which was supported by the Reinventing Schools Coalition and the formation of the Maine Cohort for Customized Learning. Imagine if your schools that wanted to be competency-based began to meet together to address issues.

In New Hampshire, we saw districts start out creating their own competency frameworks and then, over time, realizing that the state was better suited to develop the statewide infrastructure of competencies. The New Hampshire Department of Education then created a process so that districts could participate in the creation of the competency frameworks.

It will be more important for districts to have a shared competency framework than within a state because of high mobility of students – portability is going to be essential if students are going to have educational continuity. So districts could design a two-pronged approach that provides supports as schools start to experiment with different ways of thinking about their competency frameworks (and the granularity), what proficiency looks like, and systems of assessments. However, if everyone knows that they are going to have the opportunity to come together they are likely to exchange ideas earlier on. The goal would be to have minimal elements of commonality that allow for portability with maximum levels of autonomy at the school level.

How to Engage Community in a Big District? We know that engaging community to create a shared vision is an important part of competency education. Big districts are much more comfortable with “buy in” models and I’m pretty convinced that this is going to trip them up from the beginning. For communities that have felt betrayed by their school districts over the years, “buy in” feels a lot like “lyin’.” It is almost impossible to create a shared vision that starts with one group already deciding what the solution is going to be. I’m going to emphasize this – districts should not lead with competency education as the solution, community members need to share an understanding problem and an idea of what they want for their kids. It’s actually a great sign if the language of competency education is never mentioned. Lindsay Unified School District has been an exemplar in their process and their sustained focus on designing a system that works for students.

My guess is that converting school by school might make the most sense for big districts with a combination of district and school leadership engaging the community, parents and employers. It may seem like a lot more work in the beginning but it’s also laying the groundwork for sustainability. Certainly, if there are any relational community organizing groups operating in the neighborhoods I’d also engage them as their leadership models are highly consistent with the mutual accountability models that develop in competency education.

What Not to Do. Bottom line: Competency education cannot be implemented by memo. If you place the competency education structure on top of a school that does not have a majority of teachers sharing a growth mindset you are going to get linear, worksheet-driven, oh-so-boring classrooms with the same results of some students being passed on without the skills they need. Competency education really is a bottom-up strategy where educators move beyond their frustration of not being able to help more kids and demand a way of operating the school that really works for their students.

District staff are used to trying to figure out all the details of a program and then pushing it out through RFPs, regulations, and memo. That won’t work here. It’s best if district staff do the homework to make it easier for school staff to learn about different approaches. Instead of trying to figure out the best way, district staff can identify options and the implications, pros and cons, risks and benefits. Schools need to have as much autonomy as possible to make decisions that fit into their overall design and implementation strategy.

This can leave district staff wondering, what is my job then? They like other educators involved in converting to competency education will need to be developing their leadership skills to listen to others to identify problems, engage others in solving problems, and participating internally to re-design a district system that supports schools that are supporting teachers that are supporting students.

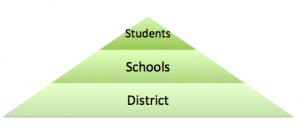

Try inverting the organizational chart so that students are the focus of everyone’s efforts.