How Competencies Influence Teacher Practice

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second post in a series by Tommy Wolfe about the findings from his doctoral research. Links to the other posts in the series are at the end of this article.

Competencies are a model for learning objectives that are intended to expand the definition of academic success and encourage students to authentically apply their knowledge. My research found that using competencies helped teachers sharpen their practice, teach skills (in addition to academic knowledge), align their teaching with enduring educational aims, and facilitate and differentiate learning.

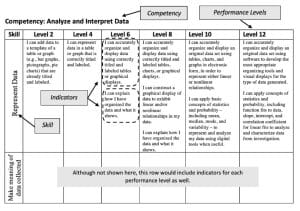

Competencies differ from standards in many important ways—even from a typical standards-based 4-3-2-1 scale. Competencies are skill-based, transdisciplinary, and are gradated along a continuum. A simplified example of the competency Analyze and Interpret Data is shown in the figure below. When the terms “skill,” “indicator,” and “performance level” are used in this blog post, they are referencing how those terms are used in the figure.

To understand how teachers use competencies and how they influence their practice, I interviewed multiple teachers who were teaching at competency-based high schools. In this blog post I share many of the interesting findings that emerged from these conversations.

Honing Practice

Every teacher I interviewed shared how competencies had sharpened their practice. A teacher who had previously taught 17 years before using competencies described her experience over the past five years of teaching with competencies:

“It’s been amazing. It’s been transformative. I wish I would have been able to teach with competencies my whole career…They make it really clear as to what skills matter, what skills to focus on, how to help students understand where they are excelling, and where they need to go. It hones your practice…you’re not going to get by with worksheets. It ups the ante for teaching.”

The competencies were not just an assessment tool, they were a design tool as well. Teachers would use the indicators for competencies as their learning targets when planning a unit. A teacher shared her thinking when lesson planning: “Am I actually accomplishing this skill? Let me see [the indicators]. You have to be really critical of all your lessons because it has to be aligned to a skill.”

Learning to Teach Skills

Because competencies dictated how performance was assessed at the schools under study, naturally more attention was given to teaching the skills that comprised each competency. One teacher shared, “If I was in a more traditional model, it would be a lot more challenging for me [to address skills]…whereas it’s literally built in our school for the students.”

Teaching skills required a mindset shift for teachers. For instance, a science teacher shared:

“[Early on] I would teach them the content and then just randomly give them the competencies…Now this past year, we finally had a breakthrough where we are finally starting to teach the competencies, and we are using the content like a guide to teach the competencies.”

Enduring Understandings and Aims

Teachers consistently demonstrated a strong commitment to the enduring understandings that they aimed for students to develop from their course. For instance, many teachers shared the deliberate aim of empowering their students with agency in authentic contexts. Teachers also consistently aimed for enduring understandings related to their particular discipline—such as students in a science class learning to make ecologically aware decisions.

These enduring understandings and aims drove curriculum design, and competencies followed from there. For instance, one teacher said,

“The competencies are great, but what do I really want to teach these kids? Once you figure that out, then you’re like, ‘Alright what are the best types of projects that would allow me to get that across?’ Once you do that then, you’re like ‘Okay, let me look at the competencies. How can I fit the competencies into the project?’”

Competency-based education seeks to profoundly change how students learn, and although the structures that can support it such as competencies are important, it is also vital to be cognizant of the greater enduring understandings and aims we want students to get from an education. I admired how the teachers prioritized these aims and how they utilized the competencies to support them.

Using the Competencies to Facilitate

Many teachers saw their role as that of a facilitator rather than a deliverer of knowledge. “You are there to empower kids, not to tell them what to do,” one science teacher shared. A school leader shared:

“[Using the competencies] forces you to focus most if not all your time on giving feedback to kids to revise their work. The teachers that have been with us the longest have completely changed their practice. To go really deep on less content and do lots of revision cycles.”

Many teachers emphasized the importance of students doing rather than teachers delivering. “I have 50-minute classes. Five minutes is actually me talking to the whole group. And the rest is small [groups],” one teacher explained.

To support their roles as facilitators, many teachers developed multiple resources for students to take greater ownership of their learning, which I called scaffolds for agency. For instance:

- Teachers created unit guides that typically were websites that provided all the expectations and resources for a particular project or unit.

- Teachers created performance task guides that acted like a mini-book for students to see detailed instructions on how to perform the skills of a particular competency. (These were typically presentation slides or part of their website.)

- Within the performance task guides, teachers also provided exemplars for students to see what a final product may look like.

- The competencies themselves were a scaffold for agency as students could use them to see what indicators they needed to accomplish to effectively demonstrate a competency.

These scaffolds for agency have significantly influenced my teaching practice and I will elaborate more on these in my third blog post.

The scaffolds for agency took considerable time for teachers to create, but once made, the Performance Task Guides and Exemplars could be repeated from unit to unit. Speaking about the amount of prep work required, a science teacher explained, “the workload is a lot, but it also isn’t—because [all of my classes] use the [same] competencies.” In addition, because competencies are transdisciplinary, teachers supported each other by building a collective library of resources that all disciplines could use.

Meeting Students Where They Are

Teachers also discussed how the competencies allowed them to differentiate learning for their students. They stressed how the competencies allowed students to work towards the same skill, but at their own individualized performance levels.

Competencies provided a roadmap for students to grow. One teacher described how the competencies helped with the daunting task of guiding students that needed to move up multiple performance levels:

“The thing I love about competencies is they give students the ability to build. They feel like they are achieving something. They move up a couple of levels and see themselves improve. It’s more of a stepper.”

Competencies also helped with enrichment. One teacher said:

“We’ve all had tons of kids that come into the class already at grade level, and [for a teacher] in the conventional system it’s like…‘my job is done here.’ With competencies, there is never a limit. [There isn’t that mindset] that the student just gave me a 100%, so I’m done. You can always get better.”

Although the competencies appeared to provide advantages for differentiation, one teacher effectively managing this for all students within a class remained a challenge. School leaders discussed how differentiation was needed at the school-wide level to enable educators to better coordinate the supports and flexible pacing each student requires.

As shown above, the competencies appeared to provide a useful structure for teachers to sharpen their instruction, emphasize skills, prioritize enduring understandings and aims, facilitate learning, and differentiate learning. These findings may prove helpful in navigating competency-based curriculum design and advancing teacher practice.

Learn More

- Competencies Help Bridge the Gap Between Traditional and Project-based Learning

- Scaffolds for Student Agency

- Teacher Insights on Developing Competency-Based Practices in the Classroom

Tommy Wolfe is a high school science teacher at Adlai E. Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, IL and is an Adjunct Professor acting as the Competency-Based Lead for DePaul University’s Office of Innovative Professional Learning in Chicago, IL. He holds a B.S. in Integrative Biology, a B.S. in Psychology, an M.Ed in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign and a Ph.D in Educational Leadership from DePaul University.

Tommy Wolfe is a high school science teacher at Adlai E. Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, IL and is an Adjunct Professor acting as the Competency-Based Lead for DePaul University’s Office of Innovative Professional Learning in Chicago, IL. He holds a B.S. in Integrative Biology, a B.S. in Psychology, an M.Ed in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign and a Ph.D in Educational Leadership from DePaul University.