Personalized, Competency-Based Learning Can and Should Replace Tracking – Here’s Why

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post originally appeared at KnowledgeWorks on November 16, 2021.

The only way to undo racism is to consistently identify it and describe it – and then dismantle it.

-Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019)

There’s an essential truth we want more folks in education to recognize: tracking—the widespread practice of labeling, ranking, sorting and separating students, our children, by perceived academic ability and behavioral compliance—is bad, really bad. Its origins are racist and its current renditions in our schools perpetuate oppression and produce harm. The impact of tracking is particularly bad for students already facing multiple forms of injustice in and outside our schools. The data proving this fact are everywhere. That’s why we argued that when it comes to tracking, it’s inaccurate to say inequity is a symptom; it’s not really even an outcome. With tracking, inequity is a principle of design. The system is working as intended. That’s why we need to dismantle it.

Once folks begin to face this fact, they inevitably confront the difficult realization that if we’re to dismantle all the systems, policies, procedures, and practices that compose tracking’s infrastructure, we’ll need to replace it with something else. That something needs to be a learning infrastructure ready to scale, ready to re-shape instruction and assessment, ready to shift mindsets, ready to inspire educators and students and parents and communities to rebuild learning environments so they prioritize belonging, growth, agency, self-efficacy, autonomy, and cultural responsiveness.

Fortunately, that replacement infrastructure already exists.

Personalized, competency-based learning replaces tracking

Those who lead and work within our schools often find it daunting to extricate themselves from traditional ways of “doing school” in part because many directly benefitted from those designs and because compelling alternatives to those approaches have yet to be presented. Many educators, leaders and parents cannot conceive of a school design that departs from separate and accelerated opportunities for “gifted” students, and isolated and remediated instruction for “struggling” learners. Needing to see it to believe it, some folks are reticent to abandon their cultural and professional training until they can be shown an alternative that offers more gain than loss. Even the most well-intentioned folks can be leery of accepting new ways of operating if they get stuck in old assumptions and problematic practices. We get that. Systemic change is hard. And changing beliefs can be even harder. But once we honestly and critically face what tracking is and what it does, we can’t ignore that we must do things differently and push through the reticence toward brighter horizons.

Here’s the good news: Those who have deeply investigated and implemented personalized, competency-based learning typically recognize that the rationale for tracking—and the practices and policies on which it depends—is soon stripped of its legitimacy. Once folks see how to keep students together socially and individualize instructional activities to build on the unique needs, assets, and contributions each student possesses, tracking just doesn’t make sense anymore. It’s really this simple: schools don’t need to track once the logics and systemic practices of personalized, competency-based learning are established.

Want evidence for this? Twenty years ago, Oakes (1992) named three core challenges faced by those who sought to de-track schools:

- Normative challenges, based on long-standing beliefs that young persons differ by ability and that schools should be structured to address those differences

- Political challenges, reflecting the difficulty of overcoming vested interests in tracking, such as those held by parents who are ambitious for their high-achieving children and by teachers who enjoy teaching honors classes

- Technical challenges, reflecting the difficulty of instructing students of widely varying levels of performance, a task for which few school systems are prepared

Building on Oakes’ observation, Gamoran notes that most of the emphasis in de-tracking scholarship and strategies has been “on the normative and political challenges, reasoning that if these challenges could be surmounted, the technical difficulties could be easily overcome.” He notes, however, that evidence to the contrary has accumulated.

[F]ailure to solve the technical problems of mixed-ability teaching is a major impediment to addressing the normative and political challenges. While the technical challenges have defied easy solution, recent work has identified conditions under which effective teaching in mixed-ability contexts may be more successful than in the past.

We believe personalized, competency-based learning supplies necessary technical solutions to allow reformers to tackle both normative and political challenges. We also believe that if we do so we will be establishing the conditions for the achievement of equity.

For this reason and a bunch more, personalized, competency-based learning is ideally suited to become tracking’s replacement infrastructure and thereby function as an equity catalyst. And because tracking is inherently racist, this personalized, competency-based learning replacement, particularly when applied with a racial equity lens, can function also as an anti-racist strategy.

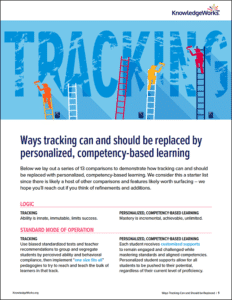

Ways tracking can and should be replaced by personalized, competency-based learning

Below we lay out a series of 13 comparisons to demonstrate how tracking can and should be replaced with personalized, competency-based learning. We consider this a starter list since there is likely a host of other comparisons and features likely worth surfacing—we hope you’ll reach out if you think of refinements and additions.

Below we lay out a series of 13 comparisons to demonstrate how tracking can and should be replaced with personalized, competency-based learning. We consider this a starter list since there is likely a host of other comparisons and features likely worth surfacing—we hope you’ll reach out if you think of refinements and additions.

Download a printer-friendly PDF of the information below and share it with an educator, administrator, parent/guardian, community leader, student, district official, and/or policymaker.

Tracking |

Personalized, Competency-Based Learning |

|

| LOGIC

|

Ability is innate, immutable, limits success.

|

Mastery is incremental, achievable, unlimited.

|

| STANDARD MODE OF OPERATION | Use biased standardized tests and teacher recommendations to group and segregate students by perceived ability and behavioral compliance, then implement “one size fits all” pedagogies to try to reach and teach the bulk of learners in that track.

|

Each student receives customized supports to remain engaged and challenged while mastering standards and aligned competencies. Personalized student supports allow for all students to be pushed to their potential, regardless of their current level of proficiency.

|

| RESEARCH BASIS | Eugenics, The Bell Curve, racism, classism, fixed notions of “intelligence,” segregation, apartheid, White supremacy. | Agency, motivation, engagement, belonging, growth mindsets, self-determination theory, self-efficacy, expectancy-value theory, self-regulation, culturally-sustaining pedagogy, anti-oppressive pedagogy, border pedagogy, critical race theory, LatCrit, DisCrit, subtractive schooling, deeper learning, zone of proximal development, social learning theory.

|

| MINDSET | Fixed. Struggle is bad. It is evidence of insufficient ability, intelligence, commitment, or preparedness for success. Struggle demonstrates what a student cannot do. If students struggle in an activity or content area, they may not be cut out for success in that domain. If students need to slow down or re-learn something, that demonstrates they are incapable of learning the material at the pace others may be learning it. Such students will be unlikely to catch up so they should be separated.

|

Growth. Struggle is good. Struggle is evidence of the edge of the learner’s current competency. Struggle is encouraged not pathologized, and failure is understood to be part of the learning process. Improvement is assured with effort, help, resources, access, and time. If a student needs to slow down or re-learn something, that’s normal and expected; it only demonstrates a need to differentiate the learning activity or temporarily change the pace. Students can catch up and take multiple paths toward mastery.

|

| INTENTION | Secure unearned advantage for over-resourced students and families. Rank and sort children and youth to provide justification for arbitrary and discriminatory social hierarchies. Provide ample supply of cheap unskilled labor and thereby maximize profits for the elite. Convince individuals that their socioeconomic position is an inevitable and natural consequence of their biology. Present schools as meritocracies. | Establish meaningful and equitable opportunities to excel so all students are prepared to flourish in post-secondary college and career. Inspire mastery of content, commitment to lifelong learning, knowledge of how to learn, and proficiency in 21st century skills. Democratize access to opportunity to stabilize schools, communities, the economy and our nation, and reduce status differences that drive social discord. Give all kids a chance at a bright future.

|

| PURPOSE OF ASSESSMENT | Assessment is for ranking and sorting. To prove which students merit “advanced” or “gifted” labels and which will be given an assortment of low-expectancy classifications (“low,” “struggling,” “college prep,” “honors,” etc.).

|

Assessment is for learning. To capture what students can do now, and plan for what they will do next to keep growing in their competencies. |

| PATHWAYS | Ruts to constrained, if not pre-determined and foreclosed, post-secondary college and career options. | Personalized and open opportunities to explore interests, demonstrate growth, and achieve forms of measurable mastery that are valued in post-secondary college and career settings.

|

| PACING | Keep up with the teacher’s or school’s arbitrary milestones or fall behind and either receive lowered grades, lose course credit, or get diverted to lower tracks. | Learners advance within the learning continua after demonstrating competency in ways that are meaningful, relevant, and purposeful to each learner (examples of learning continua here and here). When utilizing learning continua, learning is the constant and time becomes the variable.

|

| ENRICHMENT OPPORTUNITIES

|

Only allocated for “gifted” learners.

|

For all students, whenever they need them.

|

| ACCELERATION OPPORTUNITIES

|

Acceleration and enrichment for the ‘gifted’ few. Remediation and isolation for the rest.

|

Acceleration and enrichment for all. Extra scaffolds, resources, and instruction whenever needed.

|

| WHAT GRADES SHOW

|

Grades are threats. They are designed to scare students into completing work. They mostly measure student behaviors, students’ socioeconomic circumstances, or their position within racial / gender / (dis)abled / linguistic hierarchies.

|

Grades may be nonexistent, but if present reflect the level of mastery a student has achieved in a given domain of inquiry.

|

| ETHIC | You either have it or you don’t. Sink or swim. Compete against others to be “the best.” | Everyone challenged, everyone supported, every day. Everyone working at the edges of their current and always expanding abilities. We lift as we rise. We collaborate with others to do our best and help others to do the same.

|

| MEASURES | Wide variability and bias in standardized assessments used to determine “ability,” plus ample evidence of racial / gender / class / linguistic / cultural bias in teacher recommendations used to determine placement. Parents with abundant social and cultural capital are more able to “game the system” to secure their child’s advantage, which perpetuates the “rich get richer” outcomes intrinsic to tracking regimes. Little to no agreement of what constitutes an ‘A’ or a ‘B’ or a ‘C’ or ‘failing’ even among teachers who work in the same grade or department.

|

Transparent and often teacher/student/family co-produced assessments of mastery aligned with curriculum standards set by the state, some of which have established levels of validity and reliability that permit scaling. |

We believe that each learner must have access to the tools, supports, and experiences needed to graduate ready for what’s next. Tracking is anathema to this goal. Personalized, competency-based learning, however, establishes engaging educational experiences that are customized to each learner’s strengths, needs, interests, and funds of knowledge. In a personalized, competency-based learning environment, students have voice in and ownership over how, what, when, and where they learn and connections to community and real-world experiences are a priority.

In a personalized, competency-based learning environment, students learn actively using different pathways and varied pacing that does not result in tracking or other forms of ability grouping. Each of these core elements of personalized, competency-based education—engaging experiences, a focus on the learner’s individual needs and assets, student agency and autonomy, connections to real-world experiences and preparation, and de-tracking—have a substantial body of research and evidence supporting their efficacy in closing opportunity gaps and producing more equitable outcomes. And because personalized, competency-based learning can be used to dismantle and replace the racist origins of and current harms produced by tracking, it functions as a scalable, student-centered, anti-racist remedy. Let’s do this!

So what’s next?

- Download the table and share it with an educator, administrator, parent/guardian, community leader, student, district official, and/or policymaker and ask to discuss its implications with them.

- What do members of your community say when they explain that de-tracking can’t be done in your neck of the woods? What reasons do they offer for why “it can’t be done here”? Which items in the table above might help them to see a way forward, to commit to de-tracking?

Learn More

- Teachers Making the Shift to Equitable, Learner-Centered Education

- Dangerous Conversations: The Importance of Empathy, Grace, and Skill

- Designing for Equity: Leveraging Competency-Based Education to Ensure All Students Succeed

Eric Toshalis, EdD, has served public education for more than two decades—as a middle and high school teacher, coach, mentor teacher, teacher educator, teachers’ union president, community activist, curriculum writer, researcher, author, professor, and consultant. Dr. Toshalis is the author of the award-winning book, Make Me! Understanding and Engaging Student Resistance in School (2015), and is co-author of the widely-used text, Understanding Youth: Adolescent Development for Educators (2006), both by Harvard Education Press. As the senior director of strategic initiatives, he helps shape KnowledgeWorks’ impact in the field with a particular focus on and for historically marginalized youth. Prior to joining KnowledgeWorks, Eric was senior research director at Jobs for the Future (JFF), where he used research and cross-disciplinary partnerships to build the evidence base for student-centered learning. Eric also serves as a member of the CompetencyWorks Advisory Board.

Eric Toshalis, EdD, has served public education for more than two decades—as a middle and high school teacher, coach, mentor teacher, teacher educator, teachers’ union president, community activist, curriculum writer, researcher, author, professor, and consultant. Dr. Toshalis is the author of the award-winning book, Make Me! Understanding and Engaging Student Resistance in School (2015), and is co-author of the widely-used text, Understanding Youth: Adolescent Development for Educators (2006), both by Harvard Education Press. As the senior director of strategic initiatives, he helps shape KnowledgeWorks’ impact in the field with a particular focus on and for historically marginalized youth. Prior to joining KnowledgeWorks, Eric was senior research director at Jobs for the Future (JFF), where he used research and cross-disciplinary partnerships to build the evidence base for student-centered learning. Eric also serves as a member of the CompetencyWorks Advisory Board.

Virgel Hammonds is the Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks. In his role, Virgel partners with national policymakers and local learning communities throughout the country to redesign learning structures to become more learner-centered and based on proficiency, rather than seat time, and which promote both teacher and learner agency. He also works with KnowledgeWorks staff to build out competency education tools and services to help districts implement personalized learning. Virgel previously served as the superintendent of RSU 2 School district in Maine and as a high school principal at Lindsay Unified School District in California. In Lindsay, he helped implement a personalized learning model where “learners” didn’t earn letter grades, but rather are awarded mastery for subjects in which they’ve proven to be proficient. Virgel also serves as a member of both Aurora Institute Board and CompetencyWorks Advisory Board.

Virgel Hammonds is the Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks. In his role, Virgel partners with national policymakers and local learning communities throughout the country to redesign learning structures to become more learner-centered and based on proficiency, rather than seat time, and which promote both teacher and learner agency. He also works with KnowledgeWorks staff to build out competency education tools and services to help districts implement personalized learning. Virgel previously served as the superintendent of RSU 2 School district in Maine and as a high school principal at Lindsay Unified School District in California. In Lindsay, he helped implement a personalized learning model where “learners” didn’t earn letter grades, but rather are awarded mastery for subjects in which they’ve proven to be proficient. Virgel also serves as a member of both Aurora Institute Board and CompetencyWorks Advisory Board.