Springpoint’s Phased Approach to Implementing Competency-Based Education, Phase Three: School Schedule and Student Learning Progression

CompetencyWorks Blog

This series describes Springpoint’s approach to implementing competency-based education (CBE) with schools, districts, and networks. We developed a resource that outlines the three sequential phases of CBE and guides schools as they embark on this exciting journey.

This series describes Springpoint’s approach to implementing competency-based education (CBE) with schools, districts, and networks. We developed a resource that outlines the three sequential phases of CBE and guides schools as they embark on this exciting journey.

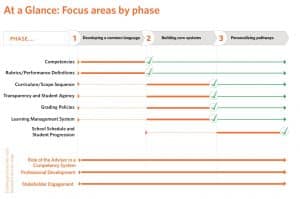

In this third post in the series, focused on phase three, we discuss personalizing pathways to graduation. We encourage partners who’ve progressed to this phase to focus their time on changing or aligning the school’s schedule and crystallizing the student learning progression to enable the kind of personalized pathways that result in differentiation, investment, and true student ownership of learning. You can read the first post to learn more about developing a shared language, selecting competencies, and building out accompanying artifacts. The second post discusses how teams can build core systems to enable CBE implementation. The snapshot below provides an overview of the three phases.

Similar to the first two phases, we have identified a set of questions for this phase that can help practitioners in their CBE implementation work:

- What is the framework upon which the master schedule is built?

- What does it mean for a student to progress within and across courses or learning experiences? Do projects or units of learning occur for a fixed or variable amount of time based on student need and mastery attainment?

- What is the desired balance between individual learning and cohort-based experiences?

- What learning experiences beyond in-school instruction can be awarded credit (both competency-based and traditional course credit)?

- What shifts in resources may be needed to support this personalized model (e.g., budget, roles and responsibilities, school calendar)?

It is at this point in the implementation process that students begin to progress and earn credits on the basis of demonstrating mastery at specified performance levels for each competency instead of seat time. Ultimately, the schedule should be flexible enough to adjust to the needs of students by carefully balancing opportunities for self-paced learning while safeguarding time and space for collaborative learning. This requires a big shift. Schools are now organizing students’ time around specific work products rather than traditional classes.

A more modular and dynamic approach to scheduling helps shape the structure of each students’ day so that time is apportioned based on the performance task and what it requires. Perhaps this means a student spends three days on a project—or maybe it’s three weeks—but whatever it looks like, the schedule is designed in service of helping students attain mastery on key competencies. When mastery becomes the north star, taking precedence over “covering” content standards or the need to pass a particular test, students experience more rigorous and purposeful learning and are set up for success on high-stakes tests and in their college and career pursuits.

The exact nature of the schedule and personalized model will vary significantly based on a school’s model, but schedules that emerge in phase three are often marked by the following:

- Students move on in their learning journey when they are ready.

- Credits are allotted based on mastery, not seat time.

- Students work more frequently based on performance levels instead of age-based grade levels.

- Projects increasingly become cross-disciplinary, providing opportunities for creative use of time.

Ultimately, a competency-based system can enable individualized student progression, where students not only move on when they are ready, but educators make sure students are ready before they move on.

Given the increasing needs around student support, educators often find themselves rethinking or re-establishing their role as an advisor in this phase as well. We have seen schools codify the most essential aspects of the advisor role, including:

- Supporting students as they drive their own learning and take on new, increasingly rigorous projects.

- Helping students design their schedule in a way that allows them to pace their work effectively in service of mastery.

- Acting as a thought partner who supports and pushes students to clarify and crystallize their research questions, topics, and projects.

- Supporting students as they take the reins on self-assessment, measuring their own performance against a commonly held standard.

- Playing a role in supporting student learning outside of the classroom or school building, tailored to each students’ interests, through sourcing internship opportunities, helping students enroll in college classes, or highlighting other enrichment activities to support students in mastering key competencies in ways that ignite or invigorate their personal passions.

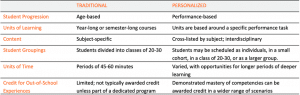

To reach this ultimate phase, it is necessary to move from a traditional school structure to a personalized school structure. While there is no single model for a personalized structure, there are some common characteristics:

Finally, planning for continuous improvement will ensure that a school can live out its promise to leverage CBE as an equitable, rigorous, purposeful approach to helping all students find success. Frequently checking in and adjusting during each phase of implementation is key. But a more systematic approach to continuous improvement will ensure that a CBE system lives beyond the core group of educators who drive initial implementation. Intentionally designed continuous improvement systems include some or all of the following: routine reflection points (e.g., quarterly), data collection and analysis, a mechanism to collect and incorporate student feedback, classroom observations, curricula audits, and review and assessment of student work.

Finally, planning for continuous improvement will ensure that a school can live out its promise to leverage CBE as an equitable, rigorous, purposeful approach to helping all students find success. Frequently checking in and adjusting during each phase of implementation is key. But a more systematic approach to continuous improvement will ensure that a CBE system lives beyond the core group of educators who drive initial implementation. Intentionally designed continuous improvement systems include some or all of the following: routine reflection points (e.g., quarterly), data collection and analysis, a mechanism to collect and incorporate student feedback, classroom observations, curricula audits, and review and assessment of student work.

In addition to these standardized practices, school teams should plan to react to specific developments, such as leadership changes, staff turnover, funding changes, district priority changes, shifts in student needs, and testing or other state-level changes. It is important to assess, address, and adapt based on the realities in a particular community. This will ensure continued alignment as new staff and students enter the school so that no key elements of the system are unintentionally abandoned. Here are a few key questions that can guide a strategic, routine continuous improvement process:

- Are the school’s competencies grounded in current research as those most likely to prepare students for a diverse range of postsecondary opportunities?

- Does the school community still have a strong shared CBE language that is clearly memorialized and utilized across rubrics, student work samples, and student-led conferencing?

- How are competencies embedded into student learning experiences through the curriculum/scope and sequence?

- How do competencies contribute to transparency and student agency in a way that increases a student’s ability to self-assess and direct their own learning?

- How does the CBE system contribute to equity and how is the system examined for ongoing adherence to equity? For example, does the school know if the system is working for everyone? Do they know who is and is not accessing the LMS and progressing in their learning?

- Are your school’s grading policies clear, equitable, and aligned to established standards for postsecondary readiness? Do any biases exist in the way that teachers grade student work?

- Is the learning management system widely used and understood? Does it still achieve the same goals that it was chosen to achieve?

- Do the school’s schedule and student learning progression help students authentically own their learning? Do advisors provide enough support to ensure ALL students are finding success?

Competency-based education holds the promise of helping schools improve teaching and learning, realize an individualized student progression of learning, and instill student agency and investment through transparent learning goals that lead to self-directed learning. In turn, this creates a more equitable learning environment that supports all students to succeed. We hope that breaking CBE implementation into three discrete phases can serve to help schools on the long but important journey to implement a strong CBE model.

Implementing a full competency-based education system is both incredibly complex and extraordinarily rewarding. It not only takes strong leadership, patience, and a clarity of vision, but also a united and supportive community that is committed to building a student-centered culture and doing school differently. The results, however, are transformative for students: improved teaching, more meaningful learning, transparency and increased student agency, more equitable grading practices, personalized pathways, and an environment where systematized practices support all students to succeed. This phased approach to implementing CBE is intended to clarify and break down what often feels like a huge undertaking. We hope that it helps support schools already on the CBE journey and inspires more schools to take the leap.

Learn More:

- Springpoint’s Phased Approach to Implementing Competency-Based Education, Phase One: Establishing a Solid Foundation

- Springpoint’s Phased Approach to Implementing Competency-Based Education, Phase Two: Scaling Key Practices and Building Core Systems

- Scheduling for Personalized Competency-Based Education: Book Review and Reflections on Equity

Elina Alayeva is Springpoint’s Executive Director. As a founding leader of Springpoint, she has grown the organization and its offerings to expand reach and impact. Elina has deep expertise in strategic planning and systems-level alignment to enable successful school efforts, technology-enabled innovation, student-centered school models, and organizational operations. Prior to joining Springpoint, she designed and implemented a year-long funding focus on innovative secondary school models as a program officer with Next Generation Learning Challenges. Previously, she worked at Carnegie Corporation of New York as part of its Urban Education program, focusing on new designs for schools and systems. As a Fulbright Fellow, Elina researched ethno-mathematics in community-run schools on First Nations reserves in Canada. Elina currently serves on the advisory board of CompetencyWorks. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Engineering from The Cooper Union and a Master of Arts in Political Science from Columbia University.

Elina Alayeva is Springpoint’s Executive Director. As a founding leader of Springpoint, she has grown the organization and its offerings to expand reach and impact. Elina has deep expertise in strategic planning and systems-level alignment to enable successful school efforts, technology-enabled innovation, student-centered school models, and organizational operations. Prior to joining Springpoint, she designed and implemented a year-long funding focus on innovative secondary school models as a program officer with Next Generation Learning Challenges. Previously, she worked at Carnegie Corporation of New York as part of its Urban Education program, focusing on new designs for schools and systems. As a Fulbright Fellow, Elina researched ethno-mathematics in community-run schools on First Nations reserves in Canada. Elina currently serves on the advisory board of CompetencyWorks. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Engineering from The Cooper Union and a Master of Arts in Political Science from Columbia University.

Christy Kingham is Springpoint’s Director of Leadership and School Design. She works closely with Springpoint’s partners to support the design and implementation of new, student-centered school models. Christy worked with The Young Women’s Leadership School in New York City for eight years as an instructional coach, curriculum developer, and English teacher. She collaborated with colleagues to create robust student supports, design and implement a nationally acclaimed competency system, and implement intensive passion projects. Christy also taught English for seven years at Fox Lane Middle School in Bedford, New York. She graduated from Georgetown University with a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, Columbia University Teachers’ College with a Master of Arts in the Teaching of English, and Hunter College with a Masters in Educational Leadership. She has also been a teacher-leader with the New York City Writing Project and an adjunct professor with Drexel University’s Graduate School of Education.

Christy Kingham is Springpoint’s Director of Leadership and School Design. She works closely with Springpoint’s partners to support the design and implementation of new, student-centered school models. Christy worked with The Young Women’s Leadership School in New York City for eight years as an instructional coach, curriculum developer, and English teacher. She collaborated with colleagues to create robust student supports, design and implement a nationally acclaimed competency system, and implement intensive passion projects. Christy also taught English for seven years at Fox Lane Middle School in Bedford, New York. She graduated from Georgetown University with a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, Columbia University Teachers’ College with a Master of Arts in the Teaching of English, and Hunter College with a Masters in Educational Leadership. She has also been a teacher-leader with the New York City Writing Project and an adjunct professor with Drexel University’s Graduate School of Education.