Whose Standards Are We Privileging? Collaboration and Consultation with Indigenous Leaders

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second of two blog posts by Jerad Koepp and Michael Smith. The first post is here.

In this blog post we investigate the practices and policies needed to develop and sustain relational trust with Native leaders. This will increase awareness of the needs and desires of your local Tribal community, allowing progressive practices such as Tribal-based competency crediting to occur. Information presented may be used as a model for school leaders to follow. We, as education leaders, must always consider how past interactions of the local Tribal community with non-Tribal school officials may limit a Tribe’s readiness for enacting change. Educational leaders must utilize meaningful and intentional practices towards unifying communities focusing on healing and positive relationships. This process is multi-level and requires educating teachers, administrators, and students.

A vital component of competency-based learning is an understanding of how education standards are embedded into real-life learning opportunities. Under this paradigm, competency is measured by a student’s ability to demonstrate knowledge in authentic settings, without the constraints of formal coursework. Two highlights of the Aurora Institute’s revised definition of competency-based learning—the recognition of a student’s culture as a vital element of learning and encouraging different learning pathways—are relevant to Tribal competency crediting.

When working alongside Indigenous communities, educators must be aware that Indigenous students function with “a foot in each world.” Standards for learning within the Indigenous community may not be reflected in state/district standards. Native communities have their own standards of learning for their children; standards that school leaders must take into consideration when developing a mastery-based learning system. Without knowledge of and authentic partnerships with your Indigenous community, school leaders will continue to be incapable of understanding and navigating the full spectrum of stakeholder needs and desires. This level of knowledge requires intentionality, humility, patience, and a significantly different leadership approach by school leaders.

Our Story: Knowledge and Access

Jerad Koepp serves as North Thurston Public Schools’ Title VI coordinator. Title VI is a federal program developed to support the unique cultural and academic needs of Native students. One of the many duties of a Title VI coordinator is to facilitate consultation and collaboration between Indigenous communities, parents and students, and public school employees. Your district’s Title VI coordinator holds a wealth of knowledge regarding your local Indigenous communities.

Several years ago Mike asked Jerad to present to one of his all-staff meetings followed by a breakout session. At that time, Jerad hadn’t interacted with Mike much more than hallway pleasantries. Jerad appreciated what it was at the time, the uncommon opportunity for such a large and focused audience. Jerad’s short overview and data presentation made an immediate difference in increasing Native student visibility in the high school.

One day, Mike asked to meet with Jerad a couple of times to teach him everything about Native education. It was a big ask but Mike’s character and professional approach were different from what I had been used to from administrators. Rather than the typical short attention span, clear distraction, or adhering to a tight time schedule, Mike settled in. He wasn’t looking for easy answers or tasks to check off for a school improvement plan. As expected in social justice work, Mike was showing up to “do the work.” Mike made it clear where he stood as an ally and was committed to taking meaningful action to improve the education experience for Native students. Mike heard hard truths and asked tough questions of Jerad, Tribal leaders, and Native families. Mike set out on a journey to earn trust from our communities and demonstrate his commitment. The work we all engaged in has helped our district become a model of Tribal collaboration.

Understanding Sovereignty and Self-Determination

The importance of the traits of humility and humbleness can not be understated when seeking to gain knowledge and understanding of the experience of local Tribal members in public schools. As educational leaders, we must listen to our stakeholders, free of judgment or preconceived notions. Having the basic understanding of sovereignty and self-determination will assist you in developing relationships, but always being humble about your lack of knowledge of the local Indigenous peoples will assist in sustaining relationships. Sovereignty is the inherent and unceded right of Native people to self-govern. It is ever-evolving and continues to face challenges. It also ensures that any decisions about Tribes are made with their participation and consent. Educational sovereignty is the ability for Tribes to create, develop, and provide an education system that best advocates, supports, and sustains the culture, norms, languages, and values of Tribal communities and people. The Indian Self-Determination and Assistance Act of 1975 allowed Tribes greater autonomy in assuming and administering government programming, including education.

Consider Your Leadership Style

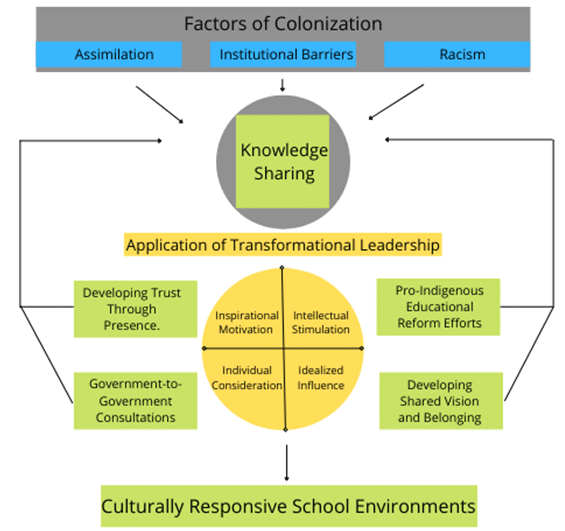

As a public school leader, you are tasked with assisting in Nation building. The goal of Nation building is to understand the needs of your local Indigenous Tribe and change educational practices to strengthen and sustain their community. In your interactions with Tribal leaders, it is important to listen and engage with leaders transparently, avoiding the use of transactional leadership methods or behaviors. While forms and surveys need to be completed to secure funding, the approach and relationship make a difference in how Native leaders perceive your intentions. Consider adopting a transformative leadership stance within your practice, as it is in greater alignment with many Indigenous community values. A framework for transformative leadership is shown in the figure below.

Local Actions: What Have You Done for the Community?

In the Spring of 2018, The Nisqually Tribal leaders entered into conversations with educational leaders at North Thurston Public Schools. The goal of the conversations was to start building meaningful relationships, create pro-Indigenous imagery, and implement a formal government-to-government system of communication. Under the leadership of Superintendent Debra Clemens, and Nisqually Tribal Council members Willie Frank (Chair) and Hweqwidi Hanford McCloud, Jerad and Mike were allowed to bring the relationship between the Nisqually Nation to a new level.

Gatekeeping is the leadership process that seeks to micromanage innovation. For highly skilled and competent leaders, gatekeeping is one of the most harmful acts, because it stalls reform efforts from taking place. Superintendent Clemens prevented gatekeeping from occurring, allowing vital work to be completed in making North Thurston Public Schools a more equitable place of instruction for Native students. Due to her leadership, personal ethics, and understanding of cultural competencies, the following unprecedented actions and policies occurred, starting the process of healing and reconciliation:

Equity Resolution: The first of these actions was the adoption of an equity resolution by the North Thurston Public Schools. It provides a framework for engaging in critical work to remove systematic barriers in education for Black, Indigenous, and people of color. Believing in equity drives action. The creation of a district equity resolution provides an opportunity for school districts to formally recognize areas of growth needed to better serve students, faculty, and the community.

School Employee-Tribal Leader Exposure: One of the first practices implemented was getting Tribal leaders on campus, sharing their perspectives and stories. It was also vital to get school employees on Tribal lands to understand the importance of traditional teachings and Indigenous “ways of being.” Consider inviting Tribal leaders to share their perspectives, history, and culture with your students and staff. This is also a great opportunity to create community celebrations to honor your local Tribe and the contributions they have made to your community.

School Programming: The strides being made in the systemic change needed to carry over into the classroom. Mike approached Jerad to develop, train staff for, and support what would eventually become a Native Studies program. Understanding the significance of the opportunity, Jerad went about co-developing a rigorous course of study that moved beyond being culturally responsive to creating classes that were culturally sustaining and revitalizing. These courses don’t merely teach about Native people, they also teach with Native people, utilizing an increasing amount of decolonized pedagogies. These are critical competencies because courses like these are also intended to help build Tribal capacity and future leaders. To facilitate this, Native students are actively recruited and have enrollment preference in the courses.

Flags/Land Acknowledgement: Visibility matters. Native peoples have existed on our lands since time immemorial. One of the more significant actions taken by North Thurston Public Schools was working collaboratively with the Nisqually Nation in developing a statement of land acknowledgment and hanging the Nisqually flag at each of its 23 school buildings. Land acknowledgements are read at formal events, sporting events, and any other time the pledge of allegiance or National Anthem is played.

Government-to-Government Consultations: School and Tribal leaders should be in communication and consultation regarding the educational progression of Native students. Consultation meetings are a wonderful opportunity to hear about the needs and desires of your local Tribe. They are also great opportunities for school officials to share progressive policies, progress towards implementation of practices, program reviews, and opportunities for student advancement.

Public School Systems That Recognize Indigenous Community Standards of Learning

Through the creation of authentic relationships, school leaders can inquire about student programming that Tribes offer their children. Tribes often host cultural and educational programming that focuses on building sustainable Indigenous Nations. School leaders should consider developing a local memorandum of understanding recognizing the cultural and educational benefits of Indigenous community programming. Often Indigenous programming includes art, history, cultural activities, language, business, civic engagement/leadership, and natural resources. An agreement made to honor these systems of education will result in a greater school-to-home connection, as well as increased rates of Native student success in public schools.

Public school officials must honor the learning and education systems developed by their local Indigenous communities. Mastery-based crediting provides a viable pathway to recognizing Tribal education systems as valuable to the health and well-being of our larger education community. Learning about the needs and desires of your local Tribe requires education leaders to work on creating authentic relational trust and comprehensive systems of government-to-government consultation.

Learn More

- A Primer to Indigenous Education: A Case for Tribal Competency Crediting

- The First Steps Forward: One District’s Focused Effort to Provide Native Students With an Equitable Education

- Designing for Equity: Leveraging Competency-Based Education to Ensure All Students Succeed

Jerad Koepp (Wukchumni) has 12 years of professional experience in Native American education. He has been recognized as 2022 Washington State teacher of the year and 2022 ESD 113 regional teacher of the year. Jerad earned his Master’s in Teaching from the Evergreen State College, specializing in Native Education, and is certified in history and social studies. Since 2013, he has proudly served as the Native Student Program Specialist for North Thurston Public Schools, providing cultural and academic support for approximately 250 Native American students from over 50 Tribes, nations, bands, and villages. He also trains and supports district staff, serves as a liaison to local Tribes, and leads the development of his district’s growing Native Studies program. Jerad serves on the board of the Western Washington Native American Consortium as secretary. He has made presentations to many professional groups and has played a key role in creating district policies supporting Native education, culture, and students.

Jerad Koepp (Wukchumni) has 12 years of professional experience in Native American education. He has been recognized as 2022 Washington State teacher of the year and 2022 ESD 113 regional teacher of the year. Jerad earned his Master’s in Teaching from the Evergreen State College, specializing in Native Education, and is certified in history and social studies. Since 2013, he has proudly served as the Native Student Program Specialist for North Thurston Public Schools, providing cultural and academic support for approximately 250 Native American students from over 50 Tribes, nations, bands, and villages. He also trains and supports district staff, serves as a liaison to local Tribes, and leads the development of his district’s growing Native Studies program. Jerad serves on the board of the Western Washington Native American Consortium as secretary. He has made presentations to many professional groups and has played a key role in creating district policies supporting Native education, culture, and students.

Dr. Michael Smith has served in public education for the past 15 years, ten of which have been in school administration. Currently he is the principal of Rochester High School in Rochester, Washington. For the past five years, Michael has worked alongside Native leaders in Washington State to bring forth sustainable educational change for Indigenous communities. His doctoral dissertation focused on Indigenous leaders’ perceptions and experiences working with educational leaders, identifying the skills and dispositions required to lead transformative change. He has been fortunate enough to share his research with colleagues through local, state, and National conferences and writings. Michael is supported by his wife, Ashleigh, and his loving daughter, Avileigh. If you want to collaborate or know more, Michael welcomes you to email him at [email protected]

Dr. Michael Smith has served in public education for the past 15 years, ten of which have been in school administration. Currently he is the principal of Rochester High School in Rochester, Washington. For the past five years, Michael has worked alongside Native leaders in Washington State to bring forth sustainable educational change for Indigenous communities. His doctoral dissertation focused on Indigenous leaders’ perceptions and experiences working with educational leaders, identifying the skills and dispositions required to lead transformative change. He has been fortunate enough to share his research with colleagues through local, state, and National conferences and writings. Michael is supported by his wife, Ashleigh, and his loving daughter, Avileigh. If you want to collaborate or know more, Michael welcomes you to email him at [email protected]