Equitable Grading Anchors NYC’s New Grading Policy Toolkit

CompetencyWorks Blog

New York City Public Schools signaled important learner-centered shifts in grading practices with its new Grading Policy Toolkit: Grading for Equity, Accuracy, and Social-Emotional Well-being. This post explores the toolkit in more depth as a model of how districts large and small can support the alignment of practice to their visions for equitable learning with practical policy guidance.

The Pandemic Prompts Reflection on the Role of Grading

The pandemic prompted many educators and school and district systems to question the purpose and meaning of grades. As educators and families sought to support learners during disruptions to formal learning and now seek to mitigate the impact of those disruptions, it has become clear that learners are in different places and need targeted support that we can only provide if we understand both the most important learning goals and where a student is in their learning relative to those goals. These are key elements of a CBE system and in fact, many CBE-oriented systems fared relatively better in navigating the challenges of the pandemic.

The New York City Department of Education (NYC DOE) intentionally focused on grading policies as one way to support students as they recover from and adapt to the ongoing pandemic disruptions to the education system. While some pandemic policies were temporary, the grading policy guidance remains as a permanent shift based on lessons that were surfaced or elevated by the pandemic, but were true before, during, and after.

Drawing on Your Innovators in Creating New Policy

NYC’s Competency Collaborative communicates and collaborates regularly with the NYC DOE’s Department of Academic Policy. As a growing, opt-in network of NYC schools, the Competency Collaborative members offer examples of competency-based, student-centered systems, including competency-based grading. Network members are supported with a variety of learning opportunities throughout the school year and summer, including sessions such as how CBE practices can help with not grading students for factors beyond their control. The Competency Collaborative worked with Joe Feldman, author of Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms, which aligns with many competency-based ideas even though it is not explicitly framed as a CBE approach.

When the Academic Policy Team began work on the grading policy, the city’s vision for culturally responsive-sustaining education (CR-SE) and Feldman’s work became key influences. It was natural to learn from the schools already implementing CR-SE that use competency-based practices focused on evidence of student learning.

Mindsets Shifts for Equity, Accuracy, and Social-Emotional Well-being

Joe Feldman reminds us that grading is emotionally charged. Like much of education, it’s a place where our beliefs and experiences are reflected. In a grade, we see the way teachers think about power, motivation, and what makes for a successful student in and beyond school. We see approaches to pedagogy show up in how we grade homework and late work. We see how teachers value various aspects of their courses and curricula. All too often, these disparate factors are mixed together, not clearly articulated, and sometimes even executed without deliberate intent.

The NYC DOE Academic Policy Toolkit starts with the premise that there are many decisions, often invisible, that go into a grading policy. This alone is a shift in thinking. By making visible the choices that adults make about grading, the policy creates a space for educators to have a conversation about the impacts of those choices and how they’re felt by students. Another important premise is that each of these choices, even if seemingly benign, has an outcome that can foster a more or less equitable environment. This is the lens the policy toolkit asks decision-makers to take: what are the decision points in grading and how do they impact equity, accuracy, and the well-being of students?

Beyond this premise, the policy makes one more unspoken truth about grading clear: in our culture, grades serve as both information about what students know and can do AND credentials that open and close doors to next-level opportunities. Teachers feel this oft-unspoken tension all the time. It’s the silent motivation behind bumping up a student’s grade, accepting a pile of late work on the last day of the marking period so that a student can pass, or entering a missing assignment minutes before a big game so an athlete can remain eligible. That pressure is real, and it matters deeply. No educator wants to stand between a student and a scholarship, the next grade, or their dream college program.

The weight of systemic oppression shows up here too: for Black and brown students and other students who have been underserved by our system, a grade might mean even more. The stakes are high, and they are real, and they are felt deeply by students and educators alike. By lifting up this tension, we can begin to have the conversation about what an “equitable” grade looks like. Joe Feldman firmly takes the stance that an equitable grade is an accurate grade. We do students no favors by giving them an inaccurate picture of what they know and can do. Instead, it is incumbent upon us as educators to show students where they are in their learning and make the road to proficiency clear. This is the work of equitable, competency-based grading.

Technical Grading Shifts for Equity, Accuracy, and Social-Emotional Well-being

If we’ve started the deep work of shifting our mindsets about what equitable grading looks like, there remains a nagging question: how do we do it? The policy offers support to educators in implementing equitable grading by sharing out key decision points in crafting a grading policy. Here are a few commitments that take a stance toward equity.

Base Grades on Academic Performance

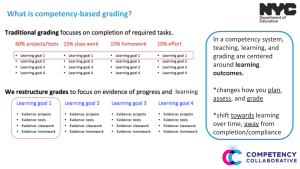

The NYC policy asks all schools to base grades on academic performance, rather than completion or compliance measures.

“After considering a student’s entire body of work in each subject area, schools must award students’ grades primarily based on academic progress and performance. In all courses, including physical education (PE), science labs, and electives, students must be graded based on how well they have learned the subject matter, concepts, content, and skills in that course.”

This shift is a key element of competency-based grading, and is a fundamental mindset shift for traditional educators. Instead of communicating grades by assignment type (homework, classwork, test, project), grades are organized by learning goal (argue with evidence, graph a linear equation). The core premise here is that an equitable grade tells students where they stand on the path to proficiency for the learning goals in the course.

Deeply implementing competency-based schools take this one step further by communicating the grades to students organized by learning goal rather than converting the level of proficiency into traditional grades.

Deeply implementing competency-based schools take this one step further by communicating the grades to students organized by learning goal rather than converting the level of proficiency into traditional grades.

For some schools, this clear communication is one of their primary reasons for moving towards competency-based education. KAPPA International High School tells the story of their student Angelica. “She did everything we asked of her.” She was a star student, receiving top marks in her classes, but when she sat for her Regents (NY’s state graduation tests), she failed them. “We realized we were giving her misinformation,” then-Assistant Principal Andy Claymen shares. They began their shift to competency the next year.

Attendance Can’t Be a Factor in Grading

In the early days of the pandemic, when school was suddenly online and students were grappling with issues from connectivity to illness to trauma, many students had low attendance. Educators went door to door, making sure students were safe, and working to re-connect them to the support net of their school community. Turning in work became secondary, as students’ humanities rose to the fore. In that context, factoring in attendance was cruel. So much about making it to school and completing work was beyond students’ control…but isn’t that always the case? We need to create welcoming learning environments that support engagement. This does not happen by using grades as a tool for compliance.

This way of thinking demands a shift from educators – one that competency-based practitioners have already made – away from thinking of work as a completion measure and towards the idea of work as evidence of learning. It is not about how much work has been done or how long a student has spent in the classroom. Educators and students must work together to develop evidence of students’ learning that supports their receiving a grade at one level of proficiency or another.

In this view, the landscape of assessment is broadened. Maybe a student didn’t turn in a written assignment but gave ample evidence in class discussion of their learning and will have another chance to show what they know during a test or final project. How much evidence of learning does a teacher need to feel confident they can accurately assess a student’s level of understanding? Some competency-based grading policies include this metric, for example saying each learning standard must be assessed three times. This ensures that each assessment is lower stakes, and a student’s grade will not plummet for missing one assessment opportunity. An equitable system provides students with multiple opportunities to learn and practice along with multiple assessment opportunities to demonstrate their learning.

Draw Inspiration from NYC and Get Started

No matter your role or experience level, at CompetencyWorks we hope readers will be encouraged to find actionable takeaways from the blog. Are you a curious teacher in a system not yet talking about competency-based learning? Are you teaching or leading in a system moving towards CBE and equitable grading? Do you work in NYC or another large urban district? Or maybe you are in a tiny rural community? In closing, I offer a few thoughts on potential entry points and encourage you to learn more about the rationale behind these practices.

If you are in a classroom, try an equitable grading move (or two):

- Eliminate participation points or other elements of compliance – only grade evidence of student learning.

- Don’t grade homework, which may be influenced by factors beyond students’ control.

- Offer opportunities for a re-take or revision. Replace the previous grade!

- Say “no” to extra credit.

If you are feeling bold, go bigger!

- Base grades on the 2-3 focus skills you identify for an upcoming unit.

- Say “no” to averaging – If you don’t pass your driver’s test on the first try, you can take it again. And eventually, no one remembers or needs to know that it took multiple tries.

- Reorganize your grade book around the learning goals rather than in traditional categories such as tests, projects, homework, etc.

The Competency Collaborative also has a great resource with more Grading Moves to Try. Whatever moves you try, talk with students about the new approach and get their feedback along the way. Shifts in grading can be a shift in mindset for students, too.

If you are a school or district leader or a teacher leader planning to bring CBE and equitable grading ideas to your school’s leadership team or principal, learn from NYC’s change process. New York City’s new guidance on grading policies is one example of a system-wide reflection resulting in a shift towards more equitable practices.

Putting these guidelines fully into practice invites reflection and action to try new approaches. The more policy and practice align, the more hope we can have for moving our education system toward equity. The NYC process models a spirit of reciprocal responsibility, setting policy that is informed in practice on the ground at the Competency Collaborative schools. As more schools engage with the new equitable grading policy and consider the purpose and the impact grades have on learners, the cycle will continue and hopefully lay the groundwork for continuing shifts in mindset, structures, and pedagogy.

Learn More

- CBE in Practice: Grading

- What Does it REALLY Mean to Do Standards-Based Grading? (Part 1)

- Grading for Equity: A Teacher’s Reflections

Laurie Gagnon is the Aurora Institute’s CompetencyWorks Program Director.