Let Educators Drive: Gradual Release to Learner-Centered Design

CompetencyWorks Blog

Image: Allison Shelley

This is the third in a series of blog posts focused on how The Center in Iowa is providing web-based tools and resources to personalize professional learning for educators moving into competency-based systems. This blog post focuses on how teachers can be supported to develop autonomy and leadership over their own professional learning and apply it to specific problems of practice in their learning environments.

In the Part 1 of this series, I described The Center’s approach to helping districts find and follow a clear path to personalized, competency-based learning. Part 2 focused on what adult learning looks like when school leaders personalize complex change using educators’ target zones of development and shared problems of practice.

How do we prepare adult learners for competency-based learning experiences?

As mentioned in Part 2 of this series, modeling new professional learning processes is a key step in moving toward educator-driven cycles of learning. Leaders model creating a learning intention grounded in the Aurora Institute’s CBE principles. They also explain how the web-based platform’s embedded resources connect to the larger vision, why they are sequenced the way they are in the action plan, and which specific skills and subskills will be developed and practiced with learners in which order. Through these steps, leaders are able to build collective efficacy around the process before sending educators off to design on their own. This gradual release of responsibility process dissipates confusion, eases anxiety, and provides opportunity to build consensus around the value of educator-driven professional learning.

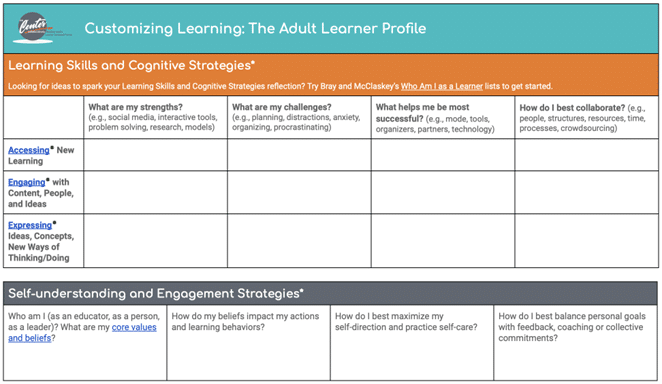

It is also important to facilitate deeper understanding of what makes us more (or sometimes less) successful as adult learners. Just like the young learners in our classrooms, adult learners benefit when they build learner profiles (see Figure 1). At The Center, we use an approach grounded in universal design for learning (UDL), which we derived from the CAST UDL Guidelines and Bray and McClaskey’s work in How to Personalize Learning (2016). The learner profiles engage adult learners in a discovery process about their strengths, challenges, and preferences. This enables them to work with greater power and intention in three areas, as shown in the figure: (1) accessing new learning; (2) engaging with content, people, and ideas; and (3) expressing what they have learned through new ways of engaging learners in their contexts.

Figure 1

For example, the learner profile process may help an educator realize that having a high-level, visual overview enables them to learn something new most effectively. Then, when they are designing a pathway for a learning cycle, the first resource they select from our web-based tools will be a video, an infographic, or a graphic organizer. Or if they have identified procrastination as a challenge, they can work with their teacher team to design productivity practices into their learning cycle. These might include chunking due dates—such as for exploring resources or trying something new with learners—into smaller pieces on a shared digital calendar so they are more frequently held accountable for progress.

These types of facilitated supports set the stage for adult learners to feel empowered by educator-driven professional learning rather than overwhelmed by it. The supports help adult learners develop their learner identity and agency. One way we have found success is to have teacher leaders engage in this process ahead of their peers and then share in whole-staff sessions or in small groups using the following protocol:

- What roses did they discover? (what went well),

- What thorns did they encounter? (what presented a challenge or needed to be worked through), and

- What buds do they see? (ideas they have to improve their design process in the future).

How are educators empowered to customize professional learning to their needs?

Once educators have further developed their identities as learners, the next step is to engage in iterative, job-embedded learning and doing. Staying with the UDL framework, we use a model that moves adult learners through two to four learning cycles per year with the following steps: Access → Engage → Express → Iterate → Reflect → Evolve.

During the Access phase, the schools and districts we support are finding the most success if they have first developed consensus around this process (see Parts 1 and 2 of this series) and are driving action steps through a common set of goals in their building. This focuses time and energy while narrowing the number of principles and practices that will apply during any given professional learning cycle.

The other key is that each teacher or teacher team needs to have set a learning intention before they start. They need to know what problem of practice they are solving in their classroom before they dive in to select a practice to change and improve. Here is a consultancy protocol that could be used to flesh out problems of practice by leveraging personal reflection with collaborative feedback. Another option is to use this systemic process, which can be modified for educator teams to identify a problem of practice for a professional learning cycle.

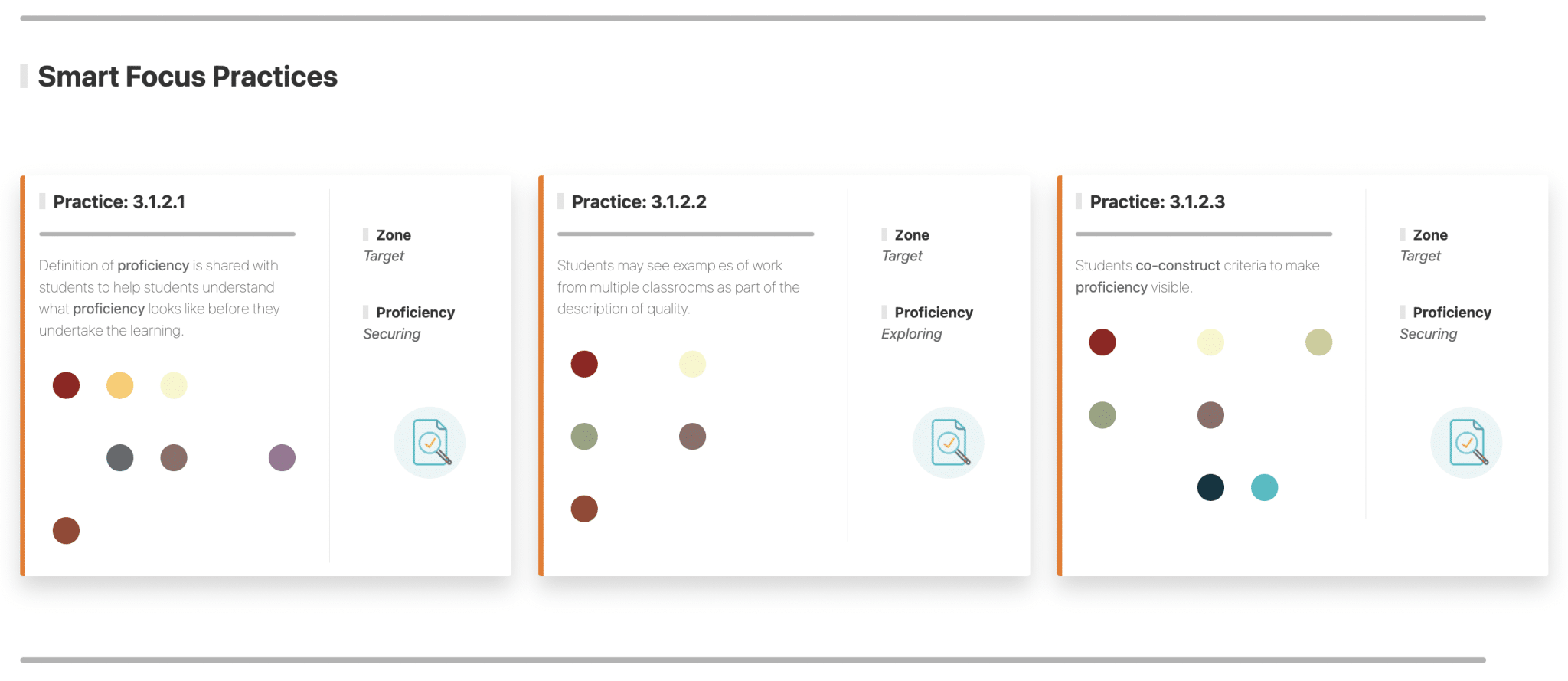

Once a learning intention is set, educators are ready to make data-based decisions for how to operationalize their goals and desired outcomes. Educators have personalized data dashboards where they are able to see their past responses, scores, and target zones in each CBE principle based on self-assessments. There are multiple ways to view and use their data, but here our example is the Smart Focus Practices that are suggested for each educator based on their self-assessments (see Figure 2).

The three Smart Focus Practices shown in the figure are:

- Definition of proficiency is shared with students to help students understand what proficiency looks like before they undertake the learning;

- Students may see examples of work from multiple classrooms as part of the description of quality; and

- Students co-construct criteria to make proficiency visible.

Figure 2

The Smart Focus Practices, therefore, can be prioritized based on a problem of practice at the building, department/grade level, and/or collaborative teacher team level. Once they are selected, the next step is to develop those targeted skills by accessing a range of curated resources that match the adult learner profile. These resources can be common across a team, or they can be differentiated based on individual needs but all focused on the same learning intention. As long as there are common outcomes on a teacher team, differentiated pathways to those outcomes are empowering and can add value as educators share what they are discovering.

Teacher teams will ask key questions as they are moving through this Access phase:

- On which practice(s) will you focus your learning? What is your inspiration or “why”?

- How will these practices support your learning intention? With which learners?

- Which tools, resources, and people will you utilize to access the learning you need?

Then educators will transition to the Engage phase, where they will ask another series of questions:

- Which processes, activities, and people will keep you motivated during this learning process?

- How will you practice self-care?

- How long is your design sprint (weeks, months)?

- What milestones will mark progress?

- How will you stay on track?

Adult learners then transition into the “doing” part—trying new practices in context with young learners. This is the Express phase where they use new tools, resources, strategies, learning experiences, and/or peer-to-peer or group interactions. They also Iterate and Reflect, or try new learning activities more than once, often after peer observation and receiving feedback. This process helps to make old habits and practices visible and to reinforce desired shifts.

These steps are a paradigm shift. Adult learners often have others in their buildings or districts who lead them through learning activities or processes and who determine timelines and check-ins. To be successful with this shift in professional learning, the legwork outlined in Parts 1 and 2 of this series are not just “nice to have”; rather, they are integral to preparing adult learners to be successful and to young learners reaping the benefits of that success. Some districts further incentivize educator-driven learning cycles by allowing them to be part of teacher evaluations or a micro-credential process toward advancement on the salary scale or toward new leadership roles within the school or district.

Where do educators go from there?

After engaging in a professional learning cycle, educators spend some time reflecting on outcomes using learner work samples, learner feedback, and artifacts such as pictures, videos, and templates. Questions they ask include:

- What evidence is there to support that learning experiences and teaching strategies were inclusive, relevant, challenging, engaging, and focused on the success of all learners?

- How did you know when a strategy was (or wasn’t) working?

- What role did reflection play? What role did peer-to-peer feedback play?

- How would you rate your current proficiency level with your selected practice(s) from your learning intention?

Then, as teams transition to the Evolve phase, we encourage schools to engage educators in celebrations of learning to share their reflections, their successes, their discoveries, and where they are going next. Some guiding questions for this celebration of learning include:

- What did your students do/say/ask that surprised and delighted you?

- What is something you tried/felt/learned that made you proud of yourself and your team?

- Where is your learning journey and the needs of your learners taking you next?

These celebrations of learning have been powerful and incentivizing. Often we hear teams ask how they can adapt what another team tried to their own context or grade level. There is always laughter. There is often awe—awe for what their fellow educators accomplished and awe for what young learners were capable of doing or learning or designing or improving. It is the celebration of learning that reinforces the value of putting educators at the center of their own growth and empowering them to make data-based decisions for the next right step.

To be successful with this shift in professional learning, the steps outlined in all three parts of this series are essential. The web-based solution we are using provides for vision (our roadmap), consensus (addressing values and developing shared goals), skills (discrete instructional practices that can be stacked to create change), resources (e.g., micro-credential learning experiences, videos, websites, protocols, and templates), incentives (as described in this blog post), and action plans (shared or individual). If you want to know more, please contact me to discuss how I can support you and your school or district with this type of solution outside of Iowa.

Learn More

- A Roadmap for Personalized, Competency-Based Professional Learning

- Designing Data-Driven Personalized Pathways for Professional Learning

- Update on Iowa: Multi-Stakeholder Leadership

Andrea Stewart is the Director of The Center, with 11 years in personalized, competency-based learning and 24 years in education. She leads transformational change with schools, districts, education service/state agencies, higher education, and via national conferences and cross-state partnerships/consultation. Andrea served on the Iowa Department of Education’s CBE Task Force, CBE Collaborative, and Design Team, where she led the state’s competency design and assessment process. Her work in competency-based education began in 2011, when she led pilot implementation of standards-based assessment and reporting and competency-based education. Prior to this work, Andrea taught high school English for 12 years.

Andrea Stewart is the Director of The Center, with 11 years in personalized, competency-based learning and 24 years in education. She leads transformational change with schools, districts, education service/state agencies, higher education, and via national conferences and cross-state partnerships/consultation. Andrea served on the Iowa Department of Education’s CBE Task Force, CBE Collaborative, and Design Team, where she led the state’s competency design and assessment process. Her work in competency-based education began in 2011, when she led pilot implementation of standards-based assessment and reporting and competency-based education. Prior to this work, Andrea taught high school English for 12 years.