Debunking a Myth – Competency-Based Transcripts Don’t Disadvantage High School Graduates in the Admissions Process

CompetencyWorks Blog

A transition to a competency-based education system brings with it many small and large changes. In order to serve their students better, districts, schools, and teachers change instructional practices, strategies, feedback, and, frequently, reporting. These changes are made in order to more accurately capture what a student knows and is able to do – how they are performing in relation to rigorous, common, shared expectations. While all of these changes should be made in consultation and collaboration with school communities, in response to the vision that they have for graduates, some of these changes are more visible to them than others. Transcripts represent one of the most visible – and public – of these changes.

A transition to a competency-based education system brings with it many small and large changes. In order to serve their students better, districts, schools, and teachers change instructional practices, strategies, feedback, and, frequently, reporting. These changes are made in order to more accurately capture what a student knows and is able to do – how they are performing in relation to rigorous, common, shared expectations. While all of these changes should be made in consultation and collaboration with school communities, in response to the vision that they have for graduates, some of these changes are more visible to them than others. Transcripts represent one of the most visible – and public – of these changes.

The ultimate goal of our system is to graduate students who are college and career ready and prepared for the futures of their choosing. Admission to a college and university is a huge part of that future for many of our graduates, and it is only natural that students and parents will immediately think about the implications that the shift to competency-based education has on college admissions. These concerns can be particularly acute for parents who were served well by more traditional educational systems and those whose students have historically thrived in such conventional academic settings.

The Great Schools Partnership and the New England Secondary School Consortium (NESSC) have worked to address these concerns in a variety of ways. The engagement began by working, over the course of a year, with deans and directors of admission, high school guidance counselors, and principals to create a sample competency-based transcript that would serve as a model for secondary schools to use, change, and adapt to their local context with the assurance that it met the needs of a variety of admissions officials. At the conclusion of this process, the group of deans and directors of admissions requested to continue working together to create a sample school profile, knowing just how critical a clear, complete, brief, easily understandable school profile is in the admissions process. The school profile conveys important descriptive information about the school, its academic program, and its community, and they are customarily included in student applications to colleges and postsecondary programs. The school profile is especially important for admissions staff with fewer resources and limited internal capacity.

Following that process, the NESSC transitioned to gathering a repository of letters from public and private colleges and universities that unequivocally state that students from competency-based systems are not disadvantaged in the admissions process. To date, the NESSC has collected statements from seventy private and public institutions of higher education across New England (including Harvard, Dartmouth, MIT, Tufts, and Bowdoin). These efforts are ongoing and additional statements will be added and are available for download on the NESSC website.

Additional resources about engaging with your community around these questions (and an interview with Nancy David Griffin, Vice President for Enrollment Management and Student Affairs at the University of Southern Maine) can be found here.

Questions about competency-based learning and college admissions are not context specific. They are at least a consideration in every district implementing competency-based learning. In every community, there are students, parents, teachers, and community members who would like to better understand the ways in which this transition impacts the college admissions process. These questions recognize that there are serious flaws with traditional educational systems: the assumption that traditional grades are equivalent school to school and classroom-to-classroom is false. The assumption that earning a high school diploma means that a student is prepared for college coursework and experiences is false, proven wrong by the high rates of remedial course taking across the country.

Competency-based education tackles those inconsistencies by being much more explicit about clear, common, rigorous expectations for all students and then reporting student progress toward those expectations in student transcripts. Building on our previous work and resources, in order to even better understand how those shifts were translating in the college admissions process, the New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE) and the New England Secondary School Consortium, longtime partners, decided to join forces once again to host a focus group and gather more detailed information from deans and directors of admissions.

In January of 2016, the focus group, with deans and directors of admission from exclusive private colleges and universities in New England, was held to better understand the ways in which they evaluate student transcripts and profiles, their experience with applications from competency-based systems, and best practices for school transcripts and profiles. The New England Board of Higher Education prepared and published a white paper, “How Selective Colleges and Universities Evaluate Proficiency-Based High School Transcripts: Insights for Students and Schools”, which captures a summary and findings from the gathering.

The gathered deans and directors of admission from the most selective private institutions in New England provided a resounding, loud, powerful message that students from a competency-based system are not and would not be disadvantaged in the admissions process. The deans and directors of admission at the focus group wanted students, parents, teachers, schools, and communities to understand that they review applications holistically, working to understand each student in their unique context, looking at the breadth and depth of their experiences. They stressed that they evaluate thousands of candidates each year from all over the world, and the transcripts, school profiles, and systems they see differ drastically.

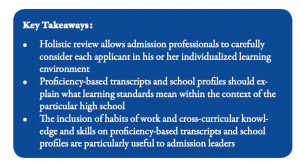

Beyond that particularly important statement, additional focus findings include:

While the deans and directors of admission that NEBHE and NESSC met with stressed that they examine and determine how to evaluate candidates with many different transcripts, there were specific elements of the transcript and profile that enable them to make determinations with particular ease. They saw these elements in the Great Schools Partnership sample transcript:

- Specific (and clearly represented) explanation of what a student knows and is able to do – this is in stark contrast to what has traditionally been shared on a report card

- Clarity of the information provided (admissions personnel wouldn’t have to hunt for information; detail, length, and presentation of the school profile providing additional clarity around the standards, opportunities to show distinction, elements of the competency-based system, etc.)

- Clear presentation of student’s progress on the Guiding Principles (or Transferable Skills, 21st Century Skills, Cross-Curricular Skills, etc.). These stood out to deans and directors of admission as particularly helpful (in contrast to information they see on many transcripts from traditional systems) and helped them to differentiate the students who had the skills to make an impact on campus – in all aspects of campus life – from their first day

- Habits-of-work captured separately from knowledge and skill

- Learning experiences and demonstration of performance against standards

- Opportunities for students to show distinction (depicted on the Great Schools Partnership sample as outside of the classroom learning experiences and the Latin honors system – which honors the spirit of competency-based learning by setting high bars and capturing every student who meets those expectations)

- A school profile that is no longer than a page (double-sided) and includes details about your competency-based system (clarity around your local expectations aligned to state standards, describing opportunities for students to show distinction, in addition to details about the graduating class)

Changing the status quo can be frightening – for those who have benefited from the status quo and for those who have not. Inevitably questions will arise during a shift to competency-based education about how that shift will be interpreted by the organizations and institutions that receive high school graduates. By including the community in every aspect of conceiving of and designing your system, adapting and building off of systems and supports that already exist, and broadly sharing resources like the collegiate statements, the NEBHE white paper, and the interview with Nancy Davis Griffin, you will be prepared to answer any questions that might arise from your school community.

See also:

- Harvard and Wellesley and Tufts, Oh My! (And Did I Mention MIT and Babson?)

- Performance-Based Assessment in Action

- Red Flag: Converting 1-4 to 100 Point Scale and then Averaging

Sarah Linet is the policy specialist at the Great Schools Partnership. She works with internal and external partners and stakeholders to advance the mission of the New England Secondary Schools Consortium to close achievement gaps and promote educational equity and opportunity for all students through federal, state, and local policy.

Stafford Peat is a senior consultant at the New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE). He is a member of the NEBHE Policy and Research team and supports states in adopting high-impact higher education policies and evidenced-based practices to increase the region’s competitiveness.