A New Framework to IMPACT Building a Defensible Body of Evidence

CompetencyWorks Blog

If you were to analyze student work samples in a body of evidence for students in your school right now (such as in a digital portfolio), what would you typically expect to see? Does the collection of artifacts – the evidence – tell a comprehensive story of each student’s learning? As my colleagues and I have worked with school teams across the country, the question of how to build a defensible body of evidence continues to come up. It comes up when we talk about assessment. It comes up when we talk about grading. And, it comes up when we talk about how to determine whether or not a student has met the requirements for proficiency. A new handbook for professional learning community (PLC) teams with my co-authors Jon Vander Els and Brian Stack addresses these questions by defining and offering a guiding framework to competency-based schools for building an equitable and defensible body of evidence.

A New Framework to IMPACT Building a Defensible Body of Evidence

The phrase “body of evidence” (BOE) might be more familiar to those working in the fields of scientific research, policy-making, or crime scene analysis than to most educators. However, a body of evidence, regardless of the context, always refers to a well-supported collection of information used in defense of a stated claim. Evidence can include data, facts, artifacts, and documentation of methods or processes that lead to making an informed decision, such as whether a student has demonstrated proficiency on the agreed-upon learning expectations (standards, competencies, etc.).

What makes a BOE defensible is that the evidence is of high quality – both valid and reliable – and logically structured in a way that can withstand criticism or challenges. Validity is determined by checking the alignment between the learning expectations and the assessment strategies used to collect the evidence. In other words, the assessment actually evaluates what it says it will evaluate. Reliability is demonstrated when there are clear rules and decision points (such as rubric criteria, scoring guidelines, or annotated exemplars) that support anyone independently reviewing the evidence presented in coming to a similar conclusion.

Here’s an easy way to remember the difference between reliability and validity that I often share with educators: Reliability is like McDonald’s – same menu, same ingredients, same prices every time. Reliability in assessment means that different educators agree on what score to give – same results every time! Validity, however, is not McDonald’s if I’m looking for a healthy, vegetarian meal! An assessment can be reliable in terms of scoring agreement without actually assessing what you think it purports to assess. Validity requires clear alignment with learning expectations.

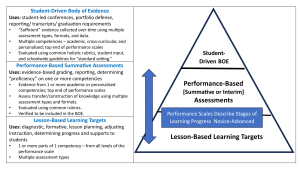

Assessments are used to collect evidence of learning, but not all evidence is created equal. Evidence included in a defensible BOE should be:

- aligned with agreed-upon learning expectations (e.g., academic competency statements, Profile of a Graduate, personalized competencies);

- thorough (sufficient in the amount of assessment data and coverage);

- balanced (using a variety of assessment tools and formats); and

- well organized around broadly stated learning goals (e.g., academic domains, career-based competencies, personalization goals).

Each area of business and industry describes a defensible BOE contextually. This means that within a discipline, such as scientific research or policy making, credible methodologies are defined for collecting and analyzing evidence before coming to a defensible conclusion.

In Deeper Competency-Based Learning, the authors describe a BOE as containing “student work samples – some common and some unique – and possibly additional evidence of learning such as test scores, mentor feedback, and student reflection pieces. Student work samples are placed, and sometimes replaced in an individual student’s BOE, which might be organized using a digital portfolio. Verification guidelines are created as to what types of evidence, what quality of evidence, and what to look for in determining whether there is sufficient evidence of proficient performance. Questions, such as ‘does this represent the student’s best work’ or ‘is it representative of typical and consistent work over time must be answered and clarified. Once a common set of criteria has been defined, teams of educators review BOE evidence to make decisions that will be reported to parents and students” (p. 42).

Below is a description of the evidence that comprises a competency-based BOE.

The Guiding Principles of the IMPACT Framework

According to the dictionary, “impact” refers to the power to bring about a desired result. A set of guiding principles that embody the core values of competency-based education can serve as a North Star for goal setting and decision-making when establishing verification protocols for building a defensible body of evidence. In our forthcoming book, we use the acronym IMPACT to explain these principles.

A defensible body of evidence should Illuminate deep learning, using Multiple sources and student-centered Pedagogies, promoting Assessment practices and Collective actions that are Transparent to all members of the learning community.

Illumination: The collection and analysis of each student’s work products should shed light on the depth, breadth, and complexity of understanding when students apply and extend knowledge. A defensible body of evidence begins with rigorous, agreed upon learning expectations requiring students to transfer what they’ve learned to new, authentic contexts.

Multiple sources: Proficiency-based decisions, grading, and reporting draw upon a “sufficient” amount of evidence from multiple sources, collected over time, demonstrating learning processes, progress, and products.

Pedagogy: Educators study instructional approaches to determine how effectively they reflect a school’s vision and support learners in reaching their full potential. Evidence of learning is based on pedagogies that support student-centered learning and encourage student ownership, agency, and voice.

Assessment: The Latin origin of the word “assess” (assidere) meant to “sit beside” a learner. Evidence collection is guided by collaborative decision-making about how best to “meet every student where they are” using varied assessment forms and formats, including performance-based (e.g., product development, investigations) and metacognitive assessments (e.g., reflective essays, peer- and self-assessments).

Collective actions: According to John Hattie, collective teacher efficacy is the belief that through collective actions, educators can influence student outcomes and increase achievement. Donohoo further emphasizes that collaborative conversations should be based on evidence of learning. Judgments in a competency-based system are made based on collaborative decisions and agreed upon rules, protocols, and practices for making and acting upon those decisions.

Transparency: Learning expectations and decisions for making judgments are transparent to students, teachers, and the broader learning community.

Beginning With a Common Vision

Schools shifting to a competency-based (also referred to as proficiency-based) learning system typically began by developing a collaborative vision that embodies the transformation they envision. For example, many schools develop a Profile of the Graduate (also referred to as Profile of the Learner, Proficiency-Based Graduation, etc.). Other schools frame common personal and academic expectations for students in other ways. For example, Gainor (2023), describes a framework for schools around the world that have adopted an approach called Challenge Based Learning because of its ability to empower students and teachers to be co-learners. This framework defines three broad learning goals for every student: Engage through essential questioning; Investigate real-world challenges; and Act by developing and sharing evidence-based solutions with an authentic audience. This vision has transformed how and why learning happens in each of these schools, with students applying 21st century skills in a variety of ways.

Establishing verification guidelines for how to build a “defensible” BOE influences decisions made about the instructional pedagogies we use, how we design assessments, and how we approach evidence-based grading.

In part 2, I make connections between the seven design principles of competency-based learning systems and a defensible BOE.

Learn More

- CBE Starter Pack 2: Meaningful Assessment

- 4 Keys to Building Deeper Critical and Creative Thinking in Your Classroom

- Showcase, Share, Inspire: Performance-Based Assessment and Competency-Based Learning in Chicago Public Schools

- How Standards-Based Grading Led Us to Empower, Part 2: The Power of Evidence

- The Shift In Action: Five Takeaways From Our Journey Towards A Competency-Based System

Karin Hess, author of numerous books and the Hess Cognitive Rigor Matrices, is a former classroom teacher and school administrator now providing support to CBE schools. Visit Karin’s website at www.karin-hess.com.

Karin Hess, author of numerous books and the Hess Cognitive Rigor Matrices, is a former classroom teacher and school administrator now providing support to CBE schools. Visit Karin’s website at www.karin-hess.com.