How Will Your Research Narrate Our History?

CompetencyWorks Blog

Jilliam Joe, Senior Director of Learning Insights and Research at LEAP Innovations, delivered the keynote address at the Aurora Institute’s recent National Research Convening on Building the Evidence Base for K-12 Personalized Learning.

Jilliam Joe, Senior Director of Learning Insights and Research at LEAP Innovations, delivered the keynote address at the Aurora Institute’s recent National Research Convening on Building the Evidence Base for K-12 Personalized Learning.

Hello! I’m honored to be here with you today. Many thanks to the Aurora Institute for organizing the meeting and inviting me, and to the Leon Lowenstein Foundation for sponsoring this meeting. It is so necessary for us to gather together and collaborate and build community in this space.

These last seven months have tested us on every front. They have tested the quality of our health, our economy, our humanity, and our hope. However, I’m encouraged by the resilience, determination, and compassion of the human spirit displayed through those who are working on the front lines of this pandemic, those who continue to march physically, intellectually, and politically for racial justice and anti-racism, and through our students, families, and educators who are making the best of remote and blended learning. I know some of you are supporting your own children in remote learning at the same time that you’re participating in this convening today. So thank you so much—thank you for everything you do!

I’ve spent close to twenty years of my professional life serving educators and students; first, as a researcher for Norfolk State University’s Office of Institutional Effectiveness and Assessment; then at Educational Testing Service where I focused on the measurement challenges related to performance-based assessments, particularly in the teaching effectiveness space; then as an independent consultant to Ohio’s resident educator summative assessment; and currently as the senior director of research for LEAP Innovations, a Chicago-based non-profit. Fundamentally, I’ve devoted my career to understanding and working to mitigate the factors that influence the quality of educational assessments when they are used as opportunity and career gatekeepers.

Now, I have to be very honest with you. I’m coming to this space today bearing the weight of my professional identity and the complexities of my identity as a Black woman who has spent more time in spaces that were not designed for me—or with me in mind—than in those that were. In other words, I’m bringing my history with me today, as are you. Perhaps like many of you, I’m also grappling with how to leverage all of who I am in helping the K-12 education field advance and serve young people in more equitable and inclusive ways over the next five to ten years.

I’d like to pause for a moment and take a poll of the audience. During your research and quantitative methods courses, how many of you were prompted to reflect on how your identity and privilege influenced your research practices? I want you to type “yes” in the chat box if that was true of you. [Responses were 21% yes, 79% no.]

There we go. That’s what I thought! Thank you all for your honesty. Well, I had the great fortune of getting some of that in my qualitative courses, but, like you, not so much in my quantitative research methods courses. During my doctoral program, I learned how to account for race in my research and we examined interesting “problems” like stereotype threat and test-taker motivation among African-Americans as ways to explain differences, or “gaps,” among test-taker performance. But as the only Black student in my cohort, I cannot recall engaging with my all-White faculty and peers in authentic conversations about Whiteness, privilege, and power and how they influence Black and Brown students’ learning and testing experiences. In looking back on that time, I see it as a critical missed opportunity in the education of researchers who would go on to influence education policy and practice.

Arguably, there isn’t a more opportune time than now to study personalized learning and to have the hard but necessary conversations about its intersection with racism, class, and systemic differences in America’s classrooms. One of the key questions that we are tasked with answering as we build the evidence base for personalized learning is, “Does the practice help to create more equitable and inclusive environments that honors every child’s identity and bolsters their social and cognitive development? Moreover, do these practices help to close the opportunity gap between White, Black, and Brown children?”

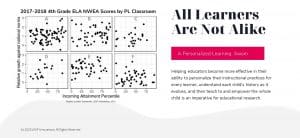

Personalized learning provides us with a useful philosophical framework for approaching research on personalized learning—research that has gone through an equity and inclusion lens. One of the tenets of personalized learning is that every learner is unique in their academic and social and emotional needs, interests, and strengths. We see evidence of this variability within and across classrooms in a school. [The slide below] shows you six classrooms in one school that’s practicing personalized learning. And there’s variability in both incoming academic performance and end-of-year growth. And so I believe that it is imperative for us as researchers to support educators in personalizing practices across 25-plus students in a classroom who have such a diversity of strengths and interests and needs.

If we are to use personalized learning as a philosophical framework for our research, then we have to probe the empirical space for cases where personalized learning works, and also for cases where the theoretical model doesn’t fit, or cases that defy the theoretical model—so really probing the edges of personalized learning. So the questions are, “For whom does personalized learning not work?” and “For whom does personalized work, and why?” It’s always the “why” question that we have to continue to pursue in our research efforts. If we ignore or omit these cases or transform our data in such a way as to make these cases common with the rest of our data set, then we run the risk of painting an inauthentic narrative about personalized learning. And I know that none of us do this [laughs]—none of us drop outliers—but it has been done, and it’s inauthentic as we are building the evidence base not to understand who those outliers are and what they represent in terms of context and experience—their history.

LEAP brought together a panel of researchers and practitioners from institutions and organizations across the nation to review the LEAP Learning Framework. During one of the whole-group discussions, the subject of agency and culture came up. Several of the panelists pressed us to consider how our Western orientation of agency might play out in communities where children are not encouraged to be heard or make the physical space serve them. Up until that point, I never imagined the conflict that a child might experience to be empowered in one space and diminished in another. Conversations like the one we had that day continue to challenge my assumptions about how I expect children and adults will show up in the research that I lead.

If we aren’t careful to monitor and challenge those assumptions that we oftentimes bring to this space, no matter how objective or impartial we try to be, we run the risk of creating a narrative that reinforces stereotypical beliefs about who can and cannot own their learning. I suppose what I’m advocating for is a more holistic approach to our research that integrates the “what” and the “why”—the quantitative and qualitative inputs.

At LEAP, we collaborated with our research advisory board to sketch a potential pathway for the next five years of our research. The pathway advances from exploratory and descriptive research to more rigorous hypothesis testing. You’ll notice that across each of the three stages [in the slide below] there is the integration of empirical research with “life” stories. Later this afternoon, my colleague Emily Bader will share with you how we have used “life” or impact stories to help illustrate the evidence of change in our schools more vividly.

Because we are a non-profit and are accountable to our funders to provide evidence of impact, we’ve spent most of our time and energy in our research in Stage 3, examining the causal relationship between our intervention on educator’s teaching practices, their implementation of personalized learning in the classroom, and student academic outcomes in ELA and math. After six years, we have promising evidence that personalized instruction is helping students achieve their goals and meet grade-level standards. What we have seen most consistently through our programs is that teachers are making the shift from teacher-centered pedagogy—what we might define as “traditional” teaching—where instruction is directed by and owned by the teacher, to more learner-centered practices, where you start to see more collaboration between teacher and students, even within the lower grades. (Yes, the kindergarteners can do it too.)

Teachers who engage in this work have observed statistically and practically significant gains in their students’ literacy and math skills—gains that surpass their student peers. In the second cohort of LEAP’s Elevate program, which combines learner-centered instruction and ed tech with a plan for whole-school redesign, students in the program showed gains of 7 percentile points in literacy and 12.5 percentile points in math, as measured by NWEA, relative to a comparable control group. For the fourth cohort of our 18-month program, we saw an impact on truancy behavior in middle school students. For the sample of students in the study, learner-centered instruction reduced the likelihood of an unexcused absence by 48%, relative to their peers! I am pretty proud of the work that our team of professional learning experts and educators and students have done in these classrooms across the last six or so years. Really incredible work. And so now we have to tell the story.

We are in a unique situation with the pandemic, where there’s a dearth of the student outcome data that we expected to have this year, and that gives us the opportunity to focus more on Stage 1 research. What we have proposed to do, along with other organizations including NGLC, and hopefully we’ll be able to kick off a larger project, but LEAP is executing a research project focused on deconstructing the deficit narrative that has shrouded African-American school communities, particularly with respect to the success, or lack thereof, of remote learning. What we want to be able to do is probe our exemplar schools—the schools that we have worked with that have gone deep in personalized learning—and elevate the innovation and the work that teachers, school leaders, students, and their family members and networks are doing to buoy students and to ensure that this year is as successful as possible for these students.

We don’t want to paint an all-rosy picture, because we know it’s not all rosy, and we know there are still needs and gaps in this space, but what we want to able to do through this largely qualitative study is to paint a more comprehensive picture of what is happening in remote learning and the role that personalized learning is playing in it.

So here’s our call to action as researchers. We have to aim to be seen as authentically adding to our storehouse of knowledge and perception about every child’s ability and potential in this space. And what we have to do is not only honor the history that our school communities are bringing to the research space, but we have to honor our own history and interrogate what we are bringing to the space.

[The slide below shows] how we do that. First, we interrogate our beliefs, assumptions, and biases. I think that we have to engage in critical conversations about racism, diversity, equity, and inclusion as a research community—we can’t just observe it, because we are part of it, so we have to talk about it, especially in this personalized learning space where there’s so much potential to up-end historical, systemic issues in our schools that have created these gaps in academic performance across racial and ethnic groups.

We have to reject deficit mindsets about the communities we’re studying. It’s important for us to probe “What is the mindset I’m bringing to this research space about this community?” We have to acknowledge our position of power and privilege, and work collaboratively and share power with the communities we are studying. As I said earlier, personalized learning is the perfect philosophical framework for the work we do. How are we allowing the community that we’re studying to lead us to their truth? How are we sharing power with these communities in our research? How are we working collaboratively with them? So the same things that our professional learning communities are doing in the classroom, we have to adopt as researchers.

And finally, we have to commit to telling their story with empathy. Especially this year. I think that as researchers we have the opportunity to be great storytellers this year. Of course not diminishing the rigor or the scientific nature of our work, but working very hard to allow the voice of our community and students and parents and teachers to really speak authentically to the phenomena or the challenges that they are facing.

That’s it! Thank you so much for all the work that you all are doing this year. I’m so excited to hear more about how everyone is pivoting, what evidence you all have found in this space, and I’m really grateful to lock arms with you in this work. Thank you again to the Aurora Institute for inviting me, and I’m looking forward the rest of the day.

Learn More

Learn More

- How Will Your Research Narrate Our History? – Video of this keynote address.

- Equity-Based Educational Research: Emerging Lessons from City Year’s Work

- A National Landscape Scan of Personalized Learning in K-12 Education in the United States

Jilliam Joe, Ph.D., is Senior Director of Learning Insights and Research at LEAP Innovations. At LEAP, she leads program evaluation and development of measures of personalized learning and instructional practice. She co-authored Better Feedback for Better Teaching: A Practical Guide for Improving Classroom Observations.