Building 21’s Open Competencies, Rubrics, and Professional Development Activities

CompetencyWorks Blog

At Building 21, we have created an open resource called Learning What Matters (LWM) Competency Framework which includes all of our competencies and corresponding rubrics, which we call “continua.” Every year at the Aurora Institute Symposium, we facilitate a workshop introducing participants to our competency-based model. This workshop is great for folks new to competency-based education (CBE) but it’s also valuable for experienced CBE practitioners who want to learn more about our approach.

A common question we get from beginners is, “but what does it look like?” One of the ways to begin to answer this question is to show participants what grading looks like in a competency-based model and how it is different from traditional grading.

In our workshop, participants assume the role of a teacher, as we challenge traditional grading practices, followed by a demonstration of how Building 21 uses the LWM Competency Framework to change instruction and assessment in its schools. This workshop features the same activities we use with new teachers at our schools. We encourage all schools to facilitate these activities with their teachers even if they are not using the LWM competency framework.

Activity #1 – What Are My Assumptions About Grading?

We start the workshop by asking for volunteers for a mystery activity. Once secured and without telling them what they are volunteering for, we send them out of the room. The remaining participants are given the following set of instructions:

“Each volunteer will come into the room and dribble the ball for 15 seconds. When they are done, you will grade their dribbling on an online form.”

Similarly, in the hallway, volunteers are told:

“You will enter the room and dribble the ball for 15 seconds. When you are finished, the participants, who remain in the room, will grade your dribbling.”

You can imagine that those instructions are inadequate for many people. We almost always get followup questions from both groups about grading criteria, grading scale, or location of the dribbling. And we purposefully do not answer those questions.

Coincidently, we usually have a basketball coach in the grading group. Also, the volunteers typically have a novice dribbler and a former/current basketball player. Upon completion of the dribbling and online grading, as a group, we scroll through a spreadsheet of the grading form responses while participants look for patterns in the data.

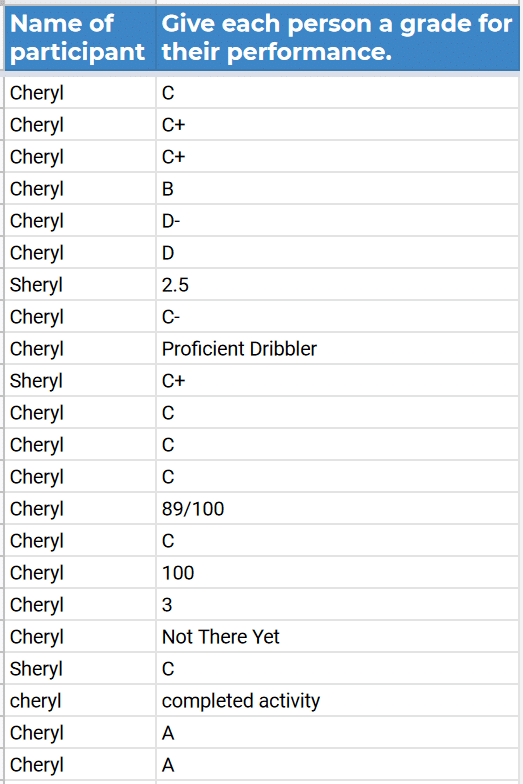

The table to the right shows a typical result for a single dribbler:

The table to the right shows a typical result for a single dribbler:

We ask, “When you look at this data, what do you wonder?”

In the discussion that follows, the group considers the following issues:

- The incredible variability between graders, who are all viewing the same performance

- The diverse grading methods

- The lack of feedback to help the dribbler improve

Additionally, graders share feedback such as noticing that their “standards” changed as they saw more dribblers, and they wanted to go back and re-grade dribblers.

- Sometimes dribblers share that as they saw their grade, they had an emotional response to the low grades.

- There is usually a comment that goes something like this: “The dribbler was told to dribble for 15 seconds, and they all did that, so how can I give them anything less than an A?”

- Graders wanted standardized rubrics shared across graders to limit variability.

This raises some really important questions for the group. What is the purpose of grading? Who is the grade for? What SHOULD be the purpose of grading. What is the value of an F? Is a D good enough for credit? Are low grades motivating?

As facilitators, we close this activity by posing a question to the group that guides our own professional work: “What if you can create a framework for student assessment where the purpose of any grade or rating is to give specific feedback to help the student improve and to measure their growth over time?”

Activity #2 – What Is A Continuum?

We transition to the second activity by challenging the group to create a rubric to address the issues found in the dribbling activity. The participants are given a blank grid with unlimited columns and rows. The only instruction they are given is to place the performance levels across the top and the skills/standards along the far left. Invariably, almost everyone creates a similar looking rubric with four performance levels. The lowest level often contains language like, “Student did not…”

We challenge these almost universal characteristics by asking:

- Does that 4-level rubric work for all dribblers at all levels?

- If not, then do you need multiple rubrics? How many? One per grade level?

- How do you measure long-term growth of skills if there are many rubrics?

- Who are the rubrics written for? For teachers to grade students? Or for students to know how to get to the next level?

- Should the language for each performance level describe what a student should do to meet that performance level or what a student didn’t do?

- Is it more helpful for students to see language about what they failed to do or language that describes what they need to do.

And most importantly:

- If you create a rubric that places a novice at the lowest level, what happens to that student’s data in a traditional tracking system?

We believe this is one of the ways traditional grading is punitive. We punish students for new or unfinished learning because low scores on a rubric are often converted into low traditional grades. Also, these scores typically remain part of the gradebook and are averaged together, lowering the grade and obfuscating growth that has occurred.

At Building 21, we wrestled with these issues and created a framework where the assessment and feedback system is designed to be student-centered, transparent, and focused on growth across time, experience, and level. In other words, our competency framework contains progression-based rubrics, which we call “continua,” that have student-facing indicators to describe how a skill increases in sophistication across six performance levels. These continua are built to be used by any student and teacher, K-12. And they are directly sourced from nationally validated standard sets. To learn more, check out our 3-part webinar series:

Activity #3 – Calibrating and Creating Common Understandings

Our final activity again places participants in the position of a teacher who must rate a student presentation using the NGE.2 Presentation continuum. For this activity, we engage in a student-work calibration protocol, which has three stages:

- Watch the presentation and rate three of the six skills individually. Submit to an online form.

- In groups of 4-5, share your ratings and work to build consensus.

- Finally, as a whole group, debrief the process and share “anchor scores” created by the designers of the continua.

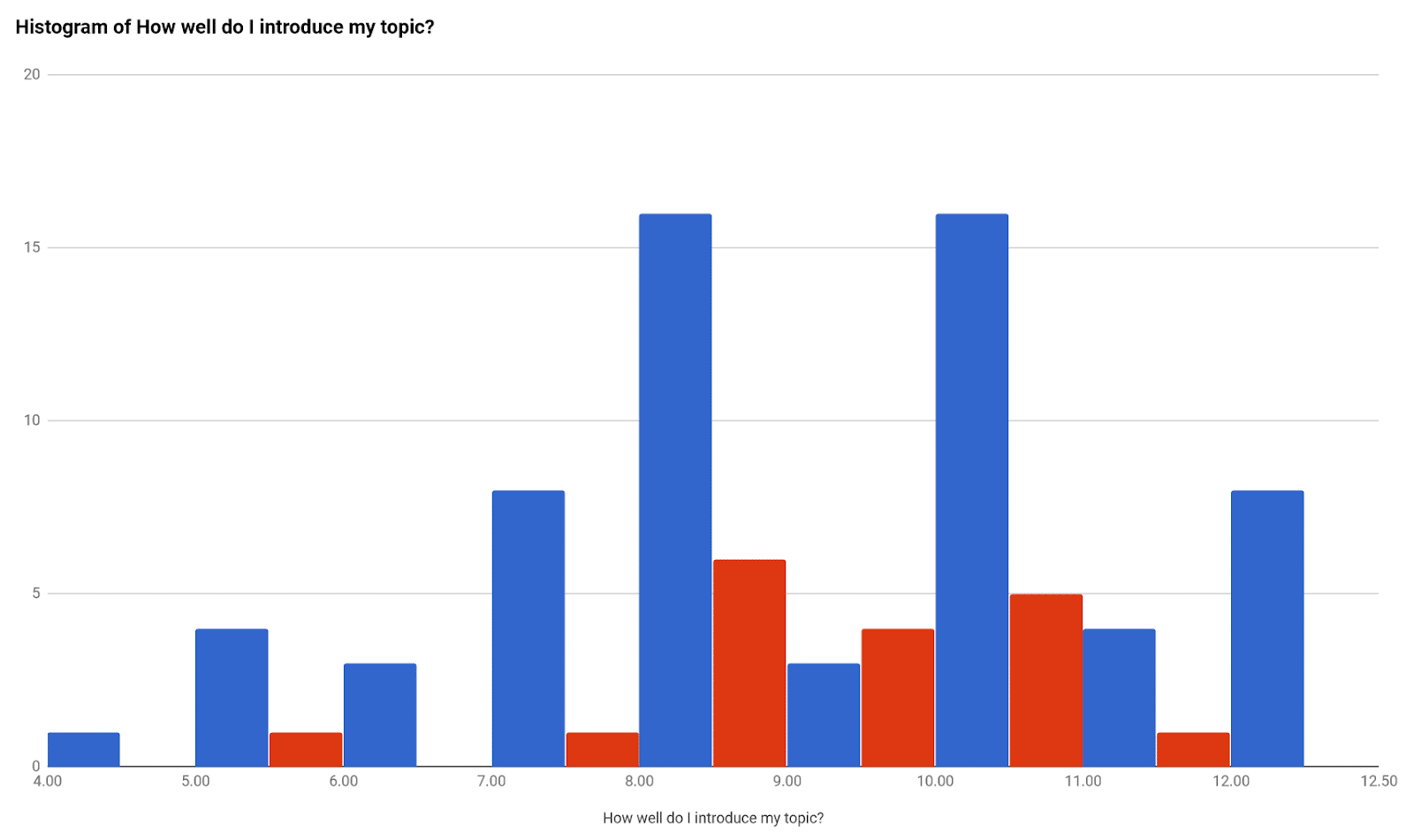

After each step, we take a look at the results. The following graphic is a histogram showing where the ratings fall across the group for the skill, entitled “NGE.2.1 standard ‘How well do I introduce my topic?’” Each blue bar represents an individual participant’s rating for this skill. Notice how the blue bars vary, spanning from 4 to 12, with most ratings between 7 and 12. The red bars represent the group consensus ratings. The goal is for the red bars to show less variability. In this example, most group ratings fall between 8 and 10.

We emphasize that this activity is not meant to create perfect harmony among raters—that’s impossible. Rather, we find there are three main benefits:

- Create a common understanding for how the tool should be used

- Limit, to a practical degree, the variability in ratings across teachers

- Help all teachers rate competencies that typically exist outside their subject areas

Creating common understanding is the most important benefit of this activity. We advise participants, when they come to an impasse within the group, pause and ask each person to share what feedback they would give to the student to get them to the next level on the continua. The lively debate about what rating to give or what it means to have a “compelling hook,” while important, must transition back to a focus on the student. Yes, the continuum is a tool to rate student work, and teachers might not always agree on those ratings. But equally important is the feedback given to the student to improve their work.

More Building 21 Activities and Resources

Participants ALWAYS ask how ratings from the continua are tracked in a gradebook. They also pose a series of questions:

- What is the relationship between ratings of skills and grades of traditional courses?

- How do students earn credit?

- What do report cards look like?

- What are the implications for the transcript?

These are all really important considerations!

The short answer is that our model was created to replace these traditional structures. In fact, we created our own information system to replace traditional courses, credits, and report cards, because we couldn’t find anything to track student progress the way we want. The problem is that there are not many public districts or schools that can take such radical measures to replace all time-based, age-based, course-based, and grade-based structures.

In a 3-hour version of this workshop we spend time discussing these questions (Activities #4, #5, #6). We also cover many of these questions in the third session of our webinar series. For schools in the Building 21 network, we create guidelines, conversions, and clever-work-arounds to help our school leaders and teachers transition to a competency-based model. This is the most complex part of the work because traditional factory-model structures, in many ways, inhibit personalization.

Trying to do all of this adequately in a single workshop is incredibly difficult; we hope to at least make a dent and get the conversation started.

Learn More

- Breaking out of the Boxes at Building 21

- Building 21’s Competency Dashboard

- Building 21: Designing a Network for Competency-Based Education

- The Competency Train Pulls Into Kankakee: Common Start-up Challenges and Strategies

Thomas Gaffey joined Building 21 after seven years as a 9th grade math teacher at Philadelphia’s School of the Future (SOF) where he utilized problem-based and technology-driven learning approaches to support students in tackling real-world problems. Thomas was also the Director of Educational Technology at SOF, managing their one-to-one laptop program. As a Microsoft Innovative Educator master trainer and founder of What If Partners, LLC., Thomas has led professional development for teachers and school districts nationally. As the Chief Instructional Technologist at Building 21, Thomas co-created the Learning What Matters (LWM) Competency Framework and the Building 21 instructional model, developed a Google Apps-based prototyping system for data dashboards, and designed a competency-based LMS within the open source platform, Slate. He is now leading an expansion effort to help districts across the country use the Learning What Matters (LWM) competency framework to personalize education for students.

Thomas Gaffey joined Building 21 after seven years as a 9th grade math teacher at Philadelphia’s School of the Future (SOF) where he utilized problem-based and technology-driven learning approaches to support students in tackling real-world problems. Thomas was also the Director of Educational Technology at SOF, managing their one-to-one laptop program. As a Microsoft Innovative Educator master trainer and founder of What If Partners, LLC., Thomas has led professional development for teachers and school districts nationally. As the Chief Instructional Technologist at Building 21, Thomas co-created the Learning What Matters (LWM) Competency Framework and the Building 21 instructional model, developed a Google Apps-based prototyping system for data dashboards, and designed a competency-based LMS within the open source platform, Slate. He is now leading an expansion effort to help districts across the country use the Learning What Matters (LWM) competency framework to personalize education for students.