Competency-Based Education Needs Deeper Evaluation of Educational Equity Outcomes

CompetencyWorks Blog

The Aurora Institute’s definition of competency-based education says that “strategies to ensure equity for all students are embedded in the structure, culture, and pedagogy of schools and education systems.” We draw on two complementary definitions of educational equity. The Great Schools Partnership says, “Educational equity means ensuring just outcomes for each student, raising marginalized voices, and challenging the imbalance of power and privilege.”

The National Equity Project says, “Educational equity means that each child receives what they need to develop to their full academic and social potential. Working towards equity in schools involves:

- Ensuring equally high outcomes for all participants in our educational system;

- Removing the predictability of success or failure that currently correlates with any social or cultural factor;

- Interrupting inequitable practices, examining biases, and creating inclusive multicultural school environments for adults and children; and

- Discovering and cultivating the unique gifts, talents, and interests that every human possesses.”

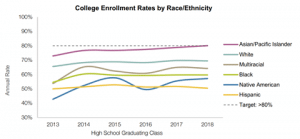

During the Aurora Institute’s recent Strategic Reflection on the Field of Competency-Based Education webinar, I presented two of many possible examples of unequal outcomes by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. The graphic below from the New England Secondary School Consortium shows that Black, Hispanic, Native American, and multi-racial students enroll in college at much lower levels than white and Asian/Pacific Islander students.

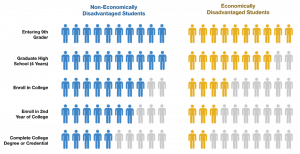

Our education system also produces stark disparities in educational outcomes by socioeconomic status (which is strongly related to race and ethnicity). The graphic below, from the Great Schools Partnership, shows that entering 9th graders from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are much less likely to graduate from high school, half as likely to enroll in college, and less than half as likely to complete a college degree or credential.

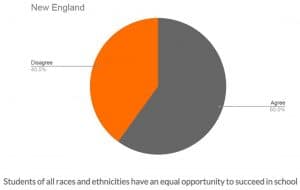

One important reason to share these findings is that many people who espouse an equity orientation report not knowing about existing opportunity gaps. In a 2019 Rennie Center study, more than 90% of survey respondents said they believe it’s important that all students have the same opportunity to succeed, even if that means some students receive more resources than others. However, as shown below, 60% of respondents said that students of all races and ethnicities have an equal opportunity to succeed in school.

These findings were on my mind when I read a recent letter to the editor in EdWeek. The author wrote, “By using disparities of outcome as an unquestionable signal of present racism, critical race theorists are pressuring educators across our country to lower behavioral and academic standards to achieve a shallow version of ‘equity’ that covers up deeper problems.”

Multiple parts of those claims warrant a closer look. First is the suggestion that outcome disparities are not “an unquestionable signal of present racism.” The current education system, with its persistent racial disparities and resulting socioeconomic impacts, exemplifies the definition of institutional racism: it “favors members of the dominant racial or ethnic group…while discriminating against or harming members of other groups, ultimately serving to preserve the social status, economic advantage, or political power of the dominant group.”

Second, the author did not explain why he believes that educators are lowering standards (and that pressure from critical race theorists is the cause). But what also stood out to me was the gap between his claims and competency-based education principles, which seek to eliminate outcome disparities not by lowering standards but through “rigorous, common expectations for learning knowledge, skills, and dispositions” and “timely, differentiated supports based on [students’] individual learning needs.”

To know if these practices are having their intended impacts, the field of competency-based education needs greater transparency about progress toward educational equity. We do have examples of progress, such as California’s Lindsay Unified School District, whose student body is 95 percent Hispanic and 91 percent eligible for federal lunch programs. While implementing a competency-based model, they achieved higher rates of graduation and college enrollment than comparable districts, while strongly improving their performance on state assessments and the state’s School Climate Index.

The recently published, peer-reviewed longitudinal study of 23 Big Picture Learning schools also provides evidence related to educational equity from a network of deeply student-centered public schools. Depending on the school, 62–74 percent of students were eligible for free or reduced price lunch, and “students of color made up 75% of the sample.” The study finds that the graduation rate of Big Picture students six years after college enrollment is “twice as high as the national average for peer demographic groups from the lowest income group”—specifically, 29 percent versus 14 percent. This approaches the national rate of 33 percent for all students, regardless of income. The study also provides self-report data from Big Picture students and teachers on outcomes that are seldom measured but increasingly recognized as important for postsecondary success, such as student resourcefulness, close relationships with supportive adults, and real-world learning during high school. (For full disclosure: my students at a Big Picture School and I were participants in the study, and I have been a Big Picture Learning employee.)

We need to continue building a body of evidence that assesses the effectiveness of high-quality, competency-based education systems in achieving educational equity. Some of the data, such as attendance, graduation rates, and scores on state assessments, may be available through public sources but require additional effort to assemble, analyze, and disseminate. These types of indicators have well-known limitations but in many cases are the only ones accessible for comparing innovative settings to more traditional ones. Other indicators that are central to the goals of competency-based education—including skills and dispositions such as self-direction, collaboration, a growth mindset, and many others, as well as a range of short- and long-term college, career, socioeconomic, and other postsecondary outcomes—are not routinely collected.

As a field that is serious about educational equity, we need to increase our capacity and efforts to assess and evaluate these important outcomes and share them transparently. I emphasize “as a field,” because this is a systems challenge. Many schools and districts have the capacity to conduct some analyses, and some are already doing so. However, external supports or increased budgets for evaluating equity on a range of outcomes will be needed for conducting more widespread, rigorous, transparent, and meaningful research.

Increasing investments in research and development to build the field’s capacity to support this work will enable us to share successes, learn from challenges, and continue building demand for urgent course corrections so long as disparities remain. I welcome conversations with practitioners, policy makers, researchers, and funders who are invested in advancing this agenda, and with schools and districts that have conducted studies or would like to discuss research strategies.

Learn More

- New Educational Equity Resources to Transform Schools and Systems

- Book Review: So You Want to Talk About Race, by Ijeoma Oluo

- The Dangerous Narrative That Lurks Under the ‘Achievement Gap’

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.