Voices of Indigenous Educators Series: “How do we prepare them? Sure, academics play a part, but holistic wellness does too.” – Sage Fast Dog

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post is based on an interview in April 2024 with Sage Fast Dog, Founder and Head of School at Wak̇aŋyeja Ki Ṫokeyaḣc̄i Lak̇ot̄a Immersion School in South Dakota.

Mitakuyapi, PejiHota Sunka Luzahan emaciyab, cante wasteya ciyunzap pi na SicanguCo ta Wakanyeja Ki Tokeyahci wowasi ecamu yelo wounspe itancan el hemaca. Lakota woglakapi hecel yelo.

My name is Sage Fast Dog, and today, I greet you with a good heart. I’m Sicangu Co, Wak̇aŋyeja Ki Ṫokeyaḣc̄i Head of School. I’m charged with trying to transform education in Rosebud. I took this job because it is part of my passion to transform our community into an area that’s led in the direction our community wants it to go. What I’m doing is very purposeful, and I’m very proud to be able to share it with my family.

Our school name is Wak̇aŋyeja Ki Ṫokeyaḣc̄i. It means Children First Learning Center. This philosophy is very old, this philosophy is not new. This is how Lakota thought about their children and how they prepared and planned with them. Our children are the best gift, and these parents were gifted with bundles of joy and a huge responsibility. Sure, it comes with headaches and worries when seeking to raise kids to adults. Then it comes with heartbreaks because your kids leave the house and don’t listen to you. That’s when you get to be in your mom and dad’s shoes.

Even as a parent, because I’m a parent of the school, it feels more purposeful and connected, knowing there’s a school designed to prepare our kids for the future. It validates that Indigenous people in the world have always planned for their kids’ future. For 150-plus years, we were forced to join a system centered on a foreign society or culture, and we went with it. Their process was to take kids away forcibly, take language away forcibly, take customs away forcibly, and they were backed by federal policies. Now, we’re left with communities with little understanding of how we used to live – our way of life. I’m talking about the thousands of hours it took to master crafts that happened naturally in communities, like making a bow and arrows and learning how to hunt safely.

Now, how will our kids be prepared? We’re still dependent on charity to bring us electricity and the local grocery stores to bring us food. How is that independence? We traded our economy, where we hunted and traded, and made our own homes from a hide with the knowledge to sustain the elements in South Dakota, Montana, Nebraska, Minnesota, and even up to Canada. We traded the knowledge we were born into for the United States public school system.

Ehanni Lakota wicoye wounspe ki lila hci yukan mila hanska oyate reservation kagapi na wasicu owayawa kagapi canna Anpetu ki le oyate ki lakolyapi conala okihi ca Wakanyeja ki Tokeyahci unkagab pelo.

The public school system has had its turn. Wak̇aŋyeja Ki Ṫokeyaḣc̄i is a school that says “That’s enough.” We have sixty years of recorded data that says we have a 68% graduation rate, and a lot of our tribal members are in a state penitentiary. They’re not job-ready, and our community has a high social welfare system. Enough is enough.

What is the opportunity for learning that you are running towards? Why is this important in your community now?

I’m most excited about learning how to operate a community-based school independently. We’re an official Rosebud Sioux Tribe community-based school, and I’m learning how to take opportunities to teach culturally. We don’t have to educate our children in traditional Western ways. Sure, we have some standards and concepts that need to be mastered, but we also have to understand how the world works.

If “children first” is our first thought, how do we prepare them for the future? Sure, academics play a part, but holistic wellness does too. How do we keep our kids sustained in who they are, how they care for each other, how to keep their voices, and how we can be secure no matter where they go? To walk away from that wouldn’t be very wise, and it wouldn’t show compassion to our grandmothers who sacrificed themselves so we could walk across the fire. If we walk away from our culture, we can’t call ourselves Sicangu anymore. Even though it’s hard, we still have to push forward. We must think about where we will be 175 years from now. We’re only five years in, and it feels like we’re getting smashed and gobbled up by all of these monsters, called “iya,” from the school system. I won’t be stagnant; I’ll keep moving outside of the system, helping people inside understand what I’m doing.

Together, we’re figuring out how to get all that knowledge from our grandfathers and grandmothers. That’s our problem-solving. How do we have all this land here, and yet we’re starving? How are we poor with all the land our tribe has? It shouldn’t be that way.

Who is helping you with this work? Where are your ideas coming from?

Who is helping you with this work? Where are your ideas coming from?

First off, my staff is directly helping me, every day. They’re all community-enrolled members. Half of them are my former middle school students, and they’re all speaking the language, some fluently. Together, we’re making the path forward.

Of course, the economic development team is helping with the financial part so I don’t have to worry about that, and our board helps us, too, so that I can focus on the daily work. Also, the community helps us. In our neighborhood, we have Sokela ki, unhoused people, who look after us. They help us clean up the field where the kids play, and when I sit and listen to them, they share their pride in what we’re doing. They watch over us and protect our buildings. They make sure there’s no vandalism or break-ins at our school.

From kindergarten up to fifth grade, everyone participates when we harvest buffalo. Relatives and friends come so we all know how to harvest, how to sustain. We’re addressing the problem of knowledge so our relationship with the buffalo isn’t lost. Now we have a group of people still fighting for the buffalo to be here. For us, there’s the nutritious palette but also the teachings and the acknowledgment that the buffalo have a place here on the earth. That’s the original treaty the Lakota hold. It’s with the buffalo and the horse and all the animals here. We have to make sure they stay here. Our original agreement is with the Buffalo Nation for taking care of us. We can think of it as epistemology; when we think about our stories, the Lakota people are the ones with the buffalo. So, if we don’t have the buffalo, we become irrelevant.

When we do our language weekends, the community comes and asks questions. “How is this a school? How are you teaching? Tell me more.” My response is: “I’m just putting it together with what our people talk about.” That inspires them to come to support us or go back to their community and start their own school. That’s how we keep this going.

We know that the work that you’re doing is hard on a lot of levels. It takes a lot of time to achieve the full actualization of your dream. What does this look like and feel like?

Sometimes, I think of myself as that kid who signed up to be on the basketball team and only gets put in for the last 10 seconds. I get on the court and start flying around, trying to prove myself, but if I miss or they steal the ball, the coach sends me back to the bench. Meanwhile, the star player gets the ball stolen 10 times and misses 20 buckets, but he’s still out there. That’s the public school system – 60% graduation rate but still functioning and operating with federal money.

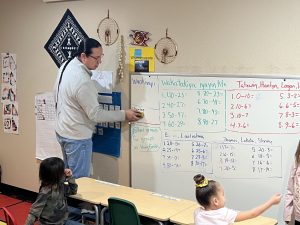

Every week, I slow down and think about all the vocabulary words in the next passage I’m reading to them. What words do they have to learn to make meaning with it? How can they pick up and use those words daily? How do I use them? Where do we go from there and teach them what scientists do with those words? Science is in everything we do. There’s chemistry in preserving buffalo hide, and earth science is what we’re doing when we learn about our water. So we teach them the importance of water with examples like Standing Rock and how it still directly affects us. We tap these trees here for sugar; if we do that, we need to ensure they have good, clean water, the earth to grow, sunshine, and time to heal. So, with the science, they learn Lakota ways too. We need to protect our land.

There’s a lot to think about – that’s why, even though I’m in my principalship program, I’m still teaching. I’ve also taught since the first year the school opened. Even though I have the title, I’m never really the head of school; I’m always teaching. My supervisor tells me, “next year, you can’t do that. You have to be in your spot,” and I think, “We’ll see.” We’re demonstrating to the community we’re not going to wait, we’re going to teach our kids now.

Where do you think you are on the path to that vision? And what are some of the next steps that you plan on taking?

We’re moving forward. Our kids receive instruction daily in the Lakota language. Every day, they interact with a culture keeper of our tribe, who holds so much knowledge for us. Then, we have Grandma and Grandpa come into the school to talk about our history and culture in Lakota. That’s the dream.

When I created this school, I knew I wanted to create a place where I can be Leksi – which means uncle in Lakota. I want to do for my students what an uncle does for his nephews and nieces: to teach, lead, and guide them.

This year we competed in the Lakota Nation Invitational Language Bowl, K-3. They asked, “Toske eyapi teacher Lakota eyapi he?” Which means, “How do you say teacher in Lakota?” And one of my Toska, my nephew, raised his hand, “That one’s easy!” And he slammed his buzzer. He called out so convincing, so powerful, “Tunwin,” meaning “Auntie,” and I responded, “Yes.” And I knew he got it wrong because they were looking for the Lakota translation “teacher,” but for me, we won. We won because my Toska knows his Tunwin is his teacher.

I had to go advocate for my Toska, because what are we judging here? Just vocabulary and literal translation? Or are we looking at what we’re overcoming as a people? That’s the school culture here, we lift up kinship. We call it wotakuye – or kinship – how we talk to one another and how we visit. That’s all you hear from our kids. They call us Tunwin (auntie) and Leksi (uncle), here at school or even at the grocery store.

The other thing is that our kids are able to express to each other when they don’t like something, even when it’s challenging. They’re learning how to sustain their boundaries and values. Seeing that in our school is important because when you say it, people listen. That voice is important. It builds them up. We need to make sure we’re sustaining their identity by listening and recognizing who they are and collectively agreeing how we want to exist in this space. Student autonomy, respect, and consciousness are so important.

Knowing it’s messy and that you’re in a process, can you paint a picture of a moment when you felt it? A moment when you felt or you saw a glimpse of it and said “this is what it will feel like every day.”

Knowing it’s messy and that you’re in a process, can you paint a picture of a moment when you felt it? A moment when you felt or you saw a glimpse of it and said “this is what it will feel like every day.”

Every morning, you’ll hear us singing. They gather up and practice speaking to each other about their weekends and what they have planned. You’ll smell sage burning because the kids will then get the sage and sing as they smudge, as in ceremony. They’ll ask each other how they’re doing, “toske,” and they’ll respond.

We’ll sing the Buffalo Song or the Meadowlark Song when we’re done. The Meadowlark song is significant to us because that’s who we have to be here. We believe we have to be like Meadowlark, who sat on the teepee poles, went down to eat food in the Lakota camp, and learned the Lakota language by being there in community. When Falling Star’s mother fell to the earth and Falling Star was born as an orphan, all the animals decided Meadowlark would raise Falling Star. That’s who we will be; that’s why our logo is Meadowlark and these kids are Falling Star. They’re all fallen stars that have come to us, and we have to be their community and teach them values and Lakota.

That’s what this school is, and as we move forward, how do we bring all of that into school? How do I lift up the young educators? How do I lift up the young food coordinator who’s bringing buffalo and fresh produce to our menu? Ultimately, we need to get to a place where we can be who we are, no matter what.

“Cantematinza” – like Wakanda Forever. We have to be like that; chanting with pride. They don’t have to carry the cultural shame that we were born into. We are Lakota. We are the history of this land.

If you could wave a magic wand and change something, what would it be, and how would that change the trajectory of your work?

I’d put it away. I’d put it away and say, “I’m thankful for what I have right now.”

The only thing I may wish for is that I continue to sustain what I’m thinking already so that I have the strength to overcome what’s coming for me and what’s in front of me so I can continue to build this path. So that the people who are beside me and helping me can continue pushing forward if something happens to me and I go back to my relatives.

Now, I’m not saying that I wish I won’t get Alzheimer’s or anything like that, but I’m saying that I wouldn’t change the experience or the road I’m on. Without those experiences, failures, and opportunities to overcome and make amends, I wouldn’t be where I am.

Of course, transportation and money would be great, but it wouldn’t mean anything if I didn’t have the cante (heart) or the nagi (spirit) to get there.

This interview is part of a series exploring the intersection of Indigenous ways of learning and competency-based education (CBE). Through these conversations with Indigenous educators, the Aurora Institute and the Liber Institute aim to create a space for meaningful storytelling, celebrate resilience and innovation in Indigenous education, and inspire more inclusive, culturally responsive educational approaches.

Images courtesy of Wak̇aŋyeja Ki Ṫokeyaḣc̄i