CBE Starter Pack 7: Establish Rigorous, Common Expectations with Meaningful Competencies

CompetencyWorks Blog

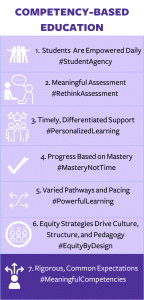

When educators begin to explore competency-based education (CBE), the CompetencyWorks Initiative is a key place to start, but it can be overwhelming to take it all in. This post on meaningful competencies is the final of a series of “CBE Starter Packs” focused on each of the seven elements of the Aurora Institute’s 2019 CBE Definition.

Meaningful competencies, CBE Definition Element 7, guide the purpose of all of our efforts to support learners. This post begins by articulating the role of competencies in a CBE system and the way competencies can connect to a vision for student learning. Next, I outline key design decisions for creating competencies and provide examples that illustrate these decision choices. Like all of the Starter Pack posts, this post suggests indicators for the student experience and system structures and policies. Finally, I close with resources for learning more and getting started.

Meaningful Competencies Form the Foundation in CBE

Meaningful competencies form the foundation – and set the ultimate destination – in a CBE system. In the definition we talk about meaningful competencies to establish rigorous, common expectations. In practice, the language to name competencies varies from place to place. Some examples of other terms include shared learning goals, deeper learning goals, attainments, critical skills, and habits of success. What is important is that the competencies are known to learners.

Competency-based education systems raise the bar in two ways. First, they expand the definition of student success to include the higher-order skills and dispositions needed to transfer and apply knowledge to novel situations. Second, they expect that all students will meet this bar. CBE Definition Elements 1-6 support designing a learning environment that can ensure all students can demonstrate the competencies at an expected high level. Element 7 focuses on how CBE expands the definition of student success.

CBE Quality Principles 10 (Seek Intentionality and Alignment) and 12 (Maximize Transparency) highlight the idea of a “common learning framework” that clarifies what is expected for students to know and do at each performance level or grade level. The common learning framework is transparent to all. Students (and their families) know where they are on their learner continuum, their progress and growth. Teachers build a shared understanding of what student proficiency looks like, align instruction and assessment to the appropriate level of cognitive rigor, and share knowledge of instructional strategies.

The competencies or common learning framework are the structure to which all other aspects of competency-based systems align. That system aims to balance flexibility for students with different strengths, interests, and aspirations to learn along multiple pathways. The system maintains a rigorous commitment to ensuring all pathways and all demonstrations of student mastery reflect the competencies that define success.

Drawing from a Shared Vision of Learner Success

CBE emphasizes a shift to higher-level competencies that include transferable skills and dispositions in addition to academic knowledge and skills. As such, the potential value of beginning from a shared vision is two-fold: 1) competencies demand rigorous, deeper learning instruction and assessment, and 2) competencies can reinforce a sense of purpose and make connections for students about why it is important to reach proficiency on standards.

Developing a profile of the graduate (also known as portrait of a graduate, vision of the graduate, learner profile, etc.) through an inclusive process offers a promising entry point for defining a shared vision of learner success. A shared vision can build understanding and transparency about the purpose and value of CBE.

Through community dialogues about what stakeholders want for their learners, states, districts, or schools can define well-rounded competencies that all students will demonstrate by graduation. The following considerations support creating an effective process to develop a shared vision of what students need to know and be able to do for future success.

- Take proactive steps to include and elevate all voices – particularly those that have been historically marginalized.

- Include what it means to be college and career ready in your definition of success, but don’t limit yourself to academic knowledge. Integrate the skills to transfer and apply that knowledge, and a set of lifelong learning skills that enable students to be independent learners.

- Use the available research on skill sets that link to success in the dimensions of life, college, and career that stakeholders care about.

Expanded definitions of success are particularly important for students who have been historically marginalized and who are likely to encounter discriminatory barriers and other challenges in their lives because of their race, ethnicity, disability or where they were born. Lifelong learning skills and positive cultural identity empower all students to navigate through and around barriers, self-advocate, and effect positive change in their lives and communities.

Translating the Vision into a Competency Framework

Many different approaches to the technical aspects of designing competency frameworks can feel overwhelming. While CBE is not one-size-fits-all and asks communities to own their vision for learners, it is also not necessary to start from scratch on your competency framework. It can also be helpful to work with an experienced technical assistance provider whether you choose to design from the ground up or to adapt existing frameworks to align with your local vision. This section outlines a few key dimensions along which competency frameworks can vary. While there is not necessarily a “right” or “wrong” approach, it’s good to consider the implications of different design decisions.

Starting from the Big Picture Vision or from the Standards

We discussed the value of starting from a shared vision in the prior section. In early stage competency-based schools, another approach has been to start from grade-level state standards and identify “power standards” that spiral from grade to grade or within a discipline. Starting from the big picture may make it easier to get beyond the siloed nature of organizing the curriculum by discipline to a more interdisciplinary and integrated curriculum that is more reflective of the world beyond school. On the other hand, it can feel like a much bigger conceptual shift from grade-level, disciplinary standards.

The relationship between competencies and state standards often comes up throughout the design and implementation process. A helpful analogy can be to think of the state standards as the disciplinary skills and content vehicle by which students develop competencies — i.e., the higher-order thinking skills that transfer across contexts and disciplines. The reDesign post, What IS the difference between competencies and standards?, and the chart in South Carolina’s FAQ 8 can be helpful in thinking about this relationship. In the field, there is a range of practice from using a competency framework as the primary source of learning goals to using a set of competencies side by side with the standards.

Designing an Integrated Competency Framework or Complementary Academic and Adaptive Competency Frameworks

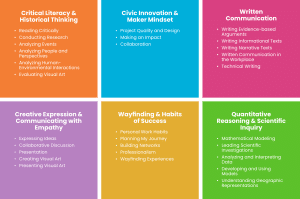

Some systems have one set of competencies that include both academic and dispositional skills. Profile of the South Carolina Graduate (PSCG) Competencies and Building 21 Competency Framework are examples of integrated competency frameworks.

Other systems have a set of competencies focused on social-emotional skills and dispositions that work in tandem with academic competencies or simply the state standards. The Chicago Public Schools CBE pilot cohort takes this approach with a set of adaptive competencies. Schools designed from the Coalition of Essential Schools principles often call these competencies “habits of success.” The Vermont Agency of Education’s Proficiency-Based Graduation Requirements page and the Rhode Island Learning Champions are examples that include academic content areas (e.g., math, English, science) as well as for transferable skills that cross content areas (e.g., effective communication, creative and practical problem-solving).

Other systems have a set of competencies focused on social-emotional skills and dispositions that work in tandem with academic competencies or simply the state standards. The Chicago Public Schools CBE pilot cohort takes this approach with a set of adaptive competencies. Schools designed from the Coalition of Essential Schools principles often call these competencies “habits of success.” The Vermont Agency of Education’s Proficiency-Based Graduation Requirements page and the Rhode Island Learning Champions are examples that include academic content areas (e.g., math, English, science) as well as for transferable skills that cross content areas (e.g., effective communication, creative and practical problem-solving).

A related design element is the extent to which a competency framework focuses on the interdisciplinary and cross-cutting nature of transferable skills or remains organized by discipline. The South Carolina “Reading Critically” competency could be addressed within an English language arts (ELA) curriculum and also in any number of other content areas. The Building 21 competency framework situates the “Read Critically” competency within the ELA Core Content Domain. It is worth noting that reflection and revision is a part of the process, and that Building 21 is exploring new ways to organize its competencies in an increasingly interdisciplinary way.

Determining the Performance Levels

Another design decision involves the performance levels of a competency framework. Many systems start with grade-level expectations and use some version of performance level descriptors that start with “not yet” or “in progress” to “meeting” and “exceeding” proficiency. The VT and RI examples above and the Utah Mastery. Autonomy. Purpose (MAP) Portrait of a Graduate Competencies are organized by grade band groupings, which allows more flexibility than grade by grade.

Another approach uses a “learner continuum” that describes multiple performance levels to indicate student progression based on where they are rather than where they should be based on their age or grade. This continuum or progression approach offers the potential for greater flexibility in when and where students learn and demonstrate each competency. For example, each of the skills within the 12 South Carolina competencies contains six readiness levels. Rather than equating to a specific grade level, each level represents stages of learning spanning from childhood to adulthood. In the Building 21 taxonomy, illustrated below, Levels range from 2-12, with level 10 equating to college and career ready.

What to Look for in the Student Experience

Can you see these student experience “look fors” in the examples above?

- All students, including those who are learning at levels below their age-based grade, have opportunities to apply knowledge and skills.

- Students understand where they are in their personalized pathway and the cycle of learning. When asked, students can tell you what they are working on and how it relates to competencies they will need in their future.

- Definitions of student success include academic knowledge, the skills to transfer and apply that knowledge, and a set of lifelong learning skills that enable students to be independent learners.

- Students and parents understand that there is a difference between age-based grade level and personalized performance level and where students are in developing both academic learning and the broader set of skills and dispositions.

What school policies and practices support meaningful competencies that set rigorous, common expectations?

- Districts and schools articulate learning goals to ensure each and every student is fully prepared for college, career, and life. A graduate profile often captures these outcomes with an emphasis on academic knowledge, transferable skills, and the skills for lifelong learning.

- There is a school-wide strategy for helping students understand graduation-ready competencies and an opportunity to work on cross-cutting, transferable skills in multiple settings so students can see how they differ within different disciplines.

- A transparent learning framework is developed and used to align instruction and assessment to a competency framework.

- Measures of student outcomes are well articulated, including how equity in outcomes is being measured. Calibration processes are in place to ensure consistency in assessment.

- What proficiency looks like at each performance level, accompanied by examples of student work, is available to students and families.

Learn More

There are many resources contributing to our knowledge and practice of meaningful, rigorous competency design. Here we highlight just a few.

The CompetencyWorks report, Habits of Success: Helping Students Develop Essential Skills for Learning, Work, and Life, synthesizes the latest research and knowledge on emerging practices for habits of success including design, examples, and recommendations for supporting students.

The CompetencyWorks report, Habits of Success: Helping Students Develop Essential Skills for Learning, Work, and Life, synthesizes the latest research and knowledge on emerging practices for habits of success including design, examples, and recommendations for supporting students.

- The CompetencyWorks report, The Art and Science of Designing Competencies, provides insights into the orientation and processes that innovators use in designing competencies.

- There are several tools that offer criteria for reviewing the efficacy of competency statements, such as the Great Schools Partnership’s Design Criteria Chart (one of many tools in Proficiency-Based Learning: A Roadmap for Educators) and New Hampshire’s Competency Validation Rubric.

- The blog post, Five Big Ideas for Learner-Centered Competency Framework Design, offers design principles and equity checks, with some background on the development of the South Carolina Profile of the Graduate competencies.

- The CBE Design Principle 7 Rubric is a resource from the book, Unpacking the Competency-Based Classroom, in which Vander Els and Stack offer a roadmap for transforming schools in pursuit of greater equity through competency-based learning. It has indicators for the Framework of Standards, Competencies, and Dispositions; Cognitive Demand; and Systems of Calibration.

- The Essential Skills and Dispositions: Developmental Frameworks resource offers research-based developmental progressions for collaboration, communication, creativity, and self-direction in learning.

- Finally, I can’t resist offering a few more examples from the field:

- Hawaii’s Nā Hopena A‘o (HĀ or BREATH) provides an example of a set of habits grounded in local culture.

- The South Bronx Community Charter competency framework includes 66 “attainments” grouped into 19 competencies that includes both academic and social/emotional skills for college and career readiness.

Supporting Design and Equity Principles for Meaningful Competencies

The information above draws from key Aurora and CompetencyWorks publications. In particular, Designing for Equity: Leveraging Competency-Based Education to Ensure All Students Succeed and Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education.

Key Equity Principles:

- Engage the Community in Shaping New Definitions of Success and Graduation Outcomes (p. 17)

Key Quality Principles:

- #8 Design for the Development of Rigorous Higher-Level Skills (p. 63)

- #10 Seek Intentionality and Alignment (p. 71)

- #12 Maximize Transparency (p. 81)

Get Started

Reading various competency frameworks and applying them to yourself is a great way to explore design options – what is your evidence for your own level of proficiency on a Building Networks or Sustaining Wellness competency?

Reflecting on your own or with your team, school, district, and/or community is a great way to identify current assets to build on in designing meaningful competencies that set rigorous, common expectations.

- What strategies have been effective for engaging the most marginalized parts of the community in developing a shared definition of student success?

- What are the expectations for the skills, knowledge, and traits that students will need for lifelong learning and preparation for college and career? How are these reflected in graduation competencies and other certifications of learning?

- What structures and systems of accountability are in place to ensure that all pathways to graduation are equally rigorous, and that students from historically marginalized communities have the resources they need to attain graduation outcomes at the same rate as their peers?

- In what ways do district and school culture, structures, and pedagogies align to ensure that students build the necessary knowledge, skills, and habits? In what ways do they not align?

Even if your school is not making the move to CBE, it is possible to get started on your own or with a small team. Equitable grading practices and The Modern Classrooms Project are examples of entry points that prompt individual teachers (as well as systems) to define rigorous, transparent learning goals.

Good luck, and if you are looking for additional resources, try browsing past posts on the CompetencyWorks Blog with its many stories of lessons learned by innovators and early adopters from across the field of K-12 competency-based education.

Read the Other Posts in the Starter Pack Series

- CBE Starter Pack 1: Students are Empowered Daily

- CBE Starter Pack 2: Meaningful Assessment

- CBE Starter Pack 3: Timely, Differentiated Support

- CBE Starter Pack 4: Progress Based on Mastery

- CBE Starter Pack 5: Learn Actively With Varied Pathways and Pacing

- CBE Starter Pack 6: Equity Strategies Drive Culture, Structures, and Pedagogy – Aurora Institute

Laurie Gagnon is the Aurora Institute’s CompetencyWorks Program Director.