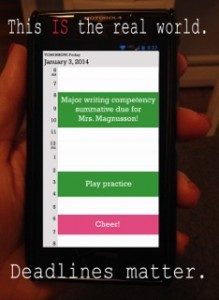

Deadlines Matter: Debunking the Myth That Standards-Based Grading Means No Deadlines

CompetencyWorks Blog

I have a very compassionate boss. I spent several weeks working on my school’s budget for the upcoming year and I had been sending her updates on my progress throughout. It shouldn’t have come as a surprise to me, though, that on the week that the budget was due my high school had a series of unexpected student issues that consumed most of my time and resources. As important as that budget due date was, I knew I just wasn’t going to make the deadline. As much as I hated to admit defeat, I made the call to her on Friday afternoon to ask for an extension (or at the very least, forgiveness). She was quick to respond to me with this: “Brian, I know it has been a tough week for you. I know through our check-in meetings over the past few weeks that you have been actively working on it. It is ok if you need a little bit more time. Could you have it to me by the middle of next week?” As she uttered those words I could feel the weight of the world lifting off of my shoulders. “Of course I could, thank you for your flexibility!”

What happened between my boss and I that day happens in all aspects of our lives as adults. It is normal behavior to expect that every once in a while people are going to miss a deadline. In the classroom, we as teachers know that students will miss deadlines from time to time. When they do, we do what any normal teacher would do—we become compassionate and flexible. Just like in real life with adults, we only start to worry about the behavior of missing deadlines when it goes from once in a while to chronic.

In the real world the chronic misbehavior of missing deadlines is rarely tolerated. People can lose jobs over too many missed deadlines. They can miss out on first-come-first-serve situations where demand exceeds supply like those popular concert tickets that went on sale at noon and are gone within the hour. What about students? When I was a teacher ten years ago my students lost the ability to get the best possible grade when they missed a deadline. I was a big fan of policies such as ten points off for each day late or if you don’t do the work you will have to take a zero on the assignment and suffer the consequences. I was always shocked to have students who would take the time to calculate which assignments they could afford to take a low grade on by not doing (or doing late) and still get the final course average they were hoping for, until I realized that I did the same thing when I was a student.

Winger (2009) described this scenario as an unintended consequence of a broken traditional grading model—a model in which “students received so much credit for completing work, meeting deadlines, and following through with responsibilities that these factors could lift a student’s semester grade to a B or an A, even as other indicators suggested that the student had learned little.” That grading system wasn’t fair to me when I was a student, and it isn’t fair to students who live with it today. Wormeli (2006) argues, “a grade represents a clear and accurate indicator of what a student knows and is able to do—mastery.” Deadlines are important, but if we factor in the behavior of turning an assignment in on time or not into an overall assignment grade, then we are watering down our whole grading system.

My school, like many across the country, has abandoned traditional grading and reporting for a competency-based approach. In such a model, traditional grades have changed for the better. Academic grades are separated from academic behaviors like meeting deadlines, participating in class, and leaving perfect margins. No longer do teachers combine academic indicators of what students have learned with academic behaviors like a big pot of beef stew that just blends everything together into a monotone flavor. Competency-based schools report out on the level of mastery students achieve for each and every course competency, as well as their mastery of key academic behaviors.

The problem my school has had to face, like many schools who move to this model, is how to make sure that the academic behaviors like meeting deadlines stay relevant and meaningful for students. There is a big myth in education that if you move your school to a competency-based model then students won’t see the importance of deadlines and you will hence have a higher-than-normal rate of students not completing work on time. I am here to tell you from experience that this myth can be true or false and it depends on two important factors:

1.Teachers need to be effective at changing their instructional practices and their approach to working with students on the behavior of meeting deadlines.

I have compiled the following summary of instructional practices from conversations with teachers in my school who have had the highest success rate over the past three years in getting their students to regularly adhere to deadlines:

- They often adopt a take no prisoners approach at the beginning of the school year when it comes to working with students who miss a deadline. They instill a belief in students that no one is going to let them out of doing the work, and they can avoid harassment by adults if they simply turn things in on time.

- They build in multiple opportunities to check in with students on their progress on major summative assignments. If they aren’t making the progress they should be making to meet a deadline, they take steps to resolve it right away.

- They start parent communication as soon as a student misses a deadline. Many have told me that a simple phone call home often results in getting the work the very next day.

- They assign the student mandatory time with them to work on the assignment outside of the classroom – either in a study hall, flex period, or before or after school. This practice is supported by O’Connor (2009).

- They let students know that if they do not turn in an assignment on the due date, then the student may be held to a different rubric with higher expectations. Wormeli (2006) endorses this practice, encouraging teachers to “reserve the right to change the format for all redone work and assignments”. It stands to reason that as time passes during a school year students acquire more course-specific skills and knowledge and therefore can be held to a higher standard in all of their work for that course.

2. The school needs to have an effective system in place to monitor and communicate academic behaviors, thus holding students accountable for their behavior.

In our school-wide system, meeting a deadline is a behavior expectation just like any other school rule. Following the suggestions of Guskey (2009), our school does not punish academic student misbehavior with low grades, but rather motivates students by considering their work as incomplete and then requiring additional effort. As a school, we address this student academic misbehavior through a tiered approach that operates like this:

- First the teacher will try to address the misbehavior at the classroom level with the student.

- If that doesn’t work, the teacher may involve other adults from the school that know the student (counselors, case managers, or a team leader) in the conversation with the student.

- If that doesn’t work, the teacher will involve the parent or guardian in the conversation.

- Finally, if all else fails, the teacher will make a behavior referral to an administrator for additional support. The administrator will then work through a series of actions in an effort to address the misbehavior.

- The student grade will be marked as IWS, which stands for insufficient work shown, while the issue is addressed. IWS grades that are not resolved by the end of a course result in a course failure and no credit for the course.

Is the system in place at my school designed to address misbehavior perfectly? It is far from it. On a regular basis we look at the types of misbehaviors our students engage in and we make adjustments to our system to more effectively manage those behaviors. We are constantly developing how we use this system. I expect we will continue to do this until the day comes when we don’t have any student misbehaviors. The key to this approach is that we have identified academic behaviors as a school-wide issue with common expectations for student behavior and developed responses—as a school—when they don’t meet those expectations.

The argument that deadlines become lost in a competency-based grading and reporting system is, in my opinion, a moot point. I argue that this perspective needs to be turned around and educators need to ask this question: “When my school moves to a competency-based model, what will I do to ensure that students meet all the expectations, both academic and behavioral, that I set for them?” Hold your students accountable for high standards and don’t let them off the hook for missing too many deadlines. They will thank you later in life.

__

REFERENCES:

Guskey, T. (2009). Practical Solutions for Serious Problems in Standards-Based Grading. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

O’Connor, K. (2009). How to Grade for Learning, Third Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Winger, T. (2009). Grading what Matters. Educational Leadership, 67(3), 73-75.

Wormeli, R. (2006). Fair Isn’t Always Equal: Assessing & Grading in the Differentiated Classroom. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Brian M. Stack is the National Association of Secondary School Principals 2017 New Hampshire Secondary School Principal of the Year. He is Principal of Sanborn Regional High School in Kingston, NH, an author for Solution Tree, and also serves as an expert for Understood.org, a division of the National Center for Learning Disabilities in Washington, DC. He lives with his wife Erica and his five children Brady, Cameron, Liam, Owen, and Zoey on the New Hampshire seacoast. You can follow Brian on Twitter @bstackbu or visit his blog.