Pandemic Pods, Personalized Learning, and the Future of Education

CompetencyWorks Blog

When school buildings closed in the spring of 2020, some families created refuge for groups of displaced learners in living rooms, basements, and backyards across the country. Finding rare opportunity to remake the learning experience however they saw fit, some created bespoke learning environments reflecting the hallmarks of personalized, student-centered learning. Literally, they met children where they were.

When school buildings closed in the spring of 2020, some families created refuge for groups of displaced learners in living rooms, basements, and backyards across the country. Finding rare opportunity to remake the learning experience however they saw fit, some created bespoke learning environments reflecting the hallmarks of personalized, student-centered learning. Literally, they met children where they were.

Drawing on two years of research on the “pandemic pod” movement, a new report from the Center on Reinventing Public Education, Crisis Breeds Innovation: Pandemic Pods and the Future of Education explores what occurred when families were free to design the learning experience absent the typical architecture of school, and what it means for the future of education.

Several of the report’s findings suggest how system leaders might pursue personalized, student-centered learning in their own schools and districts moving forward.

Families value personalized, student-centered environments.

Nearly half of the pod families surveyed said they experienced more individualized instruction that met their child’s needs compared to their schools before the pandemic. In follow-up interviews, family members and instructors described environments in which children felt more seen and heard, learner interests impacted what and how learning occurred, and schedules flexed so that educators could provide the attention and resources that each child needed in the moment.

Not every pod made space for personalized learning – a finding particularly evident in pods that relied more heavily on remote learning provided by schools. But families that reported more personalization felt more satisfied by their experience: 85 percent of these families felt their pod was overall better than their child’s pre-pandemic schooling, compared to just 16 percent of families that experienced less personalized learning in their pod.

Relationships drive learning.

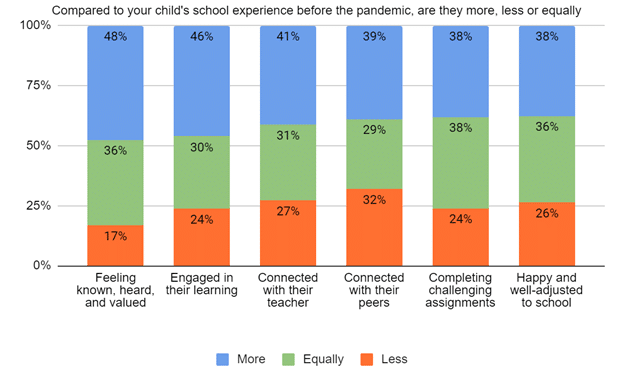

When asked how their child’s experience compared to their prior schools, many families pointed to the pod’s intimate relationships as a key advantage. More often than any other benefit they cited, 48 percent said that their child was more likely to feel known, heard, and valued in the pod compared to their previous schools.

One parent contrasted the personal attention each student received in her pod with the “anonymity” of her child’s former school: “Every kid that’s here, they’re here and they feel their space,” she said. “There’s no getting lost in this.”

Instructors also commonly described their ability to form closer relationships with students in ways that benefitted instruction. Said one pod instructor, “I only had a small group of students that I was focused on, which really let me see what they needed help on [and] what pieces of information and knowledge they were missing.” Others described pivotal moments in which their ability to devote attention to one student at a time enabled them to try multiple strategies until mastery was reached, or to notice changes in students’ dispositions and provide just-in-time support for social and emotional skill development.

Families contribute to and benefit from personalized environments.

Learners weren’t the only ones whose needs were centered by pods; families were too. Over 80 percent of the pods in our sample were self-organized by families, meaning they had unprecedented ability to design the learning environment however they saw fit.

Families used their newfound agency to get more involved in their child’s learning. Compared to their child’s prior schools, nearly half of families said their pod gave them greater insight into their child’s learning and more influence over what and how their child learns. And these families were more than twice as likely as other families to say they trusted pod instructors more than they trusted their child’s teachers before the pandemic.

Instructors, too, felt the benefits of deeper relationships with families: nearly 2 in 3 said they were more likely to form supportive relationships with families in service of their children’s learning than in their prior work experiences. In the words of one instructor, her deeper relationships with families gave her “a better view of these students, so I feel like I’m making more of a difference.”

For some families of color, their heightened influence allowed them to tailor the learning environment in ways that affirmed their child’s identity and family history. One Black parent said:

“We got to choose the books that they’re reading and the projects that they’re doing. And we got to have say-so in voting on their curriculum. And that level of empowerment to parents is something that we do not see in many areas where you have to fight for [representation], or you still might feel marginalized in larger settings. . . It’s been amazing to be able to prioritize what we felt was important.”

Some families even used the opportunity to hire instructors that reflect their background. For example the Black Mothers Forum in Phoenix, Arizona intentionally recruited Black mothers with formal degrees in K-12 education to serve as Learning Guides for their pods. The Black parent quoted above did the same for her pod, noting that “all of the parents have been so excited at being able to choose who is teaching our children, having that level of control, knowing who this person is, picking somebody from the community… building and deepening a relationship with them and knowing that they’re invested in our children as individuals and as people.”

All kinds of educators can promote learning, but they need to be let in.

According to families surveyed, nearly 80 percent of pods relied on certified school teachers to provide at least some math and ELA instruction remotely. This unique arrangement gave families unprecedented opportunity to seek out pod instructors with diverse skillsets that complement remote instruction to better meet the needs of their students.

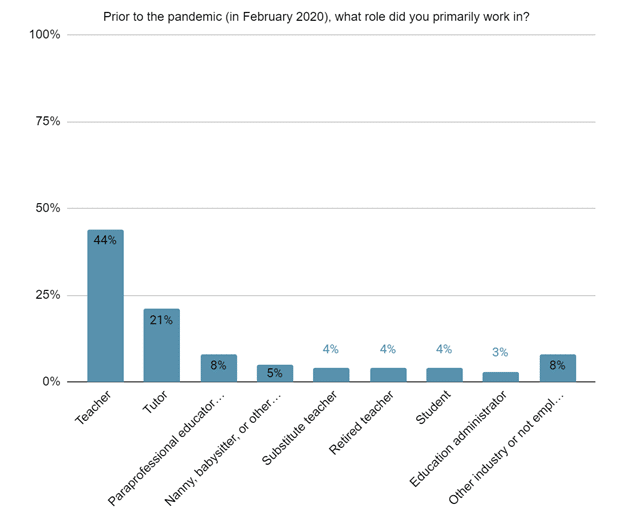

More than half of the pod instructors we surveyed were not teaching right before the onset of the pandemic. Instead, they were working as tutors, childcare providers, paraprofessional educators, or were former teachers who came out of retirement. Many of these educators did not have teaching certificates, but they brought other skills to the table—like the former camp counselor with a knack for building relationships or the architect and carpenter who engaged students to apply their math skills by building a treehouse in the backyard.

One instructor had lost her job as a school bookstore coordinator during the pandemic, but when she learned about pods she immediately felt she had something to contribute. “I said, ‘Hey, this is my background.’ I homeschooled my kids for 17 years… I have a BS in human development and a BS in art education.” She went on to observe that not many certified teachers appeared willing to manage multi-age groups in pods, but “when you’re a homeschooler, that’s what you do constantly.”

However, while some pods were able to achieve seamless collaboration between pod instructors and credentialed teachers providing remote learning, some families and instructors encountered resistance. Some said their districts actively discouraged school leaders from collaborating with pod instructors and prohibited them from making any special accommodations like allowing pod children to attend the same virtual class. One instructor described receiving clear signals from the school that “they don’t want you interfering with the teacher’s time… You can help, you can support, but stay in your lane.”

The Road Ahead

Even though nearly 3 in 5 families and 3 in 4 instructors preferred their pod over their child’s pre-pandemic schools, the costs of podding and the challenges of operating off-grid propelled most families back to their prior schools once buildings reopened. But for some, their learner-centered experiences in pods changed how they think about education and what they want from schools moving forward.

In the end, the best way to learn from pods may not be to hope that the structures themselves will endure, but to allow lessons from podding to influence how schools and districts pursue their own transformations toward personalized, learner-centered education. Implications for school and district leaders include the following actions:

- Restructure staffing to foster deeper relationships. Pods reinforce the centrality of deep human relationships in creating learning environments that are truly tailored to each child’s strengths and needs and can support them to reach mastery. System leaders should not rest on technological solutions that personalize content delivery without fundamentally rethinking how new staffing structures and systems of support can better enable every child to feel known, valued, and supported. For example, some schools and districts designate some staff as mentors or advisors, setting up crews or advisory systems that deepen connections between adults, students, their learning, and the broader community.

- Extend agency to families, not just students. Pods demonstrate that learners do not exist in a vacuum but are embedded within rich family and community contexts that can contribute to, and also benefit from, a more personalized approach to learning. Just as student-centered models extend learners the agency to shape their learning journeys, so too should system leaders consider how they might increase opportunities for families to help shape their child’s learning environment. This could mean including parents and caregivers alongside teachers and students in advisory teams, or designing a more participatory school governance model.

- Create strategic teams of educators with diverse backgrounds and skillsets. Now more than ever, school leaders recognize the multitude of roles and responsibilities that educators carry, each requiring different expertise and skillsets. Rather than expecting any one educator to master all of the competencies needed to create personalized, learner-centered environments, system leaders should consider how to build teams of educators with complementary backgrounds and skillsets. Pods suggest that this can be done in ways that also diversify the pool of educators, drawing in the wealth of assets that currently exist outside school walls.

While widespread podding may not last beyond the pandemic, many families and instructors who participated in them retain fond memories of how their pod deepened relationships, forged community, provided flexibility to meet individual needs and interests, and created joy. Some parents went so far as to call their experience a “year of paradise” and a “momentous occasion in childhood.” System leaders should learn from what pandemic pods got right so that any family, anywhere may be able to make such claims about their child’s learning.

Learn More

- Crisis Breeds Innovation: Pandemic Pods and the Future of Education

- Why Should Schools Transition to Competency-Based Education?

- Meeting Students Where They Are

Jennifer Poon is a freelance education consultant and Fellow with the Center for Innovation in Education, supporting education leaders to design systems that adapt to the unique needs and interests of all learners, especially those most historically underserved. Her professional perspective has been shaped by her time as a high school biology teacher and volleyball coach in South Central Los Angeles. She has also served as research director and director of the Innovation Lab Network at the Council of Chief State School Officers. She holds a B.A. in molecular and cellular biology from Harvard University and an M.Ed in teaching and curriculum from Harvard Graduate School of Education.