Pathways, Pacing, and Agency Are Intertwined

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the third post in a series about the Chugach School District in Alaska. Links to the other posts are provided at the end of this article.

The Whittier Community School provides many opportunities for three core components of competency-based schools: different pathways, varied pacing, and student agency. Before sharing some of their strategies, it’s worth revisiting the nuances of those terms:

The Whittier Community School provides many opportunities for three core components of competency-based schools: different pathways, varied pacing, and student agency. Before sharing some of their strategies, it’s worth revisiting the nuances of those terms:

Different Pathways – Students in competency-based schools can master learning targets in different ways, in different orders, and at different ages, reflecting their unique needs, strengths, interests, and goals. These differences should not be mistaken for the inequitable, traditional practice of tracking.

Varied Pacing – The primary goal is deeper learning, not faster learning. Varied pacing can mean that students who are proficient in certain standards are encouraged to engage in ways that lead to greater depth of knowledge and multiple ways of demonstrating competency. Varied pacing does not imply that there is a single learning pathway that students simply navigate at different speeds. Each student’s pace of progress matters, with schools actively monitoring progress and providing more instruction and support if students are not on a trajectory to graduate by age 18 or soon after.

Student Agency – The methodical development of both the capacity and the freedom of learners to exercise choice regarding what is to be learned and to co-create how that learning is to take place. This has four components—setting advantageous goals, initiating action toward those goals, reflecting on and regulating progress toward those goals, and a belief in self-efficacy (source: this Education Reimagined blog we cross-posted in August).

Individual Learning Plans

Whittier’s learning strategies illuminate connections among these three aspects of competency-based education. All Whittier students have Individual Learning Plans (ILPs) that serve two main purposes. First, students do not always demonstrate mastery on particular standards during the time that those standards are the focus of group instruction in a class. ILPs provide opportunities for students to revisit those standards. (It’s important to say that teachers in competency-based schools often lead students through learning activities in groups, which is not only efficient but has educational advantages. Thinking that every learning experience must be entirely individualized is a misconception that can lead various stakeholders to doubt that competency-based education is possible.)

Second, ILPs are a structure for students who want to meet standards in personalized ways or go beyond “meeting” standards to “exceeding” them. Specific times during each school week are set aside for students to work on ILP projects.

Whittier parents who work in the local fish processing plants have their prime earning months in the summer, so they sometimes return to the Philippines for several weeks in the winter to visit their extended families. Their children are out of school during these visits, and ILPs allow them to continue making progress while they’re away and to make up missed work once they return.

One student completed an in-depth project about the history, politics, culture, and language of the Philippines in preparation for her trip, fulfilling culture and communication standards. Her teachers emailed her some assignments while she was gone, although they wisely set boundaries on these accommodations, which can explode into an unmanageable workload for the teacher. The student was also able to catch up on other standards during ILP times when she returned. Of course there were some standards that she simply couldn’t complete, but the school’s structure meant she could complete them in future school years without having to “stay back” a year or redo entire courses in which she had already demonstrated mastery of many of the competencies.

Another student’s ILP was based on her strong interest in composting worms, which led to a two-year project that met standards on environmental science and project planning, implementation, and presentation. She researched how to set up a worm bin, learned what they could and couldn’t eat, built the bin, ordered the worms, and kept them fed in the art room. When she learned that the worms could compost human waste, she integrated them into her family’s outhouse to work their magic during the warmer months before they froze during the Alaska winter.

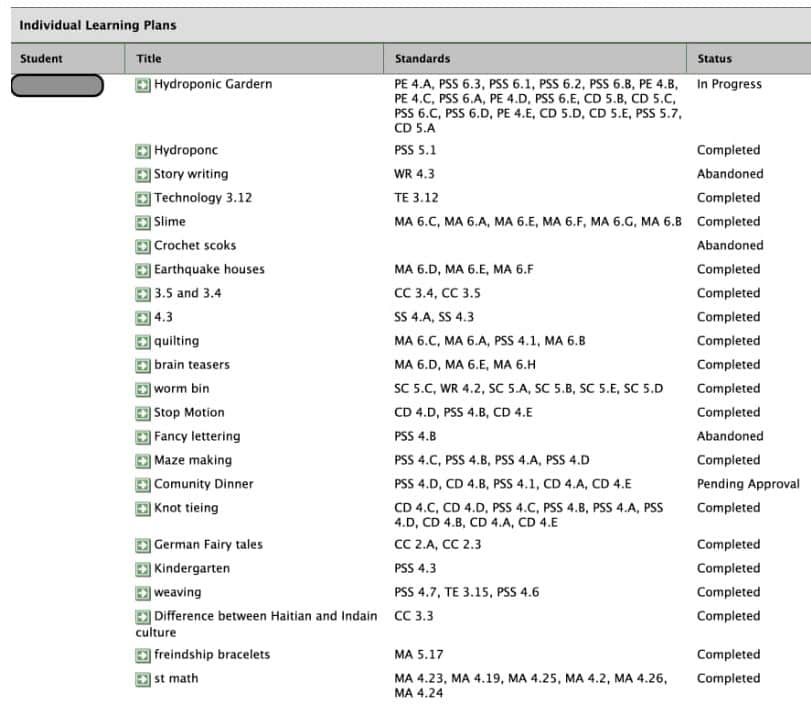

An advantage of some ILPs is that they put students and their interests in the driver’s seat, giving them alternative ways to demonstrate mastery of some standards. (Whittier teachers use many standard curriculum resources, which, again, is not inconsistent with competency-based education.) The adjacent screenshot from Chugach’s learning management system shows one student’s ILPs during a three-year period, including the topic, standards met, and project status.

An advantage of some ILPs is that they put students and their interests in the driver’s seat, giving them alternative ways to demonstrate mastery of some standards. (Whittier teachers use many standard curriculum resources, which, again, is not inconsistent with competency-based education.) The adjacent screenshot from Chugach’s learning management system shows one student’s ILPs during a three-year period, including the topic, standards met, and project status.

Other Pathways

Whittier also offers many other activities that foreground student interests and offer diverse pathways to meeting school standards. During weekly “WIN Times” (for “What I Need”), teachers offer mini-courses on a variety of topics that are selected by asking students what they want to learn. The courses are then designed to fulfill school standards. The WIN courses taking place during my visit were drawing, arts and crafts, drama, and “learn a language.”

During the language WIN period, students were using the Duo Lingo online platform to study a language of their choice. Their choices were French, Spanish, Irish, and Japanese. The teacher facilitated each students’ progress on Duo Lingo individually and then led group discussions at the end of each period. None of the school’s five teachers are certified to teach languages other than English, but students have the option to learn languages more deeply through distance courses. The school doesn’t have a foreign language standard, but some of the culture and communications standards can be met through foreign language learning.

Students also carry out personalized service projects based on their interests that include developing a project plan, carrying it out, and making a presentation about the process and outcome. One student crocheted hats for premature babies and developed a plan about how to raise funds, buy the yarn, learn to knit, deliver the final products, and other steps. Another student volunteered at the local conservation center all day every Monday (including school hours). Other projects included running a city-wide food drive, leading the school’s annual Thanksgiving and Christmas events, and leading church activities for young children. In addition to project-specific academic content standards, these projects fulfilled aspects of the school’s Personal/Social/Service standard.

And there are many other personalized pathways. Students take online college courses, participate in a leadership summit, travel to Anchorage for courses at the Chugach Voyage School or to Tatitlek for their annual Cultural Heritage Week, or help to skin and process a black bear that was “dispatched” after getting too aggressive on the school grounds. All of these activities are based on student choice and are structured to fulfill some of the school’s standards.

With student voice and choice being so central to Whittier’s learning activities, student agency becomes deeply intertwined with varied pacing and pathways. Building this three-legged stool is a tremendous advance in any school’s competency-based practice.

Other Posts in This Series

- Rethinking Grade Levels and Age Groupings at the Whittier Community School

- Bringing Parents Into Competency-Based Schools

- Sustaining and Sharing Cultural Heritage at the Tatitlek Community School

Learn More:

- Policies for Personalization: Levels, Pace, and Progress

- What Do You Mean When You Say “Student Agency”?

- Chugach Teachers Talk about Teaching

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.