Transitioning and Sustaining Competency-Based Education During School Closures

CompetencyWorks Blog

South Bronx Community Charter High School (SBC) launched in 2016 with a strong competency-based education approach, as described in the first post in this series. The school’s executive director, John Clemente, shared some of SBC’s structures and strategies that led to a relatively smooth transition to remote learning, despite being located in the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

South Bronx Community Charter High School (SBC) launched in 2016 with a strong competency-based education approach, as described in the first post in this series. The school’s executive director, John Clemente, shared some of SBC’s structures and strategies that led to a relatively smooth transition to remote learning, despite being located in the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

He emphasized that the school “had some advantages” for the transition. These advantages were particularly valuable in the South Bronx, where the pandemic hit hard and affected many staff members and students’ families. SBC was already a one-to-one school, with every student having a device. The school also had a learning management system in place that staff, students, and families were already very accustomed to using for accessing assignments, submitting completed work, and reporting progress. In these areas, SBC was “ready to shift on day one.” Just like at most schools, teachers and students needed to learn to use videoconferencing software for teaching and learning, but they were able to continue much of their pre-pandemic work with below-average disruption.

Sustaining Personal Connections Remotely

Clemente believes that students’ connection to their advisor before and during the pandemic was a major reason that so many students continued strong engagement with the school during remote learning. All students belong to an advisory group where they receive support from two adults—a teacher and a learning coach. The group stays together for all four years of high school and meets daily, focusing on social-emotional support, college and career preparation, and identity and leadership development.

In the first few weeks of remote learning, advisors called each of their students daily, sometimes multiple times per day. They discussed not only how classes were going but also how the student and their family were doing. As in many schools with strong advisory systems, almost all SBC staff serve as advisors, not just classroom teachers. This permits smaller advisory sizes of about eight students per advisor, which lightens the load for advisors who are trying to have individual phone calls with each of their students daily.

While SBC staff are troubled by their drop in attendance, from 90% before the pandemic to about 82% now, this was a substantially lower decline than reported for many other districts. The school has a robust definition of what counts as attendance that includes checking in with the advisor, participating in some synchronous and asynchronous activities, and engaging in school work. Clemente mentioned a study showing that students who want to misrepresent their attendance have found inventive ways to appear to be participating in synchronous activities. One key solution to sustaining student engagement is maintaining deeper connections, and having students know that they’ll be having a meaningful conversation with their advisor.

Structuring Learning from a Distance

Another schoolwide strategy that complemented this approach during the initial weeks of remote learning was that all teachers created a group lesson that was 10 minutes long—and not longer—for each scheduled meeting of the course. Students were encouraged to attend the lesson synchronously, in order to see the teacher and fellow students, but it was also recorded for students to view later as needed. This left teachers more time to connect with students one-on-one or in small groups, and it kept them from needing to present the same content multiple times if they had multiple sections of the same course. It also left students more time to do follow-up work and helped them establish routines. “It was very successful,” Clemente said, “and the teachers were happy. Usually they question everything, but there was so much going on at once that they just said ‘great.’”

SBC is usually very project-based, but during the pandemic “some of the work has become somewhat more bite-sized than it ordinarly would be,” Clemente explained. “Teachers are using that as a way to make sure they’re not losing kids” since they can’t do the usual extensive check-ins and formative assessment or maintain the buzz and momentum that a daily face-to-face classroom permits.

Despite those challenges, they have managed to continue or adapt some of their projects. For example, one of SBC’s annual career readiness projects culminates with students writing resumes in an area of career interest. Students are grouped by industry and interviewed by an outside professional who works in that industry. The professional selects one student from the group who would be their top choice to hire, based on their resume and interview performance. Then the group debriefs about each student’s interview, and they discuss job skills relevant to the industry. In past years, some professionals have become ongoing mentors for the selected student or others in the group.

Before schools closed, SBC had scheduled 20 professionals from across New York City to attend the event. When meeting in person became impossible, the event was held virtually, starting with a large-group gathering and then smaller-group breakout rooms to do mock interviews and debriefs. SBC’s projects usually last from a few weeks to two months, are interdisciplinary, and always require a culminating experience and a product for a public audience. “That’s a demand we place on our staff,” Clemente explained. “It’s a mindset shift. The product can’t be just for the teacher’s eyes. It needs to have some application or interest outside the four walls of the school.”

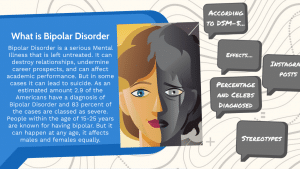

Products from another terrific recent project—the Eleventh Grade Mental Health Interdisciplinary Project (MHIP)—are now available on the school’s website. The introduction says, “The MHIP challenged scholars to focus on a mental health disorder and develop a creative project to display that will showcase the important elements of the disorder. Scholars created podcasts, comic strips, magazines, posters and much more to increase awareness of their mental health disorder. Check them out! Also follow us on Instagram for daily mental health posts.” The web page describes the project kickoff, introduces 19 student group projects, and links to their final products.

Assessment has not changed substantively during remote learning, as the school has always relied primarily on writing and research projects. Written tests are infrequent, because they’re seen as not the best way for students to demonstrate the skills that the school is mostly trying to evaluate. Over time the school has developed competency-based rubrics that teachers can customize to specific student projects. But the school is also being flexible with assessment and providing accommodations as needed, recognizing that the pandemic has added many challenges.

Graduation and Beyond

This year marks SBC’s first graduation, and when we spoke they were still scheming about exciting plans for an online event and featuring pictures or videos of students prominently in prime city locations. They also created a schoolwide event where seniors made Tik-Tok videos to announce their post-graduation plans, including lots of college announcements. The seniors (and everyone else) are of course disappointed about not being able to make the announcements and hold graduation in person, so the school is trying to generate as much excitement and ceremony as possible.

This year marks SBC’s first graduation, and when we spoke they were still scheming about exciting plans for an online event and featuring pictures or videos of students prominently in prime city locations. They also created a schoolwide event where seniors made Tik-Tok videos to announce their post-graduation plans, including lots of college announcements. The seniors (and everyone else) are of course disappointed about not being able to make the announcements and hold graduation in person, so the school is trying to generate as much excitement and ceremony as possible.

With so much uncertainty about what conditions will be in the fall, the school is facing the tremendous challenge of simultaneously preparing for a schedule that is all virtual, partly virtual, or all on campus. They’re discussing the possibility of having students work at home one day every week, or two days per month, even if conditions make coming back to school full-time possible. That would enable more collaboration among teachers to support interdisciplinary projects and other school development goals, and it would give students an opportunity to do work-based learning and off-campus projects related to their interests. It’s a testament to the school’s leadership and vision that even during the current crisis they’re developing ideas for innovations to advance the school’s goals after the pandemic is under control.

Learn More

- Competency Frameworks and Content Selection at South Bronx Community Charter

- A Deeper Dive into the EPIC North Design

- Virtual Youth Summit Supports Student Agency and Community-Building During COVID-19 School Closures

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.