Keeping Students at the Center with Culturally Relevant Performance Assessments

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post originally appeared at Next Generation Learning Challenges on June 4, 2019.

Performance assessments provide a critical space for students to reflect on and share their personal stories and their identities as learners.

Performance assessments provide a critical space for students to reflect on and share their personal stories and their identities as learners.

“All instruction is culturally responsive. The question is: To which culture is it currently oriented?”

—Gloria Ladson-Billings

At the heart of the shift toward more student-centered models of learning and assessment is an understanding that learning is socially embedded and that the broader communities that students exist within matter to their learning. Emerging findings from brain science reveal that students’ cultural contexts, in particular, are fundamental to their learning. These findings are not new. They are built upon a rich history of research highlighting how central culturally responsive pedagogy is to providing all students with a high-quality education.

One powerful means of bringing students’ culture into the classroom is through culturally relevant performance assessments. Performance assessments center students’ identity and experiences by asking them to show what they know and can do through multidisciplinary projects, presentations of their learning in front of a panel, and reflections on their educational trajectory. At their core, such assessments provide a critical space for students to reflect on and share their personal stories and their identities as learners.

Lessons From Hawai’i: Defining “Cultural Relevance”

Representatives from the Hawai’i education department and the Hawaiian-focused Charter School (HFCS) network recently shared the ways their state policy and the work of the HFCS school network work together to support culturally relevant assessments that center Native Hawaiian culture in schools across Hawai’i. During a fall 2018 convening in which leaders from HFCS came together with practitioners from districts across California to share lessons from their respective performance-assessment systems, one of the biggest questions that emerged was: What would it look like to employ culturally relevant performance assessments in diverse contexts in which there are many cultures with which students identify?

Charlene Hoe—founder of the Hakipu’u Learning Center in Hawai’i—responded that “culture” is defined by a student’s local context or history: It may include students’ personal racial or ethnic background but it is also defined by their neighborhood, their school, and their home. Making an assessment “culturally relevant” in diverse contexts means allowing students to draw connections between their learning and their direct, daily experiences with the world, and treating those experiences as an asset in the classroom.

Cultural Relevance in Diverse School Systems: Lessons From California

Given this understanding of cultural relevance, it is possible to understand how to design and implement culturally relevant performance assessments to serve diverse student populations. One such context is the California Performance Assessments Collaborative (CPAC), a Learning Policy Institute initiative. CPAC represents policymakers, researchers, and a professional learning community of districts, networks, and schools across the state of California working to study and advance the use of performance assessments. CPAC was founded to help build systems of assessment that more equitably serve all students within diverse student populations; this concern for equity has been a central organizing tenet of CPAC since its inception.

The work of CPAC is being led by school districts such as Los Angeles Unified, Oakland Unified, and Pasadena Unified, which are using performance assessments to operationalize their respective district profiles of college-, career-, and community-ready graduates. These district visions call for students to move beyond the mastery of academic-content knowledge to reflect on their learning, cultivate social-emotional skills, and become civically engaged within their communities.

Although “cultural relevance” manifests differently across CPAC schools based upon their local contexts, the work being led by CPAC members has yielded key lessons about how to make performance assessments culturally responsive in diverse contexts:

STEP 1: Put relationships at the center and provide the space for students to share their stories.

“[The senior defense] gives us a chance to really get to know our kids. … It’s their chance and their moment to shine because they may not have had a moment like that before.”

—School Administrator in Pasadena Unified School District

The public nature of student defense presentations provides a powerful platform for students to share their stories and build stronger relationships with their teachers. Pasadena Unified school district, for example, is in its first year of requiring that graduating high school students complete a senior defense. Students compile a portfolio of “artifacts”—a collection of exemplary samples of their coursework from across their high school years, including an intensive research project—and then reflect on their learning, growth, and future plans in front of a panel composed of their teachers, counselors, family, and other members of their community.

These defense presentations can be a powerful platform for students to reflect on their learning and situate their stories within the context of broader community issues. Research from neuroscientist Mary Helen Immordino-Yang confirms that reflecting on the “broader meaning of tasks helps youth engage deeply with academic content, overcome negative stereotypes, and build purpose.” Because the senior defense encourages students to draw from their own lived experiences, students often use such assessments to explore topics they find personally significant and culturally relevant.

For example, one Pasadena student began her presentation by sharing that she had been raised by a single mother in Peru until age 5, completed pre-kindergarten in Dallas, and moved to Pasadena in 5th grade—which is where she believes her life truly “started.” It was there that she met two teachers who helped her feel at home. “Yes, they are teachers to me,” she shared, “but they are my mentors. They are my father figures. They’ve seen me laugh. They’ve seen me cry.”

Her portfolio artifacts included a research paper investigating affordable-housing policy in Los Angeles, a reflection on her volunteer work, and an original piece of choreography she created with her classmates. As she presented each artifact, she identified how she met graduation outcomes—through research, collaboration, and creativity—and then reflected on what each assignment taught her about herself.

Given her poise, the student’s panelists were shocked when she shared that she had not always been self-confident: “I used to be shy—the girl in the back. I feel like keeping my voice shut and not getting it out there made me belittle myself. I had to learn how to put my voice out there. I want to study psychology and want to help people with suicide problems. If I don’t have communication skills, how am I going to help them?”

Having a safe space in which to share their stories and seeing their stories as part of the acquisition of academic knowledge can empower students to bring their whole selves into the classroom. Cultivating structures for effective caring—spaces in which students and adults can build meaningful one-on-one relationships—can be an uphill battle, especially in large, comprehensive high schools. Performance assessments can help create such spaces because they provide a forum for students to reflect on and share their own stories.

STEP 2: Use students’ personal experiences to drive civic and community engagement.

“My family, as an immigrant family, has struggled receiving and having access to health care. Also, lots of people in my community have that same issue. It was a topic I wanted to bring awareness to because it has limited cultural sensitivity. A lot of people don’t know there’s this issue in the community, specifically this community.”

—12th Grade Student in Oakland Unified School District

In Oakland Unified (OUSD), a growing number of students are completing a graduate capstone project—a performance-based assessment that requires them to spend a year conducting intensive research on a topic they are passionate about and then give an oral presentation about it at the end of their senior year to an audience of their teachers and the broader community. Similar to a senior defense, the graduate capstone project encourages students to use their own identities and interests to guide their research. Said one Oakland student: “You get to show your personality. You go up and present, and they’re like, ‘OK, who is she?’ Your topic kind of gives a little bit of who you are, the way you show yourself, and how you talk. That gets to show the personality and who you are. I think that’s a really cool way to evaluate kids.”

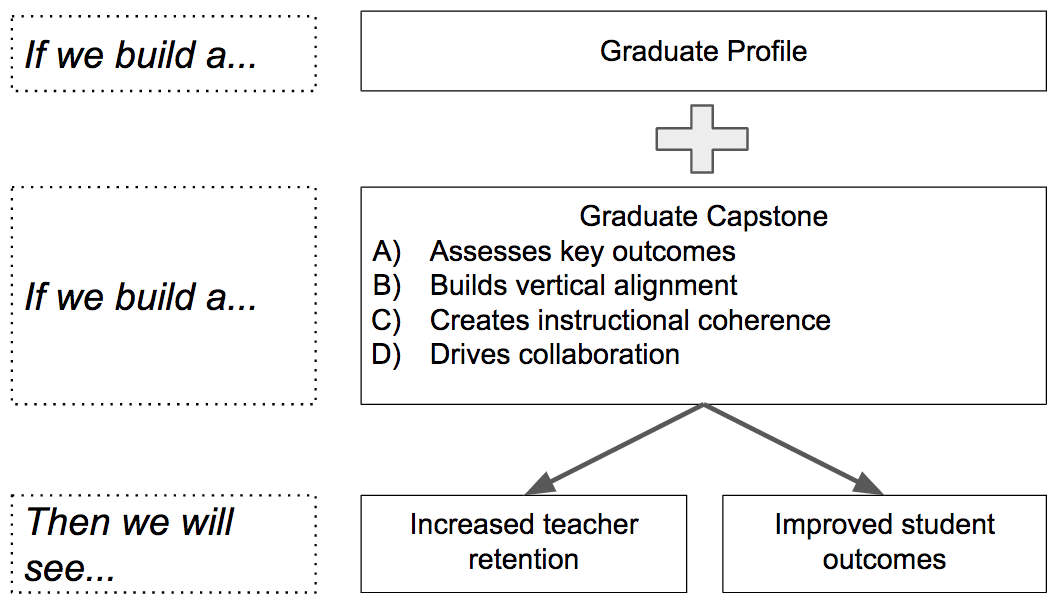

A key requirement of Oakland’s capstone project is that students’ research addresses a local community need. The theory of change for OUSD’s graduate capstone is: If the capstone is built to complement the district’s graduate profile, and K-12 grade-level instruction is vertically aligned with the capstone, then the resulting instructional coherence will promote a positive culture of teacher and staff collaboration and improve both teacher retention and student outcomes.

This way, a student’s capstone research can move from storytelling to civic action. For example, one student in the district used her graduate capstone project to explore systemic and personal solutions to the pervasiveness of flavored-tobacco products in her community. She identified marketing of “kid-friendly flavors” of nicotine that targeted people her age as a key cause of the problem.

As an English-learner, the student entered her senior year thinking that completing the intensive research and presentation that the capstone demands would be “impossible.” However, after interning with a local tobacco-control program and conducting intensive research on the politics of flavored tobacco, she emerged a confident advocate for her community. Compelled to take action on her research findings, the student surveyed 75 students in her school about their tobacco use and presented her findings to 9th-grade students at her school to warn her younger peers of the health effects of nicotine and of the nicotine industry’s dangerous marketing strategies.

By asking students to focus on their experiences in their local communities and to think critically about how to take action in those spaces, performance assessments not only assess students’ skills but are a powerful form of learning and reflection in and of themselves. Encouraging students to address a need in their own community sends the signal that their local communities matter and that they have the power to create positive change within and beyond them.

The Power of Culturally Relevant Performance Assessments

By centering students’ cultures in the classroom, schools are rejecting a deficit view of culture, instead recognizing and celebrating students’ personal experiences as valid and powerful sources of knowledge. This can foster a sense of cultural belonging among all students, especially those whose cultural identities are not traditionally honored and represented in the classroom. The science of learning and development supports this “whole child” approach to education that encompasses social, emotional, and academic learning. By making students’ experiences the focus of their learning, performance assessments serve as an important and effective vehicle for recognizing and exploring students’ rich and varied cultural identities.

Learn More:

- How Competency-Based Learning Supports Culturally Responsive Curriculum

- Cultural Responsiveness Starts in the Principal’s Office

- Why Aren’t We Talking about Culturally Responsive Education in Next Gen Learning?

- How Can I Tell if a School is Using Performance Assessments?

Maya Kaul is a research and policy assistant at the Learning Policy Institute.

Maya Kaul is a research and policy assistant at the Learning Policy Institute.