Teachers are Managers – So Let’s Give Them the Tools to Manage

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post originally appeared at the Christensen Institute on January 24, 2017.

Good management is hard. Typically, employees grow into manager roles over time. In most industries, employees must first prove themselves effective at their own job; then, they may take on some administrative duties; and only much later do leaders oversee large groups of employees and become responsible for motivating, training, and retaining them.

But two major institutions buck this trend: our schools and our military. In both, newly minted young professionals are asked to take on management roles from the very start. And surpassing even the number of direct reports young military officers oversee, teachers must manage upwards of 30 people the moment they set foot in school: their students.

For any manager, numbers like these are daunting—and having the right systems in place to manage effectively can make all the difference. Good managers motivate and inspire; they move their charges forward toward individual and shared goals; they create structures that provide predictability; and they provide feedback that helps their employees improve over time. And amidst all of this, workplaces are changing and management practices have to adapt alongside them.

As theories of effective management have continued to evolve in the 21st century, teachers—some of our most unsung and overworked mangers—stand to benefit from developments in management science. This begs the question: how might teachers borrow from promising management practices in our country’s top companies?

In a new playbook out this week, our Adjunct Fellow Heather Staker tackles this question. “How to Create Higher Performing, Happier Classrooms in 7 Moves: A Playbook for Teachers” looks at vanguard management practices that are making their way into exciting new classroom models. The playbook summarizes findings from a yearlong pilot project in the San Francisco Bay Area. The project, led by Mallory Dwinal, David Richards, and Jennifer Wu, looked systematically at the structures and processes that high-performing managers at cutting-edge companies like Google, Zappos, and Geico have put into place to create their dynamic cultures. The researchers chose their target companies by consulting Glassdoor’s “Best Places to Work” list, case studies from Harvard Business School, and analyst reports.

What are managers at these firms doing right?

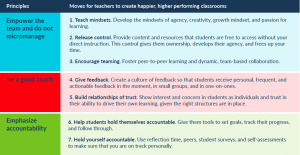

According to their research, the team members concluded that top managers do three things extremely well: (1) They empower their team and do not micromanage; (2) they are good coaches; and (3) they emphasize accountability—both among their employees and of themselves. With these lessons in mind, the research team set about working directly with a cohort of educators at three pilot sites throughout the Bay Area to integrate these same principles into their classroom practices.

In many ways, this was a task in translation: students are not employees, and how schools define success and productivity can vary widely from corporations’ goals. But teaching and management share the same task of shepherding diverse groups of humans to improve and succeed along leading indicators, like satisfaction and engagement, and lagging indicators, like productivity and academic outcomes. In the end, taken together, the pilots revealed seven discrete classroom moves that can help teachers leverage effective management to inspire and support their students.

Within each of these categories, teachers participating in the pilot took different strides in adjusting their practices. For example, Kelly Kosuga, founding math teacher at Cindy Avitia High School, gradually released control to her students by slowly increasing the length of the work sprints. At the start, Kelly used three 25-minute work sprints and set specific times for quizzes. As students got used to the system and built endurance, she lengthened the work sprints to 35 minutes each. She also let students choose when to take quizzes during the work sprints.

By the end of the pilot, though, students were productive for long stretches of time. The researchers heard mostly math speak in the conversations, and they saw students helping each other and doing problems together on the whiteboard. Kelly no longer had to run around attending to students’ needs and could be proactive about giving feedback to the right student in the right way.

By relinquishing some control through a different cadence of independent work, Kosuga could empower her students to drive their own learning. She, in turn, could free up time to teach at the top her craft. Moves like these can lead to higher student and teacher satisfaction rates alike.

This new playbook is chock-full of tactical shifts like these. “Good management,” like “good teaching,” can sound like catchphrases. But at the end of the day, both are collections of practices and processes that shape how humans interact and make progress. Staker’s playbook breaks these practices and processes down. It offers actionable moves for any teacher looking to embolden his students to new heights.

See also:

- Education Innovation in 2017: 4 Personalized Learning Trends to Watch

- Should Instructional Choice Trump School Choice?

- Mastery Motivates Students: “No Way” vs. “Not Yet”

Julia researches innovative policies and practices in K-12 education, with a focus on competency based education policies, blended learning models, and initiatives to increase students’ social capital.