Replacing the Grammar of Schooling with Competency-Based Innovations

CompetencyWorks Blog

Links to other posts in this series by Sandra Moumoutjis are at the end of this article.

As we begin rethinking the traditional structures of school, we should keep in mind the lessons we learned during the pandemic, specifically related to equity and access. First and foremost, there is a need for schools or places where children can physically attend. The in-person learning communities that schools offer cannot be fully replicated virtually for many students. We also need the supports and services schools provide to their students and families. And we need predictable days and times during the year that children are in school, hopefully safe and being cared for. But how we organize teaching and learning inside that predictable school day is what we need to challenge ourselves to reimagine.

If you have been following my blog series, you probably know that I am going to start by asking one very important question: “Why?” Why are we still bound by outdated age-based, grade-based, time-based, course-based, and content-driven structures created over a century ago in the factory school model design? Why do we insist on failing students? Why is learning bound by time? Why does a student need to take eight different subjects for 45 minutes every day? With all the changes that have occurred in the last one hundred years, why are we unable or unwilling to break free of the constraints of these traditional structures?

The question we must really ask ourselves is, what do we believe the true purpose of school is? The traditional structures of school are built for adults to sort, rank, and control students. Many people will argue that we cannot change these structures because our states require course, credit, and grade reports or that colleges expect a transcript with courses, credits, grades, and a GPA, so we must deliver that. No doubt, there is work to be done with state education departments to create the enabling conditions for competency-based education to thrive and to create alternate competency-based pathways to graduation. There is also work to be done with post-secondary institutions to change their thinking and requirements for sorting and ranking students in the acceptance process. But let’s leave that aside for now, holding the belief that these are problems we can and will solve.

It is not just the external pressures that keep these structures in place; it is often the resistance of the adults to let go of these comfortable and familiar structures that prevents change from occurring. Adults often say things like, “School isn’t supposed to be fun. I hated school. It’s just how it is.” There is also a belief that it is not worth the time or effort to change these traditional structures, so we should stop trying to change them and just innovate within them. I strongly believe that the only way we can truly innovate is by rethinking and replacing these traditional structures to transform schools into student-centered learning communities that value the growth and progress of every learner.

Speaking at a forum on education reform in 2012, Richard Elmore, who was one of the nation’s most prominent educational thinkers, declared: “I do not believe in the institutional structure of public schooling anymore.” He then acknowledged that his work helping teachers and leaders improve their practice is “palliative care for a dying institution.” Elmore believed it was these traditional structures that were preventing real learning from happening in our schools, especially in high school, which he called, “the second- or third-most dysfunctional institution in American society.”

In fact, Richard Elmore’s challenge to the field—specifically, “How can we reimagine the grammar of schooling [e.g., age-based, time-based, course-based structures] to support the learning and growth of young people and adults in schools?”—was the catalyst behind Building 21’s founding. For it was in one of Dr. Elmore’s classes at Harvard, in response to this prompt, that our founders Chip and Laura sketched out the initial blueprint for what became Building 21. Richard Elmore challenged every assumption by pushing his students to ask, “How do we decouple this thing called learning from this place called school?” and “What is worth learning, and how do we know it is being learned?” Good questions, indeed, and ones that we are still grappling with today across the field.

So my challenge to you today is to forget everything you know about what school is and reimagine what learning could be in this place called school.

How do we restructure our schools to become student-centered learning communities that value student growth and progress and are focused on relevant, meaningful, and rigorous learning experiences that challenge students to be curious, ask questions, and investigate and solve problems?

In order to rethink traditional structures, you have to replace them with something. Rethinking traditional structures does not equate to having no structures at all. This is a common misconception about competency-based education. In fact, a competency-based framework provides the necessary structure to replace age-based, grade-based, time-based, course-based, and content-driven structures in a way that truy places the learner at the center. No longer is the focus on seat-time; it is now on learner progress and growth on the competencies over time. In CBE schools, learning is the constant, time is the variable. No longer is the focus on content memorization but content becomes the context through which students apply and demonstrate their progress and growth on the competencies. No longer is the gradebook owned by the teacher but it is now owned by the student and demonstrations of learning can happen anytime, anywhere, all contributing to a student’s competency portfolio.

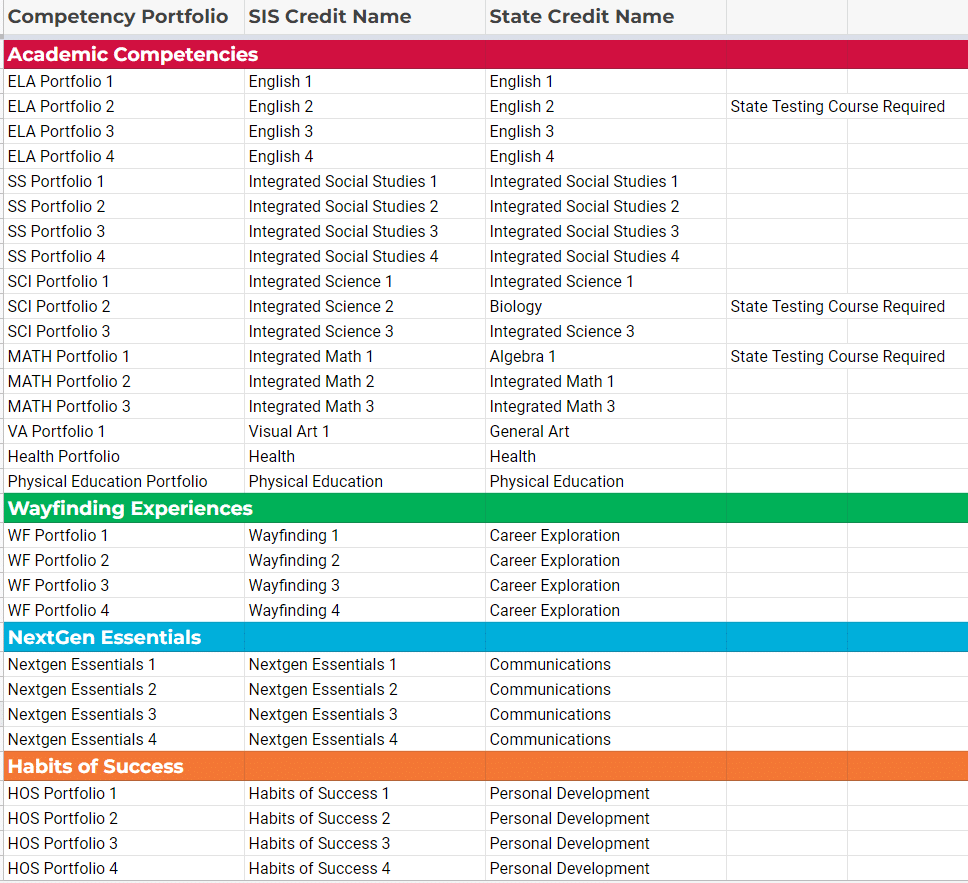

As we work mostly in public school districts, we have had to do some back-end work to map our Competency Framework to traditional courses and credits. (As I mentioned before, it is our hope to work with state education departments to rethink some of the reporting and graduation requirements.) At our Building 21 Allentown high school, we worked with the Allentown School District to change our graduation requirements. We created a set of unique competency portfolio credits aligned to our competency framework. We then mapped these credits to the required state courses and rostered students to these courses in the student information system, as shown below.

Although these credits appear to be traditional Carnegie units, they are not based on seat time. For example, students do not sit in a course called NextGen Essentials for a semester or a year. Instead, they receive ratings for the NextGen Essentials competencies—Project Quality, Presentation, Collaboration, and Written Communication in the Workplace—from a variety of teachers and learning experiences. When they have enough evidence to complete their portfolio, they receive a credit in the student information system (SIS).

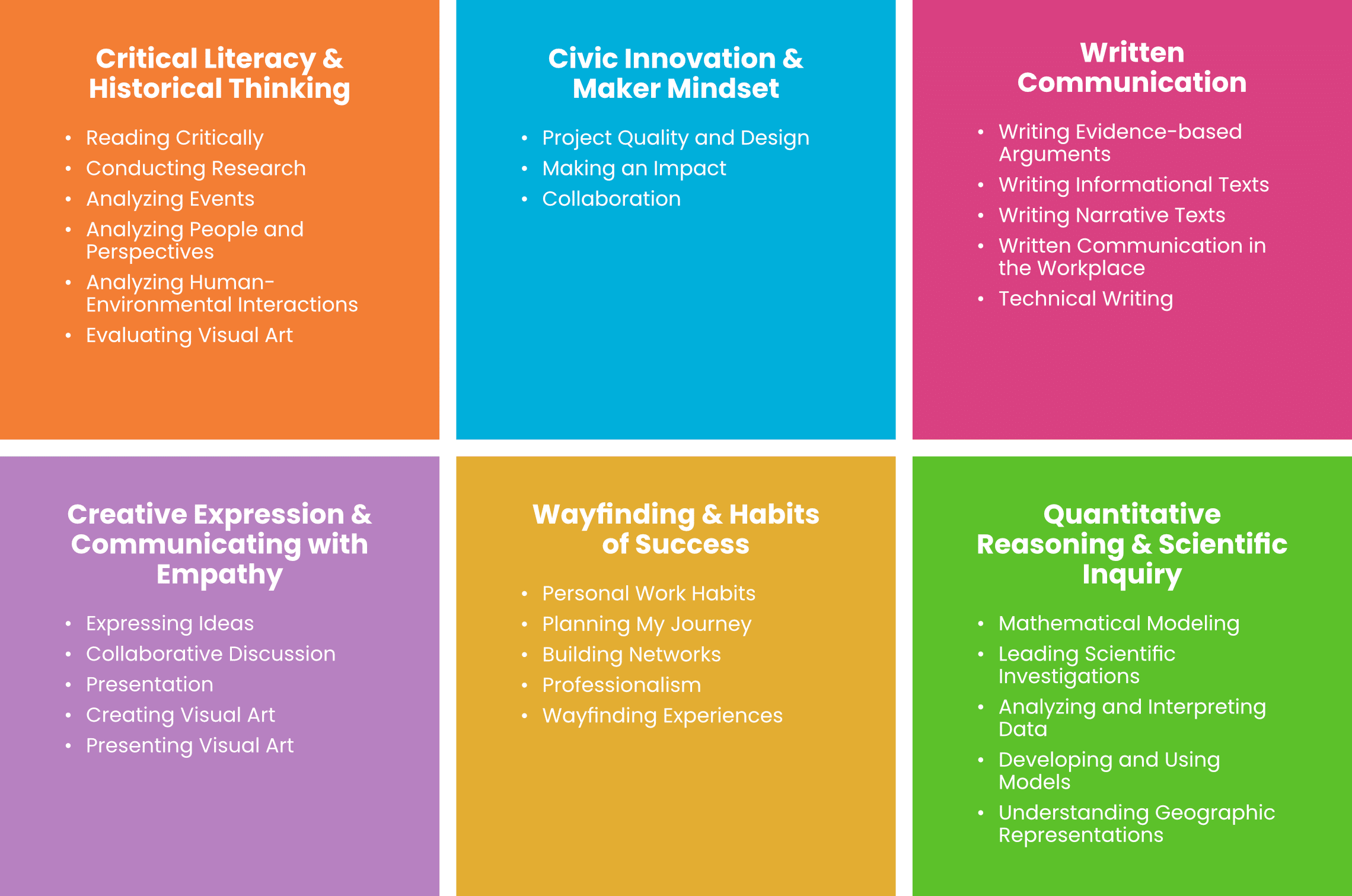

We have also been working with the Mastery Transcript Consortium (MTC) to create a truly competency-based transcript. Our goal is a transcript that transparently communicates what students know and can do, as opposed to how they spent their time in school. We reorganized our competency credit areas, as shown below, and created criteria for foundational and advanced competency credit.

In both crediting options, students have the opportunity to earn advanced credit by meeting higher performance levels on our continua, instead of adults deciding who should and shouldn’t be in honors classes.

As we try to reimagine school without the traditional structures, we have to acknowledge that there are barriers to overcome. My next blog will focus on rethinking time in CBE schools and how we can use the master schedule to reorganize teaching and learning to break down traditional structures. I will then explore the barriers that traditional time-based, course-based, and teacher-facing systems present to tracking and communicating competency growth and progress over time and share the systems and dashboards we have used and created to eliminate those barriers. Until then, let your imagination wander as you explore the possibilities for what learning could look like in this place called school.

Learn More (other posts in this series)

- Why Should Schools Transition to Competency-Based Education?

- Preparing for Your Competency-Based Education Journey: A Process for Success

- Building 21’s Teacher Competencies to Facilitate Competency-Based Learning

- Building 21’s Leadership Competencies to Facilitate Competency-Based Learning

- Building 21’s Studio Model: Designing Learning Experiences for Engagement and Impact

Sandra Moumoutjis is the Executive Director of Building 21’s Learning Innovation Network which is designed to grow and support a community of schools and districts as they transition to competency-based education. Through professional development and coaching, Sandra supports schools and districts in all aspects of the change management process. Sandra is the co-designer of Building 21’s Competency Framework and instructional model. Prior to working for Building 21, Sandra was a teacher, K-12 reading specialist, literacy coach, and educational consultant in districts across the country.

Sandra Moumoutjis is the Executive Director of Building 21’s Learning Innovation Network which is designed to grow and support a community of schools and districts as they transition to competency-based education. Through professional development and coaching, Sandra supports schools and districts in all aspects of the change management process. Sandra is the co-designer of Building 21’s Competency Framework and instructional model. Prior to working for Building 21, Sandra was a teacher, K-12 reading specialist, literacy coach, and educational consultant in districts across the country.