But What About The Test?

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post originally appeared at the Mastery Collaborative on June 11, 2019.

How can high-stakes testing “live” in a setting that also uses mastery-based grading? Project-based learning? Culturally responsive practices and content? Too often, innovative school design is thought of as difficult or impossible to implement amidst heavy testing requirements. But success on standardized exams is not incompatible with mastery-based grading and project-based learning. In fact, I have seen in my fifteen years in education how these two innovative approaches facilitate a wide range of success at schools.

I often hear from and read about practitioners who worry about tests, especially high-stakes tests. It is not their fault. As practitioners, we receive mixed messages with one message usually the loudest: the test is the most important, the test is the data, the test defines your teaching, the test, the test, the test.

There is a lot of valuable research and data that underscores the lack of authenticity and inequity inherent in high-stakes standardized testing. But, I hope to provide a perspective of an educator doing innovation work “on the ground” while addressing the reality of standardized tests. To be clear, this piece is not advocating for standardized tests, rather it’s a demonstration that high-stakes testing does not erase the feasibility of innovative practices like mastery-based learning.

While we wait for large-scale change in states where high-stakes testing is prevalent, replicable innovations are happening in small pockets across the country. It is possible to destigmatize “teaching to the test” when it becomes teaching skills that are prevalent on the test.

I am a teacher and instructional coach at The Young Women’s Leadership School of Astoria (TYWLS), a grade 6-12 public school in the New York City Department of Education. Our school is just one example of a “testing” school that also uses innovative practices, including a whole-school, mastery-based grading system. Our students find success on the multiple New York State exams and AP exams they take each year. We have been able to find a successful balance between the tension of innovation and standardized testing.

As a Living Lab site for the NYC DOE’s Mastery Collaborative, we often host visitors and present at conferences about our whole-school mastery-based grading system. At every session, there are folks who quickly reveal a seemingly fixed mindset about the importance of “the test” as well as the challenges testing presents. We try to make the connection for practitioners in traditional settings that they likely do this type of work already by analyzing what’s on the test and teaching and reteaching skills and content. What is different about planning mastery-based curriculum using a project-based methodology that includes a high-stakes test is that we prepare for, but go well beyond, the test.

Know Thy Test

All data can be useful if you know how to use it. Even the data we receive from exams. But far more informative is our day-to-day systematized and transparent data about student’s mastery of skills. At the base of our curriculum planning, we have a mastery grading system designed. Our learning targets and rubric criteria are written and aligned with 21st-century skills and content standards alike.

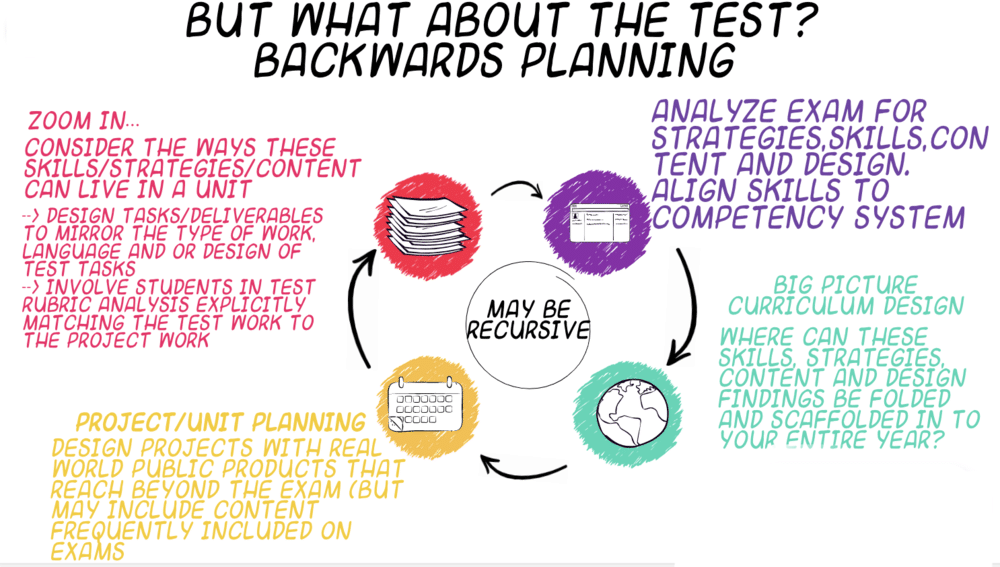

To plan a curriculum that acknowledges and prepares students for a high-stakes test, we begin by deeply analyzing and dissecting the exam, noticing trends over time in regards to the skills students will need to master to be successful. We highlight repeating skills, themes, vocabulary and even the structural design of the exam and align them to our already-created mastery system, which is robust enough to include anything that comes up in our dissection. If there is a high-frequency skill that is not addressed by our grading system—a rare occurrence—we will discuss this skill as a department to determine if additions or adjustments need to be made by adding a larger 21st-century skill to our system.

During dissection, we collect content or content-based themes that repeat over the test and across years. We thoughtfully fold these themes and content into our projects. But those less-frequent or one-off aspects of content can be memorized right before the test.

But, What Does it Look Like?

At TYWLS of Astoria, our grading system, rubrics, findings from the test, and project-based learning design principles guide and shape our big-picture planning work. We design projects or units that are authentic and rooted in real-world skills, and that also allow for a recursive folding in of the high-frequency test-dissection findings. This is a puzzle, and it is not easy work, but it is worth-it work.

As we move into more detailed curriculum design, aspects of the exam are woven into each project or unit. Looking across the year at projects in, say, a U.S. History course, the repetition of primary source document analysis comes across clearly. It is a skill needed for the test, but we fold it into a project, such as a recent “Truth to Power” project. Students were challenged to write letters to policymakers sharing their ideas about how to end mass incarceration and eliminate racial caste systems. Throughout this project, assessments and experiences are designed with the U.S. History Regents skills practiced throughout. [Regents are the New York state high school exams.] Because the project is completely planned and student-centered, the teachers are freed up during project time to coach students. They have designed formative assessments, including Regents-style document dissection, that allow them to individually coach or work with small groups to support student mastery of skills.

As we move into more detailed curriculum design, aspects of the exam are woven into each project or unit. Looking across the year at projects in, say, a U.S. History course, the repetition of primary source document analysis comes across clearly. It is a skill needed for the test, but we fold it into a project, such as a recent “Truth to Power” project. Students were challenged to write letters to policymakers sharing their ideas about how to end mass incarceration and eliminate racial caste systems. Throughout this project, assessments and experiences are designed with the U.S. History Regents skills practiced throughout. [Regents are the New York state high school exams.] Because the project is completely planned and student-centered, the teachers are freed up during project time to coach students. They have designed formative assessments, including Regents-style document dissection, that allow them to individually coach or work with small groups to support student mastery of skills.

Another project, in 11th grade English, is called “Exploding the Canon,” in which students propose curriculum design to high school teachers and professors of teacher education. They provide evidence for their selections, which often work to diversify the texts read in high school English classes. All of the aspects of the NY State English Regents exam, in this case, can be folded into this project. Non-fiction and fiction short and long readings with any high-frequency skills or content are layered in, and essays leading up to the proposal are designed to look and feel like the test essays but contribute to, and often form the basis of, the project.

The designers of these projects have created memorable experiences and provided opportunities for students to collaborate and do deep, meaningful work. Student work becomes the project, and, best of all, they are preparing for the test without the stress of the test while building widely applicable skills. When projects are engaging, students more easily transfer their skills and understanding of content from project to project and then to a testing situation.

Across the country, practitioners, schools, and even districts are designing innovative curriculum that also prepares students for high-stakes testing, and it is a constant, evolving process. Even at our school, with an established mastery-based grading system and a project-based learning approach, practitioners are constantly iterating on their practice in this regard. I hope that other learning environments that have found similar success in navigating the tension between high stakes testing and innovations will share their practices. By designing curriculum in this way, we are both providing the students with power for the exams they need to take now and also sending a message to them that it is not the test, the test, the test.

Learn More

- Shifting the English Department to Competency-Based Assessment

- Keeping Students at the Center with Culturally Relevant Performance Assessments

- What Does it REALLY Mean to Do Standards-Based Grading? (Part 1)

As Springpoint’s Director of Leadership & School Design, Christy Kingham supports the design and implementation of new, student-centered school models. Prior to joining Springpoint, she worked with The Young Women’s’ Leadership School in Astoria, Queens, for eight years as an Instructional Coach and Curriculum Developer in addition to teaching English and working with colleagues to design and implement a nationally acclaimed competency system. Christy was a teacher-leader with the New York City Writing Project and has been an adjunct professor with Drexel University’s Graduate School of Education for the past ten years.