How Standards-Based Grading Led Us to Empower, Part 1: The Tyranny of 82%

CompetencyWorks Blog

Increased interest in student-centered learning management systems that support equitable assessment and student self-direction as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic further amplify the value of this excellent two-part series that was originally posted on the Edtech Elixirs blog. Adam Watson is Digital Learning Coordinator for Shelby County in Kentucky, a district that’s deeply devoted to competency-based education.

I have often talked in Edtech Elixirs about how digital tools should help us serve an academic objective. For our district, the need for effective standards-based grading (SBG) began a search for a transformative digital tool. In this blog entry—the first of a two part series—I discuss how the limitations of a traditional grading system led us to SBG, and ultimately, Empower Learning.

I’d like to start this entry with what I like to call “the tyranny of 82%.” While it’s fictionalized, it’s based on the reality I have faced in the past as a classroom teacher in a traditional grading system.

A parent walks into a classroom to discuss her son’s current grade with his English teacher. “I’m worried,” the parent frets. “Timmy currently has a 82%. That’s a B. A low B. What can he do to raise it to an A?”

“I’d be happy to help,” the teacher smiles. “I have some practical advice for him. He should work 8% harder.”

“But…how?” the parent asks.

“Well, let’s say right now he studies 50 minutes a week. Timmy should start studying 54 minutes a week. That’s eight percent more effort.”

“Oh yes. I get it now. Anything else?”

“Yes. He should always get a high grade on every assignment, right from the start. Let me give you an example. Last week we started a new unit on a concept he had never done before. He got a 20 out of 100 points on the first big assessment. At the end of the unit, he aced a final assessment with 100 out of 100 points. But it was too little too late. All that effort at the end and he only got an average of 60 percent in summative assessments. Of course, if it makes you feel any better, Timmy could have gotten a 100 on the first assessment and 20 on the last one and would have gotten the same grade overall. He should have scored high all along, you see? The math of averaging doesn’t lie. And I average all students, all the time. It’s only fair!”

“Ahhh! Very fair. Thank you for the practical advice!”

Of course, the above is farcical. But as a classroom teacher analyzing an overall course average in a traditional grading system, I wish I could have given feedback to a student or parent as confidently as the fictional teacher above. On a good day, I could have pointed to a well-designed rubric for a particular assignment to show how you could improve from good to great, but therein lies the problem—a rubric helps explain the score on a particular assignment, and not really an overall course grade. For a typical student that wants to increase their class grade by a level or two, I would usually fluster through a conversation on points—if only they had gotten a bit higher on this quiz or that project, or would get full points on an assignment next week, their grade would go up. For failing students, it would be a much easier conversation, since it was often a problem of zeroes, and therefore the talk was about completion and compliance. If Timmy had just turned in a few more of his homework assignments and that big paper from last week, he might not have a F!

If all this talk of points makes school with traditional grading sound like a game to either win or lose, it often is, and therefore no teacher should be surprised when students try to manipulate such a high-stakes and highly subjective system. (Don’t even get me started on how “extra credit” skews the validity of academic data even further, or how enough zeroes can create a statistical hole that even the most motivated student would not be able to climb out of.) However, the problem in all of this talk of points and completion and compliance is the absence of what should be the true question to consider: how does 82% reflect what Timmy actually knows in English?

The answer: it doesn’t.

Percentages aren’t always impractical, of course. If I have a 82% approval rating, there was a poll result that revealed 82 out of 100 people like me. If a medical procedure has a 82% success rate, I can take comfort in the fact that there are “only” 18 out of 100 case studies when the procedure fails. But if someone said that I am 82% in my husband skills, or a podiatrist is 82% in his medical knowledge, we would laugh at the absurdity of how non-informative those percentages are for such broad concepts. Yet no eyelids are blinked when a percentage is applied to an entire course and we say a student is 82% in English, or Geometry, or Physics, or U.S. History.

We should note something about letter grades before we move on. An A-B-C-D-F system is not in and of itself necessarily bad—I would rather deal with a five-point-range system than the hundred-point-range system of percentages—but what is troubling is often the vague understanding and frequent inconsistency of what a letter grade means. For most traditional grading systems, the letter grade is simply the mask that a school or district’s percentage wears at the ballroom school dance of public opinion, in an attempt to feign academic consistency and conformity.

To take the simplest example of how this mask conceals more than it reveals, consider that even the scale used to translate a percentage into a letter grade can vary district to district in the same state, or even school to school in the same district. An 80-89.9% could be a “B” in one location and 86-92.9% could be a “B” in another. So, again: How does a “B” reflect what Timmy actually knows in English?

If we take it as a given that a game of percentages is not the best system of grading—and many of you were likely nodding your head about that way before this point in the blog entry!—what could replace it? First, we need to start with the question that Ken O’Connor poses in the short video (2:36) below: “How confident are you that the grades your students receive are consistent, accurate, meaningful, and supportive of learning?” If we are not confident in the system we have, let’s find a better one. To paraphrase from O’Connor’s video, if students are “playing the game of school,” let us at least make sure it is a learning game and not a grading game.

It was the pursuit of a more effective grading system that led Shelby several years ago to begin a transition to standards-based grading (SBG). While all teachers have theoretically planned instruction around their state standards for many years, SBG looks at measuring student academic progress through the lens of how they are doing in each standard that is pertinent to a particular class. As we explained in a recent handout to parents, “Course standards should answer the question: What is it we want our students to know and be able to do?”

In order to articulate where a student is currently in their standards in as clear and consistent way as possible, we have created mastery scales (whole numbers from zero to 4) to go with these standards. These scales work macro and micro: not only are they used to assess a specific task or evidence of learning with a score of 0 to 4 in that standard, the same scale applies to the overall standard when assessing the student’s body of evidence. Effective SBG practice is an important step on the journey to mastery learning—when students can clearly and meaningfully apply their knowledge in new contexts—and, eventually, a true competency-based education (CBE) system. Our current Shelby Strategic Leadership Plan 2.0 has a goal of a CBE system by 2022. (For a good starting place on learning more about competency-based education—in particular, a new updated definition of CBE—I highly recommend checking out the Aurora Institute’s new paper released in November 2019.)

When a teacher does SBG well (after support, experience, and practice), SBG is clearly much better at meeting O’Connor’s four characteristics of effective grading. Let’s look back at the 82% conundrum. If the reporting instead indicated how well Timmy was doing in his English standards (rather than the accumulated or averaged points from a gaggle of assignments), areas of strength and challenge would be much more clear. We can not only see Timmy’s success in standards with a 3 or 4 overall score, but we can quickly focus on Timmy’s potential struggles in standards with a 1 or 2 score. By reviewing mastery scale language, we can determine what it would take to improve in those struggle areas.

So let’s use O’Connor’s language—”consistent, accurate, meaningful, and supportive”—to evaluate SBG: the common mastery scales keep us accurate and consistent across teachers and schools. Discussing overall standard scores is a much more meaningful way of answering “How is Timmy doing?” than a vague overall course percentage or letter can achieve. And student learning is supported when the scores on standards can lead to clear action steps of improvement.

The philosophy of SBG is not the stumbling block for most educators. When explained like I did above, who would argue that the traditional grading system is more fair than SBG? The issue is in the application—how to track and monitor SBG, especially over time. While some teachers have accomplished this without digital help, it is time-consuming and difficult. You can “hack” traditional online student information systems (SIS) to attempt SBG, but such tools are often teacher-centered and optimized for linear assignment record-keeping.

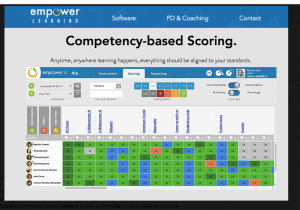

A few years ago in Shelby, our teachers asked for something better—not only in an online gradebook, but in a learning management system (LMS) that had SBG as its centerpiece. After a committee of teachers and admin reviewed several platforms, Empower Learning emerged as the most comprehensive digital tool for several reasons.

First, it is student-centered. Not only does it allow for better student advocacy of seeing their academic performance in all classes over years of their academic journey, it allows all of the student’s teachers to see all of his/her academic performance in all areas. (Imagine trying to make an advisory system without such a transparent system of support!) Compare this to a teacher-centered student information system that is built to record assignment completion and is silo’d to begin and end information for mainly just that teacher, for just that class, for just that school year.

Second, it facilitates doing personalized learning well and can help a teacher use their time more effectively. Without academic information to keep it rigorous, personalized learning could potentially become all voice and choice without rigor and equity. Personalized learning is best when both the teacher and the student can easily see areas of mastery (if you have mastered all fourth grade standards, why not begin on the fifth grade ones?) as well as standards with low scores requiring intervention. Personalized learning can also be time-consuming to plan and facilitate for a teacher, so digital tools to help streamline this are important.

Third, behind an overall standard score, you can see the historical body of evidence that led to that score. I’ve seen gradebooks in other systems where the standard score may have changed from 2 to 4 to 3 over several school weeks, yet it is not clear why or how the score changed. Instead of a real-time story, you can only see what the standard score is right now—or, at best, 3 or 4 “snapshots” at the end of quarterly terms. As a classroom teacher, I patted myself on the back when I made assignments that were standards-referenced (i.e., merely tagged to a standard), but I did a poor job of analyzing how those assignments could lead to a determination of mastery of any particular standard. In both of these cases, it is extremely difficult to improve on these limitations without a digital tool like Empower.

Empower is a “one-stop shop” of LMS needs. While we found some tools that were decent digital gradebooks, few were able to offer the ability to do what a typical learning management system like Schoology, Google Classroom, Edmodo, etc. can do, such as creating quizzes, assigning work for student submission, and housing a collection of resources. Of course, the opposite is also true—for example, Google Classroom offers no gradebook beyond one with traditional points and percentages. Empower organizes both instruction and scoring under one roof.

For more information about the Scoring part of the Empower LMS, visit here.

As we wrap up this entry, I want to return to Ken O’Connor’s video from earlier. He points out that in a truly effective grading system, a student should not ask “What can I do to improve my grade?” but rather “What can I do to improve my learning?” Part Two of this article will go a bit deeper into how Empower integrates standards-based grading and is an important tool to help us make the shift.

Learn More

- How Standards-Based Grading Led Us to Empower, Part 2: The Power of Evidence

- Building 21’s Open Competencies, Rubrics, and Professional Development Activities

- Essential Components of Local Assessment Systems for Personalized, Proficiency-Based Learning

Adam Watson has been an educator in Kentucky since 2005. He began as a high school English teacher, eventually becoming Teacher of the Year at South Oldham High School in 2009 and getting Nationally Board Certified in 2013. Adam was hired in 2014 by Shelby County Public Schools to help lead their 1:1 initiative, and is currently their Digital Learning Coordinator. He is a frequent professional development presenter and session leader at conferences and institutions in Kentucky and beyond. In 2019, Adam was awarded KySTE Outstanding Leader of the Year.

Adam Watson has been an educator in Kentucky since 2005. He began as a high school English teacher, eventually becoming Teacher of the Year at South Oldham High School in 2009 and getting Nationally Board Certified in 2013. Adam was hired in 2014 by Shelby County Public Schools to help lead their 1:1 initiative, and is currently their Digital Learning Coordinator. He is a frequent professional development presenter and session leader at conferences and institutions in Kentucky and beyond. In 2019, Adam was awarded KySTE Outstanding Leader of the Year.