The Trouble with Prescriptive Policies When Paradigms are Shifting

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the fourth post in the series Reaching the Tipping Point: Insights on Advancing Competency Education in New England. For a more in-depth look at this issue, join David Ruff of Great Schools Partnership and Paul Leather of New Hampshire Department of Education on January 11th for a CompetencyWorks webinar to explore K-12 competency-based education policy and practice across five New England states. Register here.

How can a state bring about a much-needed change when the only way to ensure effective implementation is for educators to want to make the change?

This is what some might called the paradigm-changing policy paradox shared by the New England states and most states across our country. This tongue-twisting, profoundly complex paradox is created because of two dynamics. First, given that competency education requires a paradigm shift or a change in values and assumptions, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to implement effectively without educators embracing those values. When the policies and practices of competency education are placed upon the old values of fixed mindsets and compliant students, classrooms become overwhelmed by linearity and checklists as students tediously climb a ladder of standards. It is very difficult to mandate or require people to believe differently or do something they don’t think is valuable. There has to be an opportunity to engage, reflect, and learn. Second, the states in New England (similar to most states across the country) value local control and are resistant to policies or regulations that feel like a mandate. Thus, prescriptive policies are unlikely to engage districts, schools, and educators and may even produce substantial pushback.

Given that it is impossible to mandate that people accept new values and beliefs, state policy to advance competency education will not immediately translate to transformation of the education system, regardless of how bold, intricate, or high-leverage it is. What are state policymakers to do? How can they drive toward a new education system while not actually mandating that any school change? If competency education is more easily and effectively implemented by educators who have come to their own conclusion that it is needed, how do you engage districts and schools through state policy to want to convert?

Given that it is impossible to mandate that people accept new values and beliefs, state policy to advance competency education will not immediately translate to transformation of the education system, regardless of how bold, intricate, or high-leverage it is. What are state policymakers to do? How can they drive toward a new education system while not actually mandating that any school change? If competency education is more easily and effectively implemented by educators who have come to their own conclusion that it is needed, how do you engage districts and schools through state policy to want to convert?

Thus, states are challenged to find ways to engage districts in the learning that it is needed to implement competency-based education. (By the way, this same paradox challenges districts, principals, and teachers as they seek to engage and motivate school leaders, other teachers, and students).

Policy Features and Capacity Needs

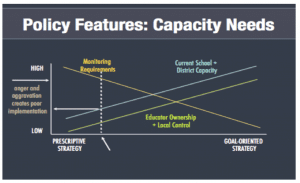

Great Schools Partnership’s David Ruff offers an insightful analysis regarding the tradeoffs between prescriptive policies as compared to goal-oriented strategies that can help to resolve this paradox. If a state uses a prescriptive strategy, the top-down approach is unlikely to generate the deep commitment, shared vision, or the sense of empowerment that is so necessary for the cultural foundation of competency education. The weakness in this strategy is that the districts and schools are unlikely to build the needed capacity unless they have determined that competency education is valuable based on their own interests. Furthermore, state monitoring requirements are likely to aggravate districts and generate distrust. Thus, prescription and monitoring is unlikely to generate the transition to competency education.

In comparison, a goal-oriented strategy that outlines a powerful vision and clear outcomes replaces monitoring with a complementary capacity-building effort to accelerate high-quality implementation. Without capacity building, districts are left to reinvent the wheel themselves, some producing dramatic innovations, while many will be burdened and frustrated by repeated trial and error. Similarly, in a goal-oriented strategy, innovation is likely to produce a variety of interpretations, approaches, and models of how to reach the goal. States will need to employ strategies to co-design new policies and construct the elements of the statewide systems to tap into the local expertise and ensure that they can accommodate the different models.

Each of the New England states featured in our latest report has tried to navigate this paradox in different ways. On one side of the continuum is Rhode Island, with a suite of prescribed practices; on the other are Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire, with more goal-oriented strategies. The theory of change is relatively similar among the states relying on a goal-oriented approach, although the specific mix of activities and efforts vary.

Rhode Island: A Case Study in Prescriptive Policy

Before exploring the goal-oriented strategies, it is valuable to reflect upon Rhode Island’s road to proficiency-based education. Like Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, Rhode Island established a proficiency-based diploma. However, their approach has been much more prescriptive. Rhode Island’s strategy for reaching a proficiency-based system has been through a broad set of requirements for secondary schools, introduced through the Board of Education’s regulations. The practices are primarily organized around multiple mechanisms for determining graduation-ready proficiency, including twenty credits, a performance-based assessment such as a portfolio or exhibition, personalized educational experiences, and responses to needs of students who are below grade level or learning at a slower pace.

Given that few Rhode Island districts to date have embraced proficiency-based learning beyond those practices required in high school, this approach raises the question of whether proficiency-based learning can in fact be catalyzed through precise regulations. Rhode Island’s high schools describe themselves as proficiency-based given the inclusion of performance-based assessments in the diploma requirements. Many have built capacity around personalizing learning plans, performance-based assessments, portfolios, and exhibitions. Yet, few have put into place more than the practices required by the policy.

Goal-Oriented Theories of Change in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine

Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont all use a goal-oriented theory of change, although there is a great deal of variation across the states.

New Hampshire’s strategy starts with a belief that innovation takes place at the local level, drawing upon co-design strategies to build new systems such as graduation competencies and a new accountability system. It also emphasizes that in order to help students learn, schools need new capacities and teachers must be supported in building their skills. A NH Network Platform offers personalized professional development and the Performance Assessment for Competency Education (PACE) initiative is supporting teachers to create and use performance-based assessments that will allow students to engage in richer tasks and build higher order skills.

Vermont’s comprehensive policy of personalization, proficiency-based diplomas, and flexible pathways is complemented by a comprehensive support strategy in which every supervisory union will have the opportunity to train a team in the Great Schools Partnership model. Work groups are being developed to address critical issues in creating the new system.

Maine initially provided an opportunity for districts to train with the Reinventing Schools Coalition. After the policy establishing a proficiency-based diploma and standards-based system was introduced, the Department of Education created a district self-assessment process that has informed technical assistance provided by the Department of Education and allowed districts to set flexible implementation timelines.

For more insights in advancing K-12 competency-based education, download the full report.

Read the Entire Series:

Post #1 – Reaching the Tipping Point: Insights on Advancing Competency Education in New England

Post #2 – The Every Student Succeeds Act: A Catalyst for Competency Education at Scale?

Post #3 – Five Drivers of Transformation in New England States