How Standards-Based Grading Led Us to Empower, Part 2: The Power of Evidence

CompetencyWorks Blog

Increased interest in student-centered learning management systems that support equitable assessment and student self-direction as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic further amplify the value of this excellent two-part series that was originally posted on the Edtech Elixirs blog. Adam Watson is Digital Learning Coordinator for Shelby County in Kentucky, a district that’s deeply devoted to competency-based education.

When our district began a move to standards-based grading (SBG), we realized that we needed a different digital tool. In the previous blog entry, I discussed how the limitations of a traditional grading system led us to SBG, and ultimately, Empower Learning. In this entry, I give an overview on the grading features of Empower and how it integrates with our standards-based learning philosophy.

While Empower is a fully functioning learning management system, its core capability of capturing student evidence and calculating this for overall standard scores is really the “crown jewel” of the tool.

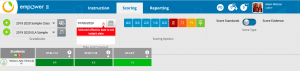

But first, what do you see when you log into Empower? There are three main interface tabs. The Instruction Tab is where you can see classes (either fed from your student information system or custom-created groups), as well as create and assign instructional materials like Activities and Quizzes. The Reporting Tab is where you can output progress reports and export other data. The Scoring Tab is where “gradebooks” are located, and the place where evidence and standards are scored. (Remember, as is necessary in SBG, these scores are based on established Mastery Scales—for Shelby, these range in whole numbers from 0 to 4.)

Empower has two types of gradebooks. The first is a class’s default gradebook (also called the “master course playlist” by Empower), designed and managed at the district level, that designates the prioritized standards for the course. This master gradebook determines many important reporting and analytical aspects of Empower, such as progress reporting and the final course-grade calculation. (In a knowing nod to a traditional system needing a final “number” grade at the end of the year for secondary classes, Empower can take the end-of-year scores of all the prioritized standards and average them together.) The second type are gradebooks custom created by the user, in order to help teachers focus on a smaller lens of standards (perhaps just a few standards addressed in your Unit One) or to make cross-content project assessment much easier (think of project-based learning possibilities!).

Under the Scoring Tab, you can toggle between “Score Standards” and “Score Evidences,” which show the interrelationship between the two—they are truly two sides of the same coin. Under “Score Evidences,” you can see tasks that have been targeted to various standards and score these individual evidences accordingly. These may have been created in the Instructional area, such as Activities and Quizzes, but one of my favorite Empower features is the ability to make “Quick Evidence”—within a button push and a few clicks, you can quickly create and score evidence. (Many learning management systems only allow grading of digital activities created inside its system, but Empower allows you to score and assess virtually anything in seconds—analog activities, observation of classroom discussions, and so on.)

Under “Score Standards,” a teacher can score an overall standard if they wish. However, one of Empower’s most powerful tools is the Marzano True Score Estimator (MTSE), which is accessible within a gradebook’s “Standards” toggle side. You can use it to look behind a particular standard, and not only examine the body of evidence each student has demonstrated, but see how Empower calculates and projects an overall standard score based on the evidence score numbers and when the evidence occurred. To do this, Empower actually runs the evidence scores through three different formulas—average, Linear, and Power Law—then recommends one or more as the most reliable for the given set. This creates a completely different nuance to grading (which constantly updates as new evidence is entered), and a very necessary one when deciding and defending a student’s mastery of a standard.

Let’s briefly walk through these formulas. We are very used to averaging, but I will highlight here that it is the only one of the three formulas that is indifferent to when the evidence scores happened—in other words, whether the scores were from two years ago, last September, or yesterday. Linear is looking for a trend line; if we graphed these scores, are we trending upwards or downwards? Therefore, more recent evidence is important when determining the direction of the trend. Lastly, Power Law is based on an intuitively typical human learner. When most of us encounter a new concept, we struggle to understand it, and if we were “scored” on our skill or knowledge, would likely score low with 1’s and 2’s. As time and experience went on, we would get better, likely scoring 2’s and 3’s, and in time would achieve mastery with 4’s. Power Law takes that progression into account by mathematically counting earliest scores with considerable less weight, and mathematically counting most recent scores with considerably more weight. In short: for Power Law, how you just performed is much more important than your potential low scores in the early part of your learning.

Take a moment to compare these multiple, nuanced levels of assessing learning to the story of Timmy (from Part One of this blog series) and his traditional grading conundrum. Like many students, he struggled with such a low test score early in a unit that it didn’t matter that he aced the final test. In a traditional system of averages and percentages, only a student who is freakishly perfect from the start would maintain a high grade, and a student who starts off poorly cannot avoid the demotivating academic hole they can’t statistically crawl out of.

Empower changes the entire approach to looking at what grading is communicating, and, at least as importantly, gives students specific guidance on how to improve their learning. They know not only their overall strengths and challenges on a given standard, but also how their evidence behind a standard has an accumulating history. They know that the importance of today’s performance is actually calculated as more important than whatever struggles the student may have had earlier. (There is an additional positive side effect of this as well: students that perform exceptionally well at the beginning of an academic year cannot rest on their good laurels and coast into a passing grade when “spring senioritis” sets in and their present performance significantly drops.)

I admit that when I first began learning and teaching others about how Empower calculates scores, I struggled to understand and explain this well to others. As the school year began, I created a Scoring Calculations Doc to help explain how this worked to our district staff. For the sake of this blog entry, I’m only bringing the Doc up to point out one common concern that parents, students and even some teachers have: in a system of mastery scales and standards-based grading, will final course grades, GPA’s, etc. go down for most students?

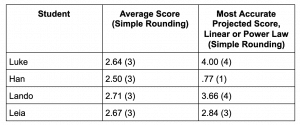

In the Doc, I attack this head on by using a fictional set of four students and examining their evidence scores under a single hypothetical standard. Luke is the Marzano ideal student of human learning, who starts with scores of 1’s, then 2’s and 3’s, and finally 4’s. Han is the opposite: he started at all 4’s and wound down to 1’s in several recent scores. Lando is all over the place scorewise for a while, but settles out and eventually scores consistent 4’s by the end of his scoring timeline. Lastly, Leia has mid-level scores fairly consistently, although she tends to score 3’s (including recently).

When comparing the simple average of the scores versus their Linear/Power Law projected calculations, the above table shows how the idea of averaging conflates the academic “stories” of these four students as equal, when we can see this is limiting at best and strongly inaccurate at worst. Interestingly, in a mastery SBG system that goes beyond merely averaging, three of these students do as good or better than they would in a traditional grading system. With SBG, there is not only more of a chance for a student to score a higher GPA, but such a GPA may actually reflect a true accomplishment of (mastery) learning instead of just an accumulation of points. Out of our four fictional friends, the only student that does worse in SBG—Han—is the one student we can clearly see is “bottoming out” or having a bad case of the senioritis we mentioned earlier, but instead of facing an academic penalty for this in traditional grading, Han would unfairly coast into the same grade as his peers.

Empower is an example of a powerful digital tool that is a potential game changer for assessing student learning. Of course, a learning management system is merely a holder of digital data entered by humans—it cannot replace a teacher’s professional judgment and relationship building necessary for student learning and growth to occur. Empower can calculate scores quantitatively, but has no ability to determine the qualitative nature of the assessments themselves; this is where “the art of teaching” and a teacher’s discernment come into play. (This is one reason why Empower always allows a teacher to determine an overall standard score, even if that means overriding what Empower suggests based on evidence scores.) Empower does not magically make teachers effective in standards-based grading practices or make their assessments automatically any deeper, more rigorous, or more authentic.

Excellence in SBG requires dedication, professional learning, and time. Empower does not short cut this or offer a silver edtech bullet. However, I do have to say that in the six years I have been a part of education technology in Shelby County, there have been few if any digital tools that have pushed and challenged our teachers to teach transformatively as much as Empower. It is impossible to use it fully and faithfully and still maintain a traditional grading mindset. In that same vein, as we continue to support and fulfill our current Strategic Leadership Plan, tools like Empower are a valuable asset in order to move forward in our goal to enrich and enlarge our capacity to personalize our students’ learning with a “mastery of standards” philosophy, and leave behind the idea of school as a game of compliance and points.

Learn More

- How Standards-Based Grading Led Us to Empower, Part 1: The Tyranny of 82%

- Student-Designed Performance Assessments for Personalized Learning and Student Agency

- Summative vs. Formative Assessment: From Binary Choice to Continuum

Adam Watson has been an educator in Kentucky since 2005. He began as a high school English teacher, eventually becoming Teacher of the Year at South Oldham High School in 2009 and getting Nationally Board Certified in 2013. Adam was hired in 2014 by the Shelby County Public Schools to help lead their 1:1 initiative, and is currently their Digital Learning Coordinator. He is a frequent professional development presenter and session leader at conferences and institutions in Kentucky and beyond. In 2019, Adam was awarded KySTE Outstanding Leader of the Year.

Adam Watson has been an educator in Kentucky since 2005. He began as a high school English teacher, eventually becoming Teacher of the Year at South Oldham High School in 2009 and getting Nationally Board Certified in 2013. Adam was hired in 2014 by the Shelby County Public Schools to help lead their 1:1 initiative, and is currently their Digital Learning Coordinator. He is a frequent professional development presenter and session leader at conferences and institutions in Kentucky and beyond. In 2019, Adam was awarded KySTE Outstanding Leader of the Year.