VOICES – Lisa Simms on Leading and Sustaining Innovation

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the sixth post in a ten-part series that aims to make concepts, themes, and strategies described in the Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing, and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education report accessible and transferable. Links to the other articles in the series are at the end of this post.

This is the sixth post in a ten-part series that aims to make concepts, themes, and strategies described in the Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing, and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education report accessible and transferable. Links to the other articles in the series are at the end of this post.

“Competency-based districts and schools are innovative at their core. Educators are at the forefront of innovation, leading the way as they test and share new practices. But, it is a mistake to think about innovators as lone actors or rogue agents of change. Innovators are collaborative practitioners focused on trying, testing and growing new ideas that improve student learning and support school improvement.” – Moving Toward Mastery, p. 48

“Creating a culture of innovation” gets talked about a lot in competency-based education. Almost everyone can agree that implementing dramatic changes in education at all levels requires that everyone, from students to superintendents to state leaders, be willing and able to try, test, and refine new ways of working. What’s sometimes harder to understand is how a “culture of innovation” actually happens. As I listen to teachers and leaders reflect on challenges in their work and as I reflect on my own leadership in the field, here are some questions that come to mind for which there are no easy or clear answers:

How do leaders actually create environments in which people can innovate well? How can leaders balance the need for innovation with the pressures for performance? In what ways does innovation look different (and require different leadership and structures and activities) in early-stage endeavors compared to late-stage ones? What does it look like to sustain innovation over time?

To help answer these questions, I spoke with Lisa Simms. Lisa is a founding design team member and current principal at Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design. DSISD opened its doors in fall of 2015, offering competency-based and project-based learning in early college pathways. In this post, Lisa reflects on what it means to lead for innovation in the fourth year of a new competency-based high school: how she supports teachers to innovate and stay the course as they prepare to graduate their founding class.

How do you lead for innovation?

To start, I asked Lisa what she does in her role as principal to enable teachers to innovate. Specifically, I asked her to reflect on her leadership strategies for sustaining innovation in year four of the school buildout. These were the three big things I heard:

- Listen, then lead. “Teachers need to have voice. If we’re going to own innovation in our own way, we have to honor the expertise in the room. Then sometimes, I need the stage.”

- Hold the vision. “I keep our vision in front of us. There is nothing we do that is not aligned to our vision. At this point teachers own it, too. They will push back against things that are not aligned to our vision and the core drivers of our school model.”

- Manage (and embrace) the conflict that comes with innovation. “We have to hold our shared agreements in front of us. This year we normed on our agreements at the beginning of the year, like we always do. But after tough conversations this fall I realized that we would need to re-norm mid-year. We are in the middle of this now. I am asking teachers to dig deep, to go through the agreements that were written by ten founding teachers four years ago, evaluate them, and help create a set that is relevant to us now.” Lisa added that conflict — even very difficult conflict — can be powerful for team building and learning. “Late in the fall we had some very difficult conflict. It was almost a mutiny. And, after team reflection and team building, it was one of the best things that could have happened to us.”

How do you balance the need for innovation with the pressures for performance?

DSISD hires teachers with a passion and dedication to interdisciplinary project-based learning and meeting students where they are. Even though DSISD procures autonomies through Colorado’s Innovation Schools Act to be able to define their own curriculum, the very real pressures for performance — ensuring that students are proficient on standardized tests and score well on the SAT or ACT — can seem to run counter to the commitments that brought teachers to DSISD. In our conversation, Lisa reflected on the ways she has helped her teachers to balance the pressure for performance with the spirit of innovation that drives them.

“I started the year with my team by talking about Simon Sinek’s golden circle. At DSISD, our ‘why’ is clear. We share a purpose, and in our school we are all on the same page about the essence of our true purpose, grounded in our shared core beliefs. And, our ‘what’ is clear. The goals we are measured by, which include but aren’t limited to standardized assessments and SATs and others, these are things we cannot argue with. If we don’t prepare kids to to achieve these outcomes, we’re negligent. So what we need to be protective of as innovators is our ‘how.’ How we get to those outcomes and toward our why. We get to generate and execute our own strategies, and control our own narrative.”

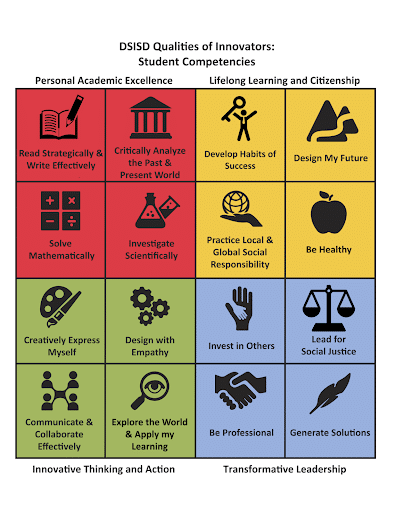

What Lisa and her team have done is create a world of “both and.” They are saying yes, we will make sure our students are achieving by standard measures, and then some. (See the DSISD Student Competencies model (Figure 1) below for an idea about their broader definition of success). And, getting to these outcomes does not have to mean falling in lock step with traditional approaches to teaching and learning. When tensions between compliance and innovation inevitably arise, the team regrounds in their purpose and collaboratively finds creative ways to stay true to who they are.

In what ways does innovation look different in DSISD’s fourth year compared to its first?

Innovating at the very beginning of a new school is all about building. It’s a period of invention. Four years later, innovation means something different. It means adjusting, streamlining, and aligning. While it does not mean the end of new ideas, it does mean fitting new ideas into a much larger picture and a more complex system. Lisa described it this way: “For the last four years we have been building the plane while flying it. Now that we’re at full buildout, it’s time to assess the plane. Is our compass working? Do we have the right parts? Are we flying in the right direction? What we’re NOT going to do is start building a boat, now that we’ve built a plane.”

I asked Lisa what it looks and feels like to lead her staff through this process. After all, Lisa and her leadership team have always hired teachers who align to the DSISD vision and culture, including having a proclivity for challenging the status quo and testing new ideas. She said, “Our staff looks totally different than it did when we started. We have our ‘OGs’ (founding members) and our new teachers, who weren’t there at the beginning and might not have the full perspective on where we’ve come from and what we’ve learned along the way. My job now is to merge the core beliefs of the founding team with the core beliefs of the new staff and generate a new identity with everybody. Who are we NOW?” In other words, leading a team of newbies and founding members in year four of a school buildout means keeping the founding narrative and vision alive, while continually grounding the whole team in a common understanding of where the school is today: approaching maturity, working to sustain an innovative model.

What does it look like to sustain innovation over time?

I wanted to dig into this idea of “sustaining an innovative model” a little more deeply, so I asked Lisa the following question. “In year four, what does it look like for a teacher to try and test a new idea? Is the era of new ideas over?” She shared a story that illustrates what innovation looks like at DSISD today.

“In the fall our teachers took a trip to William Smith High School in Aurora, Colorado. They came back raring to go. They wanted to blow up our schedule and do interdisciplinary, cross-content projects. At first, with an Expeditionary Learning background myself, I was all over it, but upon reflection I realized what the lift would be, especially with limited resources. I had to slow the momentum. Not kill it, just help us focus and bring the new ideas down to earth. How can we do it incrementally? A mentor of mine introduced me to this idea of the trim tab. A trim tab is a tiny piece attached to a boat’s rudder, and it is the piece that initiates the boat’s turn. How do you change a school? You start with small, small incremental changes the way a trim tab starts a whole ship’s turn with a tiny movement. So that’s the idea I used with teachers after William Smith. How can we start the small changes that can get us toward that bigger vision? The same teachers got together and created a presentation about what could be possible for scheduling next year. I was totally open to it, and two of those teachers are piloting a cross-content project right now. They know they have my support; they also know that with autonomy comes responsibility and that we have to get there by starting small.”

Read the entire series:

- Introducing Moving Toward Mastery

- Entry Points: Moving Toward Equity-Oriented Practice

- Voices: Developing Teacher Mindsets

- Entry Points: Moving Toward Learner-Centered Practice

- Actions: Ideas and Strategies for School Leaders

About the Author

Katherine Casey is Founder and Principal of Katherine Casey Consulting, an independent organization focused on innovation, personalized and competency-based school design, and research and development. Katherine was a founding Director of the Imaginarium Innovation Lab in Denver Public Schools, supporting a portfolio of almost 30 schools across Denver and spearheading the Lab’s research and development activity. Katherine was a founding design team member at the Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, Denver’s first competency-based high school. Prior to her time in Denver, Katherine worked in leadership development, philanthropy, public affairs and higher education. She received her BA from Stanford University and her Doctorate in Education Leadership from Harvard University.

Katherine Casey is Founder and Principal of Katherine Casey Consulting, an independent organization focused on innovation, personalized and competency-based school design, and research and development. Katherine was a founding Director of the Imaginarium Innovation Lab in Denver Public Schools, supporting a portfolio of almost 30 schools across Denver and spearheading the Lab’s research and development activity. Katherine was a founding design team member at the Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, Denver’s first competency-based high school. Prior to her time in Denver, Katherine worked in leadership development, philanthropy, public affairs and higher education. She received her BA from Stanford University and her Doctorate in Education Leadership from Harvard University.