Five Quick Thoughts About Accountability

CompetencyWorks Blog

There is a flurry of conversations about federal accountability policy and assessment going on around the country. You may have heard about it described as accountability 3.0. I had the opportunity to participate in one of the conversations last week and just finished listening to the conversation led by Maria Worthen, iNACOL and Lillian Pace, KnowledgeWorks held today based on their report A K-12 Federal Policy Framework for Competency Education: Building Capacity for Systems Change. And I’m feeling inspired to jot down a couple of my thoughts:

There is a flurry of conversations about federal accountability policy and assessment going on around the country. You may have heard about it described as accountability 3.0. I had the opportunity to participate in one of the conversations last week and just finished listening to the conversation led by Maria Worthen, iNACOL and Lillian Pace, KnowledgeWorks held today based on their report A K-12 Federal Policy Framework for Competency Education: Building Capacity for Systems Change. And I’m feeling inspired to jot down a couple of my thoughts:

1. Federal policy must NOT mandate competency education. We want it to enable competency education and eliminate any elements that inhibit it. Federal policy can even catalyze it. But at this point in time, federal policy should not expect everyone to do it. There are several reasons for this. First, any top down, bureaucratic approaches are just inconsistent with the student-centered, do what it takes, spirit of continuous improvement that is essential to personalized, competency-based schools. Second, we don’t have enough research and evaluation to tell us about quality implementation or what we need to ensure that special populations and struggling students benefit. We just aren’t ready yet.

2. Assessment comes before accountability. It’s almost impossible to untangle accountability from assessment in today’s policy context. That’s because the accountability system has required states to have a specific type of assessment system. This is a huge problem because assessment should be focused on helping students to learn. Instead we see it as part of the accountability system. I know this is too simple… and all the accountability and assessment experts out there might dismiss this. But I just don’t think we can go where we want to go if we start with the requirements of today’s accountability system driving learning. So I think we need to define what is really important for systems of assessments and then draw from that what might be valuable for any type of accountability system. Let’s keep our priorities straight by focusing on assessment and accountability not accountability and assessment.

3. Challenge ourselves to develop an accountability policy that has one set of reporting systems. Valerie Greenhill, EdLeader 21 raised the point in a meeting that the districts that are dedicated to continuous improvement keep two sets of reporting systems. One helps them improve their schools and respond to students. The other is designed to meet the information requirements of state and federal accountability requirements. That suggests to me that our current accountability system isn’t helping schools improve. As we think about redesigning accountability, let’s see if we can create policies that are fully aligned with continuous improvement so that districts can keep one set of books. It’s a good way to test whether our ideas are viable.

4. Accountability policy has to take into consideration 21st century skills or CCR skills as well as academic content and skills. Our federal policy is now all about college and career readiness (CCR). If we want districts and schools to be preparing kids to really have that set of skills to manage their own learning, apply learning in new and complex situations, and help to solve problems in collaborative settings (i.e. deeper learning), it’s going to be important for federal accountability policy to really value them. How ready are we to do that? I’m not sure…. I’m still trying to work through the materials from a meeting that Center for Assessment held on assessing college and career readiness.

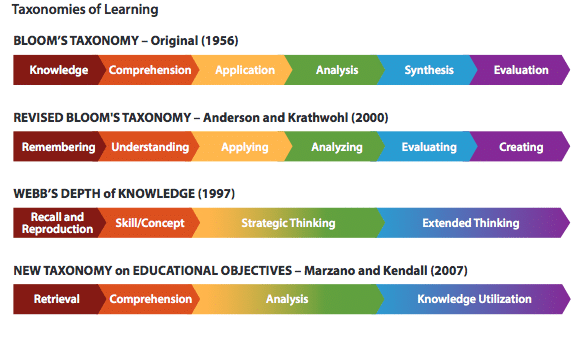

5. Is it possible to balance student-centeredness with the desire to create high leverage policies that emphasize systemic reform? There are a number of issues that start to pop up once students begin to have agency. For example, how do we compare students that want to zip through the math competencies (think Common Core State Standards) at Level 3 (Analysis) compared to another who wants to go slower but with lots of time to explore at Level 4 (Knowledge Utilization). Take this same comparison, but now think about students who enter school at a significantly lower level on the learning progression, perhaps a sixth-grade student who is a refugee from a war-torn country that has had little formal education. Do we expect that student to catch up (i.e. learn faster than we expect other students who have been consistently in school)? Or is gaining one year of academic growth acceptable even if they are always “behind”? Do we know enough about what it takes to accelerate learning to expect schools to do it? I’m a full supporter of the idea of accelerated learning, but I haven’t been able to find compelling research that really informs us how to do it and how to think about the most cost-effective methods.

It’s going to get even more complicated when we get to high school. Are we going to stand firm that students that do not demonstrate proficiency for all of the Common Core standards should not get a high school diploma, so that we make sure that the diploma is meaningful and the system continues to have pressure to improve? What if they demonstrated proficiency in all of math standards but not ELA? Still no diploma? Are we committing the student to a lifetime of poverty as a consequence? This kind of thinking puts the system before the student, long-run benefits over the well-being of students in the short-run.

Or is there another way? Perhaps we can create diplomas that tell us what students have learned, providing options for how they can keep learning, and provide multiple ways for students to demonstrate that they are ready for the transition to their next stage of work and learning. That also provides feedback to the system so that schools know how they can improve and as a nation we can monitor how we are doing in improving the system. Can we create diplomas that are meaningful to ongoing learning rather than as an endpoint? I know this idea is half-baked…. I just have to believe that there is a way to hold schools accountable that doesn’t also shut the door to students who have been playing by the rules, trying to learn, but haven’t met every expectation that state legislatures and schools boards set for graduation.

—

I certainly don’t know the answers to any of this. What I do know is that if we are going to expect our schools to be student-centered, we need to create room in our policies to allow them the flexibility to do so.