The Rhetoric and the Reality of Student Outcomes in Competency-Based Schools

CompetencyWorks Blog

The exploration of the rhetoric and the reality of student outcomes is a fascinating topic. We use the rhetoric of “college and career ready,” but few states and districts have actually taken the time to clarify what that means, how they will know if students reach it, and actually updated their graduation requirements to reflect it. Thus, we have a gap between the rhetoric and the reality of what we expect for our students.

In fact, all eyes are on Maine as they struggle with whether they believe that their districts and schools can learn and build the capacity to help all students be proficient upon graduation or whether they are going to lower expectations for adults and students. It’s much easier to have graduation requirements be based on a number of time-based credits and perhaps add in a service learning project for good measure than it is to actually make an equitable system that is so responsive, it begins to help students in elementary and middle school build the skills they need for more advanced work in high schools. Imagine systems that are organized so that only the new transfer students are entering high school with gaps in knowledge!

It also makes a difference if the graduation requirements are just academics at the level of comprehension or whether the district has committed to helping students build the higher order skills needed to apply knowledge. One aspect of competency-based education is just that – the ability to transfer knowledge and skills to new contexts. Thus, one way of thinking about competency-based education is as a system of deeper learning.

Finally, in districts that have engaged communities, parents, and students in the visioning process of what they want for their students and schools, other expectations are raised: well-being, lifelong learning, and self-directed learning. These are all concepts trying to capture what it means to have our teens prepared for the transition to adulthood when they graduate.

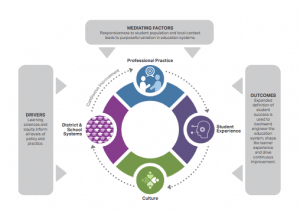

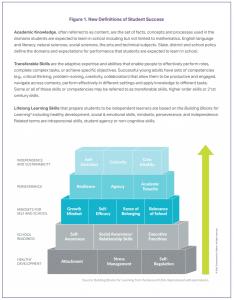

Thus, in the paper Levers and Logic Models, we included all three: academic knowledge, transferable skills and lifelong learning skills.

Each of these have implications for how systems and schools are designed as well as for the instruction, assessment, and learning experiences. For students to develop all those skills included in the building blocks of learning, they need a chance to understand the skills (transparency), practice, and receive coaching and more opportunity for practice. In order to build transferable skills, students need to have opportunity to apply the skills, preferably in authentic real-world and interdisciplinary problems. This requires them to decide which knowledge and skills to apply. In order to do this, districts and schools need to have schedules, community partnerships, and knowledge of project-based instructional design, and performance-based assessments. Finally, for all students to build the academic knowledge, they need to have options for pursuing college and careers. Districts and schools need to be able to meet students where they are, help them fill gaps, and have flexibility in the amount of support and time they need to be successful.

As you read Levers and Logic Models (and as I recommended, don’t try to do it in one sitting or even by yourself; invite colleagues to read and discuss it together), think about the following:

- What does your district and school espouse as the student outcomes? What language is used and how clearly is it defined?

- What are the actual student outcomes as defined by policy and by practice? What skills do students have when they graduate?

- If you wanted to align your school or district around the three sets of student outcomes – academic knowledge, transferable skills, and lifelong learning skills – what would you want to change?

See also: