A Mastery-Based Math Teacher’s Journey, Part 2 – Refining Mastery Skills and Assessment Strategies

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second post in a four-part series by Ashley Ferrara about her ongoing journey to develop a mastery-based approach to teaching mathematics. She is a teacher and interim acting assistant principal at the Academy for Software Engineering in New York City, a member school of the Mastery Collaborative.

This is the second post in a four-part series by Ashley Ferrara about her ongoing journey to develop a mastery-based approach to teaching mathematics. She is a teacher and interim acting assistant principal at the Academy for Software Engineering in New York City, a member school of the Mastery Collaborative.

I’m back! I hope you did your homework of thinking about at least two big ideas or topics that repeat throughout the year in your course(s). And by “did,” I mean you thought through it, probably got frustrated, changed your mind 341 times, and then decided to go with your gut. If you didn’t do that, then I’m jealous, because that’s what my experience was like!

In this post, I’m going to talk you through how I took the big topics that repeated themselves in my algebra course (i.e., the three mastery skills I mentioned in the last blog post), added a few more, and started to distribute my content within them. At the time, I was teaching Algebra 1 to high school freshmen. During that year, my co-teacher and I encountered the next challenge on the road to mastery.

We had figured out that most of the mathematics in our algebra curriculum repeats itself, but what were we supposed to do with the “one-hit wonders” that didn’t repeat themselves? Our solution was to create unit-specific mastery skills that addressed all the one-offs. Let me explain with an example of one of the year-long mastery skills and one of the unit-specific mastery skills I formally assessed (i.e., put on the unit test) for Unit 2: Linear and Exponential Functions. For those who want more, the remaining skills from the unit are here.

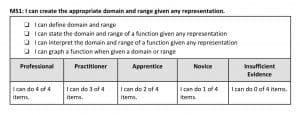

Year-Long Mastery Skill (this was assessed in Unit 2 and in other units)

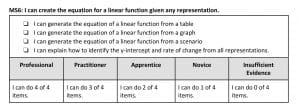

Mastery Skill for the Linear and Exponential Functions Unit (this was assessed only in Unit 2)

My constructive criticism about these skills below is by no means saying “we should have known better.” We didn’t know better, we were trying so hard to figure out how to make this work, and, as my mom always reminded me after a bad breakup, “hindsight is 20/20.” With that said, I’ll share three observations that could have helped me back then and that might help you.

First, the unit-specific skills were born out of my need to make sure I had covered anything that could possibly be on the state exam. At the time, I only felt like something was “covered” when I had explicitly taught and assessed it. This is why the three different representations (table, graph, and scenario) were addressed separately in each skill—which also meant that they were taught separately and assessed separately. What I would like to go back in time and ask myself is, “Does treating each topic like its own unique content help students find the through-line across the unit, year, or even their overall academic experience?”

Second, I want to elaborate on what it looked like to teach each of the unit-specific skills separately. This meant that students were receiving a mini-lesson on how to generate the equation of a linear function from a table and then immediately practicing that skill. Then they’d receive another mini-lesson on how to generate the equation of a linear function from a graph and practice that skill. The only time students were given an opportunity to see and practice content covered in previous classes (also known as spiraling) was if a different representation (e.g., tables instead of graphs) was added at the end of a worksheet. Something I’m wondering is if repeated practice, especially with specific and small skills, helps students with retention and recall weeks or months later when those smaller skills are folded in with many others?

Lastly, I want to dive into what it looked like to assess each part of the unit-specific skills separately. When my students reached the assessment at the end of the unit, they’d see one question for each subskill. This made our Unit Two test so long that it had to be split across two class periods. It was a nine-page packet that required 37 unique answers. Thinking back on that now, I’m amazed that my students actually took the assessment; they were probably complying but not really engaging.

The next blog post explains my evolution to structuring my course around skills that could be assessed repeatedly throughout the year. A few questions for you to reflect on related to this blog post and the next one are:

- What does spiraling look like in your classroom? What would it ideally look like?

- If your course ends in a state exam, how does that impact your decision making around your curriculum?

Sources I referenced for this blog post:

- SY17-18 Semester 1 Mastery Skills

- SY17-18 Semester 2 Mastery Skills

- Unit Two Assessment: Part One

- Unit Two Assessment: Part Two

Learn More:

- A Mastery-Based Math Teacher’s Journey, Part 1 – Initial (mis)Steps and the “Aha!” Moment

- A Mastery-Based Math Teacher’s Journey, Part 3 – Moving Away From “Covering” Everything

- A Mastery-Based Math Teacher’s Journey, Part 4 – Embracing Problem-Solving and Further Refining Mastery Skills

Ashley Ferrara is a founding faculty member at the Academy for Software Engineering (AFSE), a public high school in New York City. She joined AFSE nine years ago and was an Early Career Fellow and Master Teacher with Math for America for seven of those years. After earning a bachelor’s degree in accounting from the University of Connecticut and working with a big-four accounting firm, she earned master’s degrees in mathematics education from Teachers College, Columbia University and educational leadership and administration from Bank Street College of Education. She also graduated from the New York City Department of Education’s Leaders in Education Apprenticeship Program (LEAP).

Ashley Ferrara is a founding faculty member at the Academy for Software Engineering (AFSE), a public high school in New York City. She joined AFSE nine years ago and was an Early Career Fellow and Master Teacher with Math for America for seven of those years. After earning a bachelor’s degree in accounting from the University of Connecticut and working with a big-four accounting firm, she earned master’s degrees in mathematics education from Teachers College, Columbia University and educational leadership and administration from Bank Street College of Education. She also graduated from the New York City Department of Education’s Leaders in Education Apprenticeship Program (LEAP).