Scheduling for Personalized Competency-Based Education: Book Review and Reflections on Equity

CompetencyWorks Blog

A review of Scheduling for Personalized Competency-Based Education, a new book by Doug and Michelle Finn, extends the recent CompetencyWorks blog post series about scheduling. The Finns were early innovators in personalized, competency-based schools in Alaska and Maine and have continued advancing the field through professional development and consulting with Marzano Academies and Marzano Resources.

A review of Scheduling for Personalized Competency-Based Education, a new book by Doug and Michelle Finn, extends the recent CompetencyWorks blog post series about scheduling. The Finns were early innovators in personalized, competency-based schools in Alaska and Maine and have continued advancing the field through professional development and consulting with Marzano Academies and Marzano Resources.

Recognizing that scheduling is just one of many changes needed when implementing personalized, competency-based education (PCBE), the book focuses on strategies for schools and districts whose transition to PCBE is already well underway on factors such as defining academic standards, developing instructional strategies that build student agency, and utilizing standards-based assessment and reporting. Before launching into the specifics of scheduling, they briefly review the rationale for and primary components of PCBE, often referring readers to their comprehensive book on this topic (co-authored with Robert Marzano and Jennifer Norford in 2017).

Starting with Assessment

The Finn’s scheduling strategies assume that students will learn more when they are placed in classes with a narrow range of student competency. They argue that traditional classes—with students assigned based primarily on age—typically require teachers to support students whose competencies range across several grade levels, making adequate differentiation extremely difficult. By narrowing the range within each class, teachers can personalize learning and target student supports more effectively.

The book explains that to group students by competency levels, PCBE schools must complete comprehensive, standards-based assessments of every student in every subject area. This requires schools to have their standards clearly identified, which is therefore a precursor to the proposed approach to competency-based scheduling. Then students are assigned to classes by competency level, rather than by age.

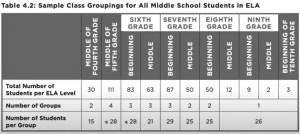

The schoolwide English language arts (ELA) assessment results for a sample middle school of 500 students are shown in the table below, which is taken from the book. The column headings represent the level of competency that each student demonstrated on the comprehensive assessments. For example, the “sixth grade middle” column shows that 63 students in the school across all age levels demonstrated middle-of-sixth-grade competency on the school’s ELA standards, and they were divided into three classes of 21 students each.

Horizontal and Vertical Scheduling

The two main strategies described are horizontal and vertical scheduling. In horizontal scheduling, all students in the school engage in similar learning at the same time, such as all students having math class during second period. This approach reduces scheduling conflicts and maximizes the ability to assign students based on their competency level and to reassign them if their learning needs change—such as if they change levels in a content area. Horizontal scheduling assumes teachers are certified to teach across multiple subject areas, making it better suited to elementary schools.

Achieving pure horizontal scheduling is difficult, because of schedule variations for students (e.g., lunch times, electives, pull-outs) and teachers (e.g., prep periods), as well as the need to share limited resources (e.g., physical education or science lab facilities). However, it can work well for a small number of prioritized subject areas that a school selects, typically based on student data and the demands of state standardized assessments. After students are assigned to those prioritized areas, pragmatic considerations such as those just discussed result in students being assigned in less homogeneous mastery groupings for other academic disciplines.

In vertical scheduling, each academic subject is offered throughout the school day. This works better in secondary schools, where teachers are typically certified in just one or two academic disciplines. As with horizontal scheduling, students are assigned to classes based on their competency level, and the schedule can typically be optimized for two high-priority academic disciplines, after which other considerations result in more heterogenous mastery groupings.

As with so many aspects of PCBE, fully transitioning to scheduling that supports competency-based education can take multiple school years. “Any approach to transitioning to a PCBE schedule is many-tiered and complex,” the authors explain. “It also involves some degree of ambiguity, which, though part of all major change, can be a powerful distractor and halt progress, causing schools or districts to wait for the ‘right’ answer….The thought, ‘We will not move forward unless we have a perfectly designed process,’ is unrealistic and also drains important focus and energy from the purpose for implementation the staff identified in the first place—positively affecting students….Do not let perfect be the enemy of the good” (p. 46).

Equity Considerations in Mastery-Based Grouping

An important question about this scheduling approach is how grouping students by competency is different from tracking. The book offers an example of teaching 7th-grade math content to a class of 6th-, 7th-, and 8th-grade students who were placed together based on their demonstrated competency. Would this class “be considered a ‘low’ class or a ‘high’ class?” the authors ask. “Neither. It would be considered a mathematics class that fills the needs of the students who are taking it” (p. 18). Clearly this class is more heterogenous than a typical tracked class because it contains “advanced” 6th-graders, “on grade-level” 7th-graders, and “below grade-level” 8th-graders. (It’s difficult to write about these issues concisely without invoking some of the same concepts we’re trying to move beyond.)

Continuing the discussion of tracking, the authors say, “Scheduling students based on their learning needs does not mean that some students are classified as low performing and tracked into a less challenging scope and sequence with no chance to advance to another track, or some are classified as high performing and placed in a more challenging scope and sequence. Such a duality creates or hinders opportunities for students based on a predetermined interpretation of potential based on how quickly students learn. That approach to organizing students is the opposite of what PCBE is trying to accomplish. PCBE ensures all students have access to the same scope and sequence of standards, with additional time and supports or acceleration offered as needed” (p. 19).

It’s clear that the intent of the proposed PCBE scheduling approach is the opposite of tracking. Nonetheless, schools using this approach will need to be vigilant about negative impacts of mastery groupings and may need to develop scheduling variations to counteract them. In her seminal book on tracking, Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality, Jeannie Oakes says “many studies have found the learning of average and slow students to be negatively affected by homogeneous placements” (p. 7). While the students in the table presented earlier may not be homogeneous in terms of age, those in the lowest-level classes are grouped only with students who are multiple years below grade level. Doesn’t this put them at risk for some of the negative effects of homogenous ability groupings?

I emailed Doug and Michelle Finn about this, and Doug kindly responded. He emphasized that the large mastery gaps in the table are the result of traditional grading and pacing practices. During the years that a school is transitioning to competency-based education, he said, instruction for students who are well below grade level “needs to be hyper-focused on filling gaps” and moving at a “pace that challenges the student and also builds confidence in their abilities to learn the content.”

Moreover, referring to Table 4.2 above, he said, “the 4th-grade group is not stuck in 4th grade for the entire year. They only have certain 4th-grade standards that need to be addressed and then they move to 5th-grade content and then 6th-grade content, even though they may still physically be in the same classroom for a quarter, semester or school year.” He acknowledged that the lowest-performing students would initially lack exposure to higher-performing students, but “they will get focused instruction to build their esteem and allow them to learn that they can have success.” Over time, he said, as a school designs learning around a PCBE schedule, the learning gaps will grow smaller.

Many educators in competency-based schools have observed these types of outcomes, which we now need to evaluate through more formal research. The results could assure us that competency-based innovations are not perpetuating well-known inequities related to ability groupings, but we also need to be open to negative findings and refining our strategies. In the meantime, Doug said, “if a school feels that having a 4th-grade group is inequitable, which I can understand, then those students can be distributed more evenly throughout the rest of the groups. That shift would increase the range of learning needs within the other classes. The whole point of PCBE scheduling is to reduce the range of needs within a class so the teacher can focus on the learning needs and move at an appropriate pace. It is a give-and-take process, and each school needs to determine what variables are important to them.” (Another valuable discussion of these issues is in Paul Emerich France’s sections on “The Dangers of Homogeneity” and “The Limits of Heterogeneity” in his book Reclaiming Personalized Learning, pp. 32-36.)

Doug and Michelle Finn have made a valuable contribution to the field by presenting a comprehensive approach to PCBE scheduling that can be studied, implemented, and compared or integrated with other scheduling models. They have provided many practical tips, resources, and principles that can support their own and other PCBE scheduling strategies. Schools developing schedules to support competency-based education would benefit greatly from similarly comprehensive explanations of how to implement all of the PCBE strategies currently in use, such as flex-mod scheduling in Bismarck, North Dakota and the multi-age model in Harrisburg, South Dakota. (Despite some differences, these other models share important features with the Finns’ approach.)

To continue refining this essential work, we need to conduct research and share professional knowledge to identify what scheduling approaches achieve the most equitable and effective student outcomes, and what instructional and staffing models make these approaches most manageable for educators.

Learn More

- Scheduling for Personalized Competency-Based Education (the Finns’ book)

- Scheduling for Personalized Competency-Based Education (video of their session at the 2020 Aurora Institute Symposium)

- Flex-Mod Scheduling to Enable Competency-Based Learning

- Lessons from Tracking Student Flex Time in a Competency-Based High School

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.