Student Thinking Made Visible: Assessing Transferable Skills with Brief Performance Tasks

CompetencyWorks Blog

Competency-based education emphasizes learning not only academic knowledge but also skills and dispositions. These include transferable learning skills such as problem solving and effective reasoning that enable people to perform effectively in different settings and apply knowledge and skills to different tasks. A session at the recent Aurora Institute Symposium introduced valuable strategies for assessing these skills. The tools and concepts they shared could also inform assessments of other lifelong learning skills.

Competency-based education emphasizes learning not only academic knowledge but also skills and dispositions. These include transferable learning skills such as problem solving and effective reasoning that enable people to perform effectively in different settings and apply knowledge and skills to different tasks. A session at the recent Aurora Institute Symposium introduced valuable strategies for assessing these skills. The tools and concepts they shared could also inform assessments of other lifelong learning skills.

The session was led by Director of Curriculum and Instruction Jeff Heyck-Williams and 5th-Grade Teacher Katie Mancino from Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, DC, a school in the EL Education network. They emphasized that teachers typically prioritize whatever will get assessed, so it’s important to assess lifelong learning skills.

Rubrics for Critical Thinking Skills

The rubrics presented for assessing problem solving, effective reasoning, and decision making serve the essential function of providing both students and teachers with a clear picture of what quality looks like. This enables teachers to plan instruction oriented toward deeper learning with these targets in mind.

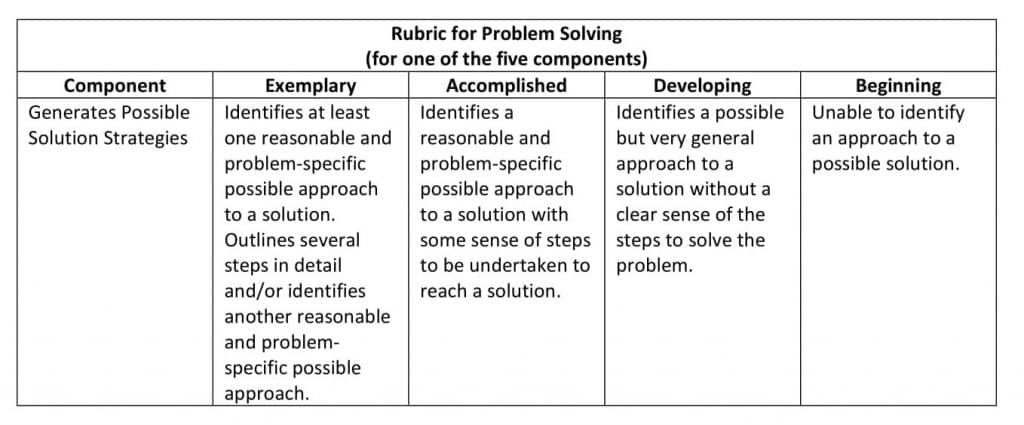

The session focused on assessing problem-solving skills, defined as “The ability to identify the key questions in a problem, develop possible plans for solving, follow through on those plans, and evaluate both the success of the plan and the solution.” The corresponding rubric has five components: Identifies What Is Known, Defines the Problem, Generates Possible Solution Strategies, and Evaluates Solutions. The table below contains the rubric for one of these components.

Three principles guided their rubric design process: (1) Rubrics define the construct that you want to teach and assess for students and teachers; (2) Each component on the rubric needs to be mutually exclusive but also narrow to a single dimension; and (3) The rubric should define a a continuum of growth from novice to expert.

Three principles guided their rubric design process: (1) Rubrics define the construct that you want to teach and assess for students and teachers; (2) Each component on the rubric needs to be mutually exclusive but also narrow to a single dimension; and (3) The rubric should define a a continuum of growth from novice to expert.

Performance Tasks to Assess Critical Thinking

With the rubric in place, the question remains of what and how to assess. Two Rivers accomplishes this with brief performance tasks that are specific to the skill being assessed. EL Education believes teachers should experience the educational approach they plan to implement with students, so unsurprisingly we were led through a problem-solving performance task. In short, small groups were given two cups, some paper, rubber bands, paper clips, and blue tape. Brief, clear instructions launched groups into creating a bridge with a maximum span using the materials provided.

For this performance task, students at Two Rivers are assessed on how well they make their thinking visible, not how good their bridge is. This is done in writing on a handout, although teachers can scribe for students who need writing support. Before starting to build bridges, our first step was a “KWI” (Know, Want, Ideas) exercise in which we had to write about “What do you KNOW?,” “What do you WANT to know?,” and “What are some IDEAS you have about how to solve the problem?”

Then we had seven minutes to begin the task (it was brief due to time constraints of the session), followed by a second round of writing on three more questions: What did you create so far? What’s working or not working? What will you try next? Again, teachers emphasize writing clearly, because making thinking explicit is a focus of the assessment. Handouts with student and teacher instructions for the performance task, plus the three rubrics, are available on the CompetencyWorks Wiki.

Three guidelines offered for scoring student work were:

- Trust the data in front of you. Just use what’s present, rather than drawing inferences that risk bias based on possible preconceptions about the student.

- Stick with the language of the rubric. If it has scores of 1, 2, 3, and 4, don’t assign a 2.8 to a student who has almost reached a 3. Just give it a 2. This is about assessment for learning, so identify the issue that’s making it fall short of a 3 and offer that as feedback that leads to additional learning.

- Score the work independently on each component of the rubric. Don’t give an average score, because this can mask competencies that need additional development. It’s fine to be in different places on different competencies.

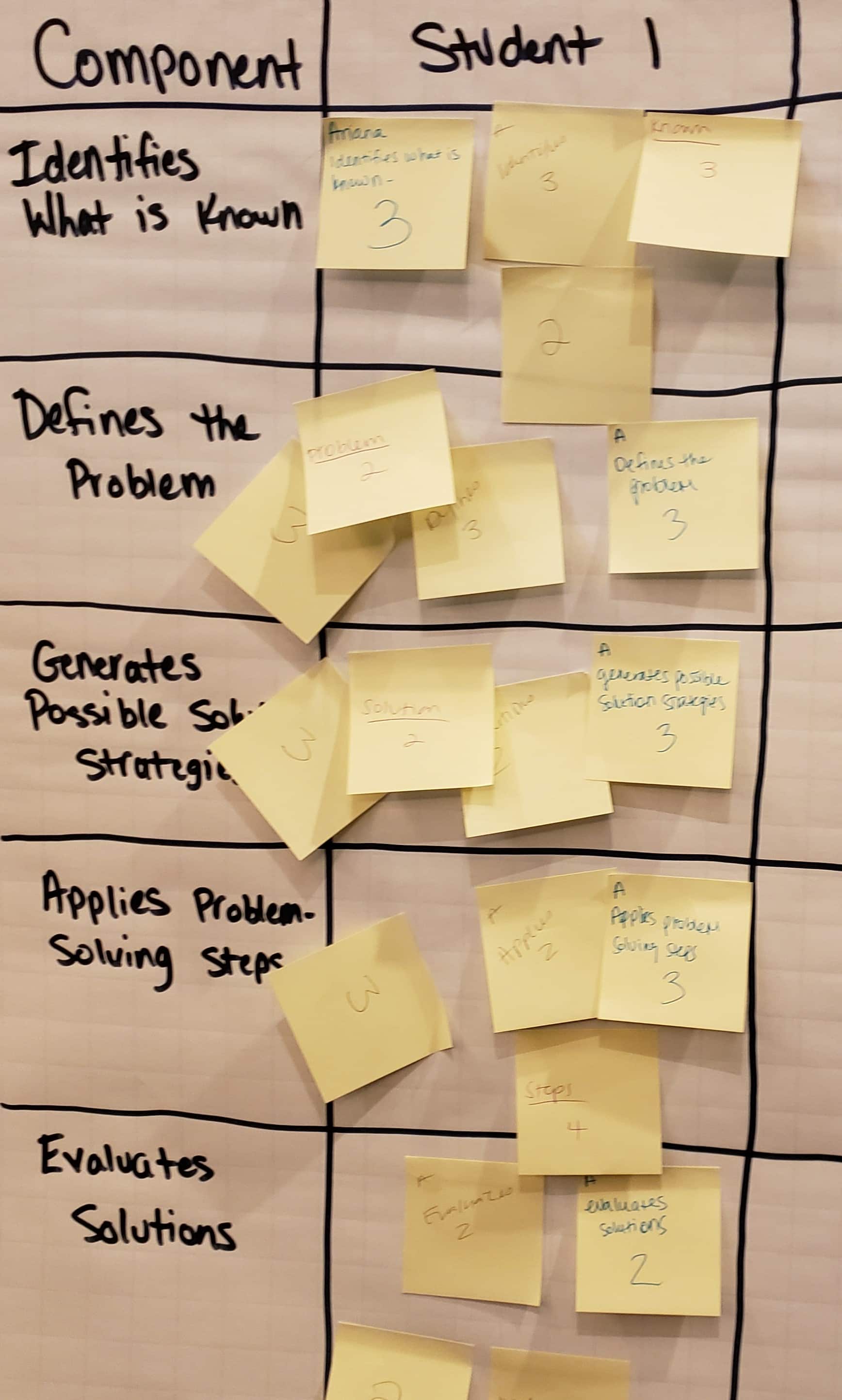

We also engaged in a calibration task based on some samples of student work on the bridge-building performance task. Groups of several attendees scored the student work, posted our scores on a butcher paper rubric on the wall (see photo), and then discussed any differences in scores. The goal of calibration is to create consistency in scoring by giving teachers opportunities to score and discuss work collectively, come to a collective final score and rationale, and develop anchor pieces that serve as references for future assessment.

We also engaged in a calibration task based on some samples of student work on the bridge-building performance task. Groups of several attendees scored the student work, posted our scores on a butcher paper rubric on the wall (see photo), and then discussed any differences in scores. The goal of calibration is to create consistency in scoring by giving teachers opportunities to score and discuss work collectively, come to a collective final score and rationale, and develop anchor pieces that serve as references for future assessment.

Mancino said that at Two Rivers teachers typically do calibration in groups of two or three, with calibration happening in larger groups only occasionally. “There isn’t enough time to score all of the work at a schoolwide level,” she explained. “Calibration is about learning to use the rubrics effectively and creating some inter-rater reliability.”

To develop effective performance tasks, it’s important for the task to match the skills being assessed, such as the bridge-building task providing clear opportunities for students to explain their thinking around problem solving. Heyck-Williams also recommended “cutting out the noise,” such as being clear in this task that students were being assessed on problem solving but not group collaboration, grammar, or drawing ability. A final suggestion was to pilot test a task before using it for a formal assessment, to be sure it’s producing the needed types of information.

An important element of the assessment approach at Two Rivers is developing “thinking routines” such as the KWI exercise used in the bridge-building assessment. When students engage in these routines repeatedly over time and across classes, they build transferable skills and are able to focus on advanced content because they have internalized sophisticated processes. Two Rivers uses the book “Making Thinking Visible” by Ron Ritchart as a source of thinking routines to use with students.

Two Rivers has made important contributions to the field’s need for better tools and knowledge for assessing lifelong learning skills. Much of their work presented here was developed as part of the Assessment for Learning Project in collaboration with Next Generation Learning Challenges and the Center for Innovation in Education. More information on how teachers at Two Rivers teach and assess critical thinking and problem-solving is available on their website.

Learn More

- Threshold Concept: Assessment Literacy

- Blast Off with the Assessment for Learning Grantees

- Promoting Lifelong Learning Skills in the Classroom: New Hampshire’s Work Study Practices

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.