Making the Shift: Why Is It So Hard to Scale Equitable, Learner-Centered Education?

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post is the first in a series that previews the ideas, theories, and research in the new report: Teachers Making the Shift to Equitable, Learner-Centered Education: Harnessing Mental Models, Motivations, and Moves.

The Promise

Most educators agree that the traditional “sit and get classroom” will not help us achieve greater educational equity or promote the deeper learning skills our students need to succeed.

In response, a growing number of schools, districts, and states are embracing approaches that are more equitable and learner-centered. These approaches nurture and leverage each student’s unique profile of strengths, needs, interests, goals, family and cultural background, and experiences to enable them to succeed. Learning science research suggests that these approaches are well aligned with how humans learn. The trend towards more equitable, learner-centered education is showing promise for reducing educational disparities and promoting deeper learning outcomes for all students.

So, why is it so darn hard to scale equitable, learner-centered education?

The Problem

Despite the promise of equitable, learner-centered education and the growing momentum for this approach, many districts and schools remain stuck in the pilot phase. In particular, educational leaders, professional learning designers, and facilitators are finding that it can be hard to expand equitable, learner-centered practices beyond those pioneer teachers who may have already been receptive to these ideas from the start. There are three reasons the field may be facing this problem.

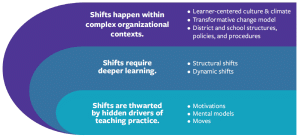

Three Challenges With Scaling Equitable, Learner-Centered Practice Shifts

1. Shifts happen within complex organizational contexts.

First, teachers do not operate in isolation—but rather within complex and dynamic organizational contexts. In order to bring about substantive and lasting change, districts and schools need:

- a foundational learner-centered culture and climate that can support and sustain shifts in teaching and learning;

- a transformative change-management approach that enables teachers to engage in complex organizational change; and

- a set of structures, policies, and procedures that reflect the organization’s equitable, learner-centered goals to give teachers and school communities the cultural and foundational tools they need to collectively implement this approach.

2. Shifts require deeper learning.

Second, an equitable, learner-centered approach is a set of complex and sophisticated skills that can be challenging for teachers to learn. Unlike other educational reforms that might require following a new curriculum or adopting new technology tools, those teachers interested in adopting an equitable, learner-centered approach must become skilled, creative, and adaptive designers, facilitators, and assessors of human learning. This necessitates dramatic and fundamental shifts in both the structural and the dynamic aspects of their teaching practice as they develop critical consciousness and a new area of expertise.

Unpacking these shifts and guiding teachers in knowing how to navigate this more complex and nuanced approach to teaching and learning is nothing short of daunting—and will require them to engage in their own deeper learning. This is a heavy lift even for those teachers who are already excited about, and receptive to, making the change.

3. Shifts are thwarted by hidden drivers of teaching practice. This means change is much harder than we think!

Third, shifting teachers’ daily practice is a lot harder than we think. Seasoned teachers are already the masters of their own well-established classroom practice. Their existing practices have been thoughtfully constructed, honed, and reinforced over many years. We know from the learning sciences that changing the thinking, beliefs, and behavior of experienced professionals is not easy or straightforward. That is because skilled performance is driven in large part by a set of hidden emotional, behavioral, and motivational factors that influence daily decisions and actions.

Implications of the Hidden Drivers of Teacher Practice

How can designers of professional learning address these hidden drivers of teacher practice?

Teachers cannot simply learn new ways of doing things, they must also “unlearn” their old way of doing things.

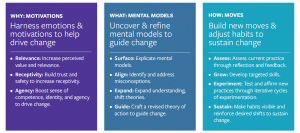

We know from the science of human learning that bringing about deeper learning and the accompanying substantive shifts in existing practice will necessitate addressing three learning networks—the what, the why, and the how.

For teachers, this means addressing needed changes in their:

- emotional responses and motivation to change;

- implicit biases and mental models of teaching and learning; and

- ingrained teaching habits that help or hinder the adoption of new moves.

Shifting Teacher Practice by Addressing Motivations, Mental Models, & Moves

The tricky part is that for experienced professionals enacting their craft, all three of these networks typically operate primarily outside of their conscious awareness, and are, therefore, particularly difficult to change.

Unless we confront these hidden drivers, we will continue to fall short in our efforts to scale equitable, learner-centered approaches.

The Opportunity: Leveraging the Learning Sciences to Tackle Three Hidden Drivers Thwarting Change Efforts

Luckily, we can build upon the principles of equitable, learner-centered practices and draw on the learning sciences to create a new frame for how we design teacher learning experiences to explicitly address these hidden factors that drive their practice, including:

- embracing and harnessing teachers’ emotional responses to change to help them become more authentically motivated (rather than coerced) to change;

- uncovering and refining teachers’ mental models (i.e., underlying theories, implicit biases, and assumptions about their students and about teaching and learning);

- helping teachers translate their new pedagogical beliefs into their everyday classroom moves by identifying and weakening undesirable habits and helping teachers construct new ones.

Addressing teachers’ mental models, motivations, and moves may not be the one silver bullet we need to scale more equitable, learner-centered education. However, explicitly addressing these three hidden drivers of teacher practice throughout professional learning will bring about more substantive changes, more effectively, and more efficiently than our current efforts alone.

We know from the science of human learning that bringing about deeper learning and the accompanying substantive shifts in existing practice will necessitate addressing three learning networks—the what, the why, and the how.

Ready to get started?

Check out our other posts in the Making the Shift blog series, as well as the professional learning exercises designed to address the hidden drivers of teaching practice that can thwart change efforts!

- Caution: Change Ahead! How Harnessing Emotions and Motivations Can Help Drive Change for Equitable, Learner-Centered Education

- Sabotage! How Our Implicit Biases and Mental Models Keep Us From “Walking the Talk”

- Old Habits Die Hard: How to Build New Moves and Habits to Sustain Change

- Professional Learning Exercises for Teachers Making the Shift to Equitable, Learner-Centered Education

Dig deeper into the theory and research underlying an equitable, learner-centered approach in the Making the Shift report or watch this webinar with report authors and practitioners Dr. Patrick Hardy and Chanda Hassett, in which they discuss the report and what making the shift can look like in practice.

Wendy B. Surr is a senior research consultant and project director with more than 30 years of experience leading research and evaluation studies, state and local education initiatives, and technical assistance services. Surr specializes in the development of assessment systems designed to measure learner-centered teacher practices and associated student deeper learning outcomes. As a Senior Researcher at the American Institutes for Research (AIR) for seven years, Surr conducted numerous research studies examining learner-centered, competency-based, and deeper learning practices and led the study Learning with Others, which examined the role of collaboration in enhancing outcomes for students of varying racial and ethnic backgrounds. In the past three decades, Surr has led numerous technical assistance projects, including: partnering with the Illinois State Board of Education to launch a statewide competency-based learning initiative with over 45 districts, serving as lead for the Regional Deeper Learning Initiative, which helped the states of Ohio, Illinois, Indiana and Iowa to advance deeper learning and competency-based education practices; and developed and launched CBE 360, a multi-state professional learning initiative focused on the dissemination of a comprehensive toolkit designed to support implementation of CBE practices by districts, schools, and classroom educators. Surr holds a B.A. in Psychology from Bard College and an M.A. in Early Childhood from Tufts University.