What’s Personalization Got to Do with It? On the Road to College and Career Success

CompetencyWorks Blog

I am delighted to have the chance to visit the Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative in Hazard, KY and meet with educators in their Next Generation Leadership Academy this week. They are spending time reflecting on the different ways to think about college and career success. Below is my presentation on how we might begin to think about college and career success in a competency-based structure.

The districts that are part of the Next Generation Leadership Academy at the Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative have been investing in many different ways to improve their schools. These include the Appalachian Renaissance Initiative to advance blended learning, efforts to raise student voice and leadership, personalized approaches to educator effectiveness, ways of approaching children wholistically, including early childhood health and trauma-informed services, and STEM.

What’s more even more impressive is that they are building their capacity to use design – enabling districts to begin to weave all these pieces together into the next generation districts and schools.

Designing anything always starts with having a clear idea of what you want to achieve. Sometimes, this is described as a problem you want to solve or something you want to improve, such as less expensive or more cost-effective. Or it may be described as your goal, the change you want to make happen in the world.

The question we have to ask ourselves in thinking about next generation education is what we want for our graduates of high school. We need to describe the change or, if you want to use a business lens, describe the product. However, there is also a big problem we are trying to solve that will shape every step of the design process. We haven’t yet been been able to figure out how to make sure all students become proficient in grade level skills, get a diploma, or are fully prepared for college. We need to think about the elements of a system that will be more reliable.

Today, we will spend sometime thinking about the goal, the system that would reduce inequity, and what it is going to take to get us from here to there.

Doesn’t it seem like we’ve been talking about this for a long time – at least twenty years? Each time we lift our expectations or deepen our understanding, we learn some more, and the conversation starts over again.

In the next series of slides, I’m going to introduce a number of different ideas of how we define what students will need to know and be able to do to be successful in their lives beyond high school. I don’t think there is any perfect way to define it – consider this just food for thought.

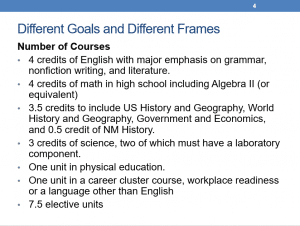

This probably looks familiar to you. We have been using credits or the Carnegie unit as a proxy of learning for 100 years. About ten or so years ago we increased expectations for students by increasing the number of academic courses they needed to take. But the problem remains – we really don’t know what students know or are able to do just because they completed a course. The courses vary in their academic level and in their rigor, teachers may grade differently, and students may get credit even though they really didn’t learn.

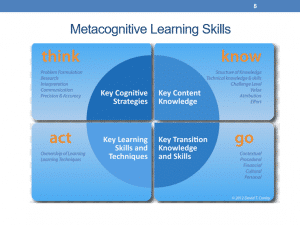

We recently came to the understanding that academic content alone isn’t sufficient for being prepared for college. We are aware that students have to have a range of other skills, higher order skills or metacognitive skills, in order to be successful. This is an example of a framework developed by David Conley and the team at EPIC trying to capture many of the so-called non-cognitive skills.

The EPIC framework has four categories of skills – in addition to content knowledgeb there is transition knowledge such as financial aid; learning skills such as ownership of learning or what is often referred to as student agency; and cognitive strategies, sometimes referred to as process skills, such as problem formulation.

I’ll take a minute here to point out a potential problem in this framework for low-income students. This framework was designed for college readiness but underestimates the importance of career development as part of transition knowledge. Students who are not exposed to careers through their family and social networks, or who might encounter discrimination in their own efforts to enter the labor market, need extra help. It is hard to imagine taking the risk of getting an expensive college education if you are not already deeply motivated by the desire and belief that you can develop a career.

I raise this as a reminder to review any frameworks through an equity lens to make sure it is going to work for all of your students.

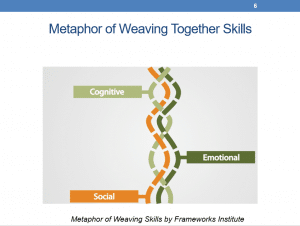

We are also now beginning to understand that social-emotional learning has a direct impact on academic learning. This is a framework released by the Frameworks Institute using the metaphor of weaving strands together to make something stronger to help explain this expanded way of understanding the skills that students learn. Your efforts to integrate trauma-informed services is really important and can be a vital step in helping students who have experienced repeated violence, disruption, or failure in their lives to build agency.

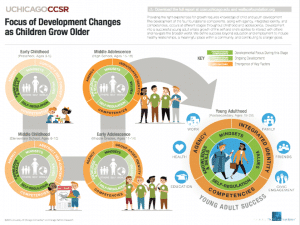

A team at the University of Chicago approached the question of what we want students to know and be able to do a bit differently by asking What do we want for young adults to be successful? They weren’t looking at it just from a K-12 perspective.

They introduce the idea that agency, competencies such as critical thinking, and integrated identity are the goal for what young people need to be successful. Underlying these three factors are four foundational components – a growth mindset, knowledge and skills, self-regulation or social-emotional learning, and values about what is important in life.

I find this framework particularly interesting for two reasons.

First, integrated identity is a very important concept, one which we often forget when we don’t make room to talk about the different experiences that African-American, Asians, Latinos, or Native Americans might have – cultural experiences, the impact of encountering discrimination, and trying to bridge different worlds. This also leaves room for how young people are growing up in terms of their gender and class.

Second, they think about this as a developmental process with different benchmarks at different ages. Again, this helps us to think about the different stages students go through on their way to developing what they need to be successful as a young adult.

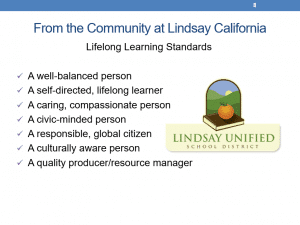

In some districts, they engage students, parents, and the community in defining what they want for their graduates. This is an example from Lindsay Unified School District, a leading personalized, competency-based school in California. Each of these items describing their expectations for their students has a detailed description of what this means. It is also driving how they are redesigning their school.

I often see the phrase “lifelong learners” rather than “college and career readiness” used in districts that engage their community. Community members tend to develop much broader expectations than educators working in isolation will.

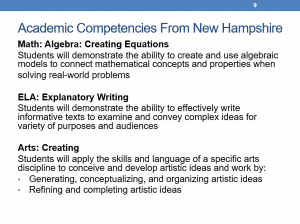

Increasingly, we are hearing of states, districts, and schools defining graduation requirements by a set of competencies. Here are examples from New Hampshire’s graduation competencies. These are the big goals they want student to know and be able to do. The standards are then aligned with these big goals for each grade or academic level. They also have work-study competencies such as communication and creativity.

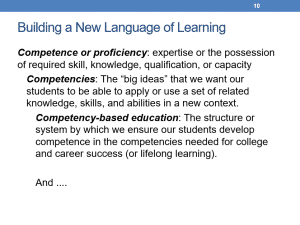

Let’s pause here for a minute to talk about this new language of learning that is being developed. It is sometimes confusing as we try to figure out new terms, clarify the meaning, and understand what it means to operationalize.

One of the most confusing is competency. To help me keep it straight, I think of being proficient or competent as an adjective, competency as a noun, and competency-based education as a phrase describing the structure or system.

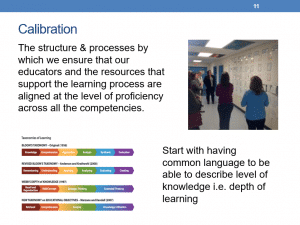

A fourth term we have to get comfortable with is calibration or tuning. Because even if we define the competencies, we still have to make sure that educators understand what it means for student to demonstrate proficiency. This usually happens in professional learning communities or departments. To build a shared understanding of writing at the different academic grade levels at Memorial Elementary School in Sanborn New Hampshire, they set up a wall with all the academic levels with samples of student work and then placed stars to indicate how many students in each grade were writing at each academic level.

I would argue that one of the reasons we haven’t been able to get sustainable agreement on what college and career readiness really means is that we haven’t tried to embed calibration into districts and schools. We depend on NAEP to tell us how our understanding of what is proficient varies or ACT rather than expecting educators to have this as part of their professional knowledge. This is a tremendous change to embed this knowledge within schools.

There is a lot of conversation about what the difference is between a competency and a standard. Competency implies that you can transfer the knowledge or apply it to a new situation. It implies higher order skills. If we just relied on standards, first of all it is too easy to start to thinking of them in a linear sense as they are written that way. One of the problems in the first year of a competency-based structure is that teachers turn to worksheets, marching students through the standards. The second thing is that the granularity of the standards can create difficulties. We can get lost in them – and it’s important to keep the big ideas close to us.

We want to be able to explain to students why they are learning something and its purpose over all. Students can hold on to these big ideas and how they will be able to use them…much more than each and every standard. We want to bring learning alive.

Assuming we have a broad set of knowledge, skills, and characteristics that we want our graduates to have, let’s take a bit of time to think about the system we want that will support it.

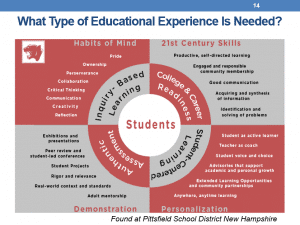

At Pittsfield School District in New Hampshire –

- they want the system to be personalized so that each student gets what he/she needs to be successful

- they want it to be inquiry-based so students are active learners

- they want to make sure students are building habits of mind and twenty-first century skills.

- they want authentic, performance-based assessments to ensure students can apply what they are learning to new situations

The question is, how do we make sure there is an infrastructure that makes sure students are learning?

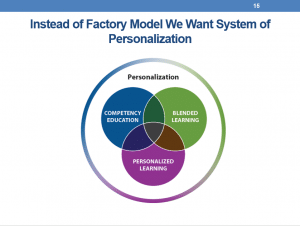

The way we are going to make sure students are college and career ready is through greater personalization – being able to ensure that students receive the learning opportunities, instruction, and support they need to be successful. I use the phrase personalized system in contrast to describing the traditional system as a factory model. Right now, our best thinking to date is that to create a personalized system, we need to have a competency-based structure, a student-centered approach (sometimes referred as personalized learning) that engages and motivates students to have greater ownership over their education, and then the technology to offer more flexibility in pace, place, and path.

The traditional, time-based system was never designed to ensure equity. In fact, it depended on similar curriculum and amounts of instruction to be able to sort students. In comparison, we are re-engineering to create a personalized, competency-based system to make sure every student is learning every step of the way so they are prepared for the next level of study and the next stage of their life.

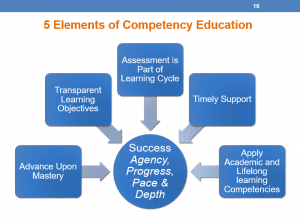

In 2011, 100 innovators in competency education gathered together to create a working definition of competency education. It has five components and ALL FIVE ELEMENTS are NECESSARY.

- Students advance upon demonstrated mastery. This means we need to create the capacity to support students who need more help as well as the ability to let students fly beyond their grade level.

- Explicit, measurable, transferable learning objectives that empower students requires intentionality and transparency. The issue of empowerment or what we often call student agency, voice, and choice is an enormous change. Personalized learning and student agency are two sides of the same coin. In order to run personalized classrooms, students need to take a much higher degree of ownership of their education so teachers are not needed to answer every questions. I have been in classrooms where students are all working on different units. They know exactly what they are working on, how to get help if they get stuck, and what they need to do to demonstrate mastery. It’s all because of transparency, establishing a strong culture of learning with tools and protocols to support student agency, and coaching as students build the habits of learning.

- Assessment is meaningful and a positive learning experience for students. We want students to be able to fully participate in the cycle of learning by receiving timely feedback. If the feedback comes too late or without enough information for a student to address their misconceptions, it is not a positive learning experience. In addition, we challenge the notion that students should take summative exams before they have demonstrated proficiency.

- Students receive timely, differentiated support based on their individual learning needs. This means that students are working in their zone of proximal development and receiving more instructional support when they need it. I think of it as just-in-time support. One of the most basic practices we see is Flex Hour so students can get help every day.

- Learning outcomes emphasize application and creation of knowledge, along with the development of important skills and dispositions. This requires us to think broadly about all the skills students need, including habits of learning, as well as ensure we are creating opportunities for students to apply their skills in new contexts. In other words, we need to have the capacity for project-based or real-world learning and performance-based assessments.

I’d like to address the misconception that competency education is only about pace. The phrase “learning is a constant and time is a variable” has led many to believe that competency-based education is synonymous with online learning. That is wrong. Competency-based education is much more than pace and time – it a structure to ensure that students succeed. Online learning can be incredibly helpful in a competency-based school, but progressing through software or an online curriculum does not necessarily provide transparency, extra support, and opportunities for deeper learning.

In a competency-based district, educators are keeping their eye on depth of learning and pace to make sure students are making progress.

When I’ve visited schools where all five of these elements are in place, I have found motivated students, incredibly engaged educators collaborating on how to improve instruction and their skills, and this phenomenal culture of innovation. Ty Cesene of Bronx Arena said it best: We aren’t going to stop innovating until 100 percent of our students are graduating.

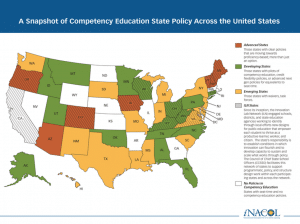

Competency education is spreading across the country. As soon as CompetencyWorks updates this map, we hear of another state taking a step forward. For example, in June, Idaho and Ohio both decided to invest in pilots. However, the thing that convinces me we are going in the right direction is that districts, without the help of any enabling state policy, are converting to competency education – Lindsay in California, Warren and Springdale in Arkansas, Charleston in South Carolina, Henry and Fulton in Georgia, Freeport in Illinois, and Lake County in Florida.

Competency-based education has been developed in rural communities. All of the leading districts are in smaller, rural districts. A few examples are Chugach in Alaska, Lindsay in California, and Sanborn and Pittsfield in NH.

One of the things that is really important to remember about competency education is that it is based on a different set of values and assumptions than the traditional system. I’m sure you’ve seen this drawing:

Who sees the young woman?

Who sees the old woman?

The first time I started using this image, I could not see the old woman for the life of me. The more I see it, the easier it is for me to switch back and forth. But I still have to look for her. That is the power of a paradigm shift – with a different perspective, one sees new opportunities. But we have to train ourselves in the new perspective.

Increasingly districts are approaching competency education as a technical reform, rather than taking the time to understand the shift in the paradigm. I think this is a problem. The new values and assumptions are absolutely essential, otherwise the new competency-based system doesn’t work smoothly.

Here are a few of the new assumptions:

- The traditional system was based on a Fixed Mindset in which we were comfortable that some kids were going to do better in school because of aptitude or income than others. Comptency education starts with a Growth Mindset.

- The traditional system is based on the delivery of curriculum, again with some students learning and others not so much. In competency education, teachers teach children, not a curriculum.

- In traditional system, compliance was the primary value of the adults and the students. In competency education, empowerment is a strong value with educators able to respond to children’s needs and students developing ownership over their education.

Honestly, I’m still trying to fully understand the differences in values and assumptions. It’s most likely that you will feel a bit disoriented as you begin to embrace a new set of values and assumptions. At many districts, it creates an urgency to change because once teachers come to terms with the problems of the traditional system, they can’t tolerate operating in it any more. After a few years, people fully re-orient to the new values and assumptions, although sometimes it is hard to get rid of some of the traditional practices and rituals. When you talk to people at Lindsay and Chugach – they just live and work in a different paradigm. It’s all crystal clear to them.

The discussion these days is very confusing about personalization because two different camps use the same terms – those that emphasize relationship and student voice and those that emphasize technology. And you will notice that I called the system we are building a personalized system, but make a distinction with a personalized approach to learning.

Here is one of the better definitions of personalized learning with what I see as three elements: understanding needs and interests, emphasizing voice, and creating more flexibility.

We still have a ways to go to really understand the implications of student agency, voice, and choice. Student agency is based on having the skills or the habits of learning to manage learning. Voice is expression, contributing, and leadership. Choice is probably the easiest – how am I learning something, and how am I demonstrating that I know it?

We want to design a system that is personalized enough to ensure students are successful, especially those who have been historically underserved – low income, Native American, African American, Latinos, English language learners, and our students with disabilities. We are designing a system in which failure is not an option.

I know that with your ARI, you are well-versed in blended learning. It is an important strategy for increasing flexibility.

Blended learning allows us to draw from the best of what online learning can do and what teachers can do when working directly with students. We know that it creates more choice in the when, where, and how students learn. The power is in how it can allow students to focus exactly where they are on their learning continuum and how it provides more flexibility about the time they need to really learn something.

The one thing we need to be careful about is what adaptive software can and can’t do at this point in time. It obviously can provide much more rapid feedback and assessment than teachers can. However, it is primarily focused on recall and comprehension but not the higher levels of learning. Thus, we need to make sure our teachers are ready to guide students toward the higher levels of learning.

I wish I could describe how we make the conversion from a traditional system to personalized one able to integrate competency education, personalization, and blended learning, but we haven’t had any examples of districts that did all three simultaneously. We are starting to try to figure that out.

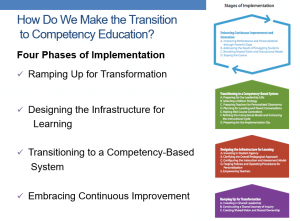

What I can talk about is the process to competency education. CompetencyWorks released a paper this summer on the implementation of competency education. Based on discussion with district and school leaders, we identified four phases: ramping up, designing the infrastructure for learning, the actual transition, and then entering into continuous improvement.

The first phase, Ramping Up for Transformation, is absolutely the most important stage. It is the stage in which the new values and assumptions are developed and educators have a chance to understand the implications. It is the time that districts and schools shift from compliance-oriented strategies to creating empowering organizations that can produce sparkling cultures of learning. It is through developing shared leadership in a shared journey of inquiry that we develop the spirit of competency education – empowerment and a love of learning.

I’ve come to believe that if a district or school skimps on the ramping up process, they won’t be able to sweep away the underlying values of the traditional system or build the new habits that will drive the competency-based system.

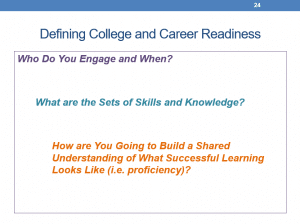

I know I’ve covered so much, so let me sum up by redefining the task at hand – as you go through the process of defining what college and career readiness means think about it in three ways. First, it is a process: Who are you going to engage and when in the process? Second, what types of skills, developmental benchmarks, and knowledge will you include in the definition? Third, what are the implications for operationalizing it so that educators develop a shared understanding of what it means for students to be proficient in those skills and ready to move on to the next step in their learning?

You have already started building so many pieces of the next generation system. The important thing is to keep students smack dab in the center of your design work and strategies. I always know a competency-based school is making the paradigm shift when I see the question What’s Best for Kids? up on the walls in the room where decision-making happens.