Elevating Student Experience to Build Equitable Learning Environments, Engagement, and Agency

CompetencyWorks Blog

Promoting equity and student agency—key elements of competency-based education—requires a deliberate focus on improving students’ experience of their learning environments. That was the message of a recent Aurora Institute webinar. The presenters offered strategies and online resources for increasing student engagement and outcomes by improving their learning environments.

Promoting equity and student agency—key elements of competency-based education—requires a deliberate focus on improving students’ experience of their learning environments. That was the message of a recent Aurora Institute webinar. The presenters offered strategies and online resources for increasing student engagement and outcomes by improving their learning environments.

The approach is based on evidence that students are more likely to engage when they feel valued, have strong relationships with their teachers, and see the relevance of the work they’re doing. It’s also based on evidence that students from traditionally underserved groups experience school more negatively than other students.

The webinar was presented by Dave Paunesku, Executive Director of the Project for Education Research that Scales (PERTS) at Stanford University; Erica Bauer, Director of Community Relations for the Chicago Bulls (formerly of Walter Payton College Preparatory High School in Chicago); Alex Fralin, CEO/Founder of Leading Partnerships; and Nia Innis, a student at Walter Payton College Preparatory High School.

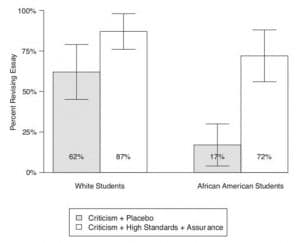

Paunesku began by sharing a rigorous study of teachers’ written feedback on student essays about how they could improve their writing. After teachers wrote their usual feedback, researchers randomly assigned students to receive one of two post-it notes affixed to the front of their essay. The first post-it note was a neutral placebo that said, “I’m giving you these comments so you have feedback on your essay.” The second said, “I’m giving you these comments because I have high standards and I know that you can meet them.” This second post-it note made the teacher’s positive intent explicit. Teachers didn’t know which post-it note each student had received.

Feedback Across the Racial Divide.

Both white and African-American students who received the encouraging message were much more likely to revise their essays. For white students, the impact was substantial—they were 40% more likely to revise than students who received the neutral message. But for African-American students the impact was spectacular—they were four times as likely to revise their essays if they received the encouraging message (see image below). Students who received the more supportive feedback also earned higher grades for the entire semester.

Clearly, some types of teacher comments have a more positive effect than others. The study helps us see that teachers’ intent in providing feedback is often unclear to students. Some students saw teacher feedback as mean-spirited or signaling the students’ lack of potential. The differences between white and African-American students highlight the different experiences that students bring to the classroom and the importance of these types of understandings when striving to create equitable learning environments. (Although it wasn’t addressed in the webinar, I suspect that whether the teacher and student are the same race/ethnicity would also affect the outcomes.)

The findings point out that students don’t always recognize teachers’ positive intent. More generally, the webinar presenters highlighted the importance of actually finding out what students are experiencing across a range of learning activities. Programs that increased students’ sense of cultural affirmation, for example, improved outcomes such as attendance, GPA, and graduation rates.

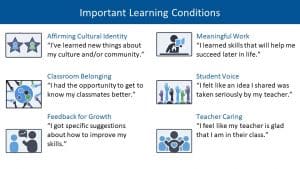

In short, teachers need to understand why students engage in order to be able to support that engagement. “It’s important for educators to have concrete examples of what kinds of experiences their students should be having, as well as simple ways to measure and improve these experiences,” Paunesku said. PERTS has identified six “Important Learning Conditions” for building equitable learning environments that every student should experience: affirming cultural identity, meaningful work, classroom belonging, student voice, feedback for growth, and teacher caring.

They have concluded from research that these six learning conditions help students engage and succeed, and that different subgroups of students experience the learning conditions differently. The post-it note experiment makes it clear that teachers can’t assume what students are experiencing; they have to ask.

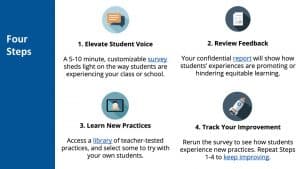

PERTS has developed questions teachers can ask for this purpose and a four-step process for improvement over time that’s summarized in the image below. First, they provide a brief, customizable student survey to understand the extent to which students are experiencing each of the Important Learning Conditions. For example, one question for Affirming Cultural Identity is “In this class, I’ve learned new things about my culture and/or community.” One question for Classroom Belonging is “I feel like my teacher accepts me for who I am as a person.” The survey document also has links to recommendations for now to nurture each learning condition.

After receiving an anonymized summary of student responses, the teacher is encouraged to discuss the feedback with students. This helps students feel heard and become partners in developing an effective learning environment, which is one way the process promotes student agency. Teachers can then access a library of practices to improve students’ learning experiences in relation to the six learning conditions, such as “How to give actionable critical feedback along with reassurance.” Finally, teachers can repeat the process periodically, re-administering the survey to understand the impact of changes in their classroom practice. The tools described here are all available free of charge.

Presenters Fralin, Bauer, and Innis shared additional strategies related to their work with PERTS, the Midwest Network of the National Equity Project, and Walter Payton College Preparatory High School. Through this work they focused on equity, not equality. They identified ways that students of color were doing less well and being underserved compared to white students, and they decided to focus their work on student identities and feelings, including an emphasis on ensuring that Black students’ identifies and feelings were reflected in the classroom.

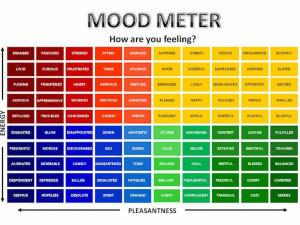

One strategy they used for improving student experience was the Mood Meter, which helps students think about and share how they’re feeling at a particular moment and how this changes over time (see image below). Once students have placed themselves along the two dimensions of Energy and Pleasantness, they can select from a wide range of adjectives that help them identify their emotional state. Bauer noted that some students made fun of the mood meter but over time began referring to it naturally. Their expanding self-awareness and emotional vocabulary contributed to classroom activities designed to improve how students experienced their learning.

Student Nia Innis talked about the importance of feeling that her teachers are caring, understanding, and genuine. Activities with the Mood Meter helped her feel that way. Feeling that teachers cared about her also made Nia feel more comfortable asking for resources and assistance in class, which she said improved her grades and exam scores. She said activities like these should continue throughout the year, not just during culture-building work in the first couple weeks of school.

Finally, Bauer urged educators to focus on promoting student agency and helping students become the center of decision-making processes. Educators who are striving to improve their students’ experiences should do so with their students, not for their students, she said. This requires “shifting the power” to students. The Walter Payton School did this through activities that support student voice, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, story circles, and surveys.

For example, in an interview with a student about why he was struggling to perform well in class, power was shifted by creating ground rules that initially only the student could talk but other adults in the room couldn’t. In a focus group with some students about why they weren’t taking AP History courses, teachers provided a video camera and then left the room, asking students to make a video explaining why. One insight from the video was that students felt the AP History content didn’t reflect their identity, with comments such as “I want to learn about when I was a king or queen before I learn about when I was a slave.” The students reported feeling valued and empowered, knowing that the adults wanted their input in order to improve education and students’ experience in the school.

Free resources for building equitable learning environments to advance equity, agency, and engagement are available at http://perts.net/elevate and https://equitablelearning.org/. Fralin encouraged teachers and students to use the activities in the webinar to co-construct the type of classroom they want to have, saying “that type of power sharing is a game-changer.”

Learn More

- Elevating Student Experience to Build Equitable Learning Environments and Outcomes (webinar)

- Improving School Equity Through A Student-Led PD Activity and an Equity Summit at Casco Bay

- What Do You Mean When You Say “Student Agency”?

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.