Supporting Teachers with Making Sense of Proficiency-Based Learning

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second in a three-part series from Andrew Jones, director of curriculum at Mill River Unified Union School District in Vermont.

For many teachers, proficiency-based learning (PBL) is a significant shift from past practice. Though certain aspects of PBL are familiar to some teachers, putting proficiency into consistent practice can be a heavy lift. This shift requires new knowledge and skills, while simultaneously jettisoning numerous past practices. Building teacher capacity is a central requirement for ensuring the successful implementation of PBL. Without time to make sense of the shift and opportunities for new learning, teachers will not be sufficiently prepared to make substantive changes to pedagogy.

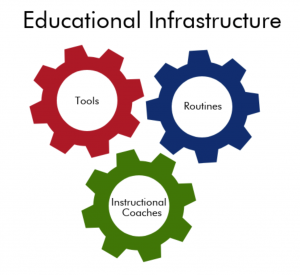

At Mill River Unified Union School District (MRUUSD), intentional educational infrastructure is leveraged to build teacher understanding of proficiency-based learning so as to ensure equitable outcomes for students. A district-wide teacher learning system supports our ongoing effort to implement PBL practices K-12. Making up this “educational infrastructure” are several key elements, including: instructional coaches, collaborative work time, and curriculum tools.

Instructional Coaches

The use of instructional coaches has become generally ubiquitous in schools. However, the nature of the coach’s role is certainly not the same everywhere. Instructional coaches are an essential resource to help move teachers forward with any given reform and to act as sensemakers and brokers to articulate policy for teacher consumption. Coaches can help teachers to understand the nuances of any given reform, such as proficiency-based learning, so as to translate it in a way that is applicable to the classroom. Historically, instructional coaches work with individual teachers using “coaching cycles” to help improve instruction. For instance, a coach might observe a teacher over the course of a few sessions and provide feedback for improvement along the way. However, working with groups of teachers, such as in professional learning communities, helps to increase the pedagogical reach of coaches. Additionally, coaches might curate resources, distill research, and provide advice and guidance to teachers. At MRUUSD, instructional coaches support some teachers on an individual basis through coaching cycles, but much of their work is focused on facilitating professional learning communities and researching best practice.

Collaborative Work Time

Time to talk and work with colleagues is frequently cited by teachers as being crucial to their efforts to put any policy into practice. This can take the form of professional learning communities, vertical teams, grade level teams, inservices, and faculty meetings, to name a few opportunities for collaboration. This time can be used in numerous ways, but the most efficient use of this time is to discuss dilemmas or to share work. Facilitation is needed and should be tight. It can be very easy to be sidetracked onto tangents or get sucked into admiring the problem. Using protocols to collaboratively work through dilemmas is a productive sensemaking practice. Additionally, having teachers share work, such as their learning targets, assessments, student work, and classroom data, can be beneficial for both those sharing and for those reviewing. It is a rarity that other teachers get to see classroom artifacts from another teacher and just as rare for colleagues to provide feedback on those items. Certainly, some time can be spent “doing,” such as actually writing learning targets or assessments, but a focus on collaboration is a powerful lever to build shared understanding and learn from each other. At MRUUSD, we utilize PLCs, grade level time during inservices, and “release days” for each grade level (K-6) and content area (7-12) in both the fall and spring. This time is used to improve shared understanding around proficiency-based learning, be introduced to new tools, and work on certain artifacts (like assessments and curriculum planners). All collaborative work time is tied to the overall work of the district around proficiency-based learning, adding yet another layer of coherence. (See Principle #10 on page 71 in Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education.)

Tools

A variety of tools and frameworks have been provided to teachers to assist in their pedagogical remodeling efforts. A number of documents and visuals were crafted at the school and district level to assist with teacher sensemaking regarding different aspects of proficiency-based learning. One such tool aimed at helping teachers was the “Learning Map,” which is essentially a unit plan template, but with a proficiency bent. The Learning Map provides a way to align all aspects of curriculum, instruction, and assessment in a concise one-page document. Essentially, this template lays out a framework to organize the intentional alignment of instruction, homework, formative assessments, remediation, summative assessments, and reassessments. Coherence and alignment are central to building a functional proficiency-based system of learning. Tools help provide structure for organizing curriculum, instruction, and assessment in addition to increasing a shared understanding of the system as a whole.

An intentionally designed educational infrastructure is a critical element of implementing proficiency-based learning — or any reform, for that matter. All components should work in concert to support a coherent vision of instruction, which was discussed in the previous blog post. Although every school and district is different and so the specifics of the educational infrastructure will vary, a focus on building teacher capacity must undergird everything.

Read the Entire Series:

- Part 1 – Transparency: Operating with a Clear Instructional Vision to Put Policy into Practice

- Part 2 – Supporting Teachers with Making Sense of Proficiency-Based Learning

- Part 3 – Providing Flexible Pathways and Personalized Learning Options for All Students

Andrew Jones is the director of curriculum for Mill River Unified Union School District (MRUUSD) in North Clarendon, Vermont. Twitter: @AlpinistAndrew