Essential Components of Local Assessment Systems for Personalized, Proficiency-Based Learning

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the first post in a series by Pat Fitzsimmons, Team Leader of Proficiency-Based Learning at the Vermont Agency of Education. Links to the other posts are at the end of this article.

Local Comprehensive Assessment Systems (LCAS) are essential for ensuring equitable learning opportunities for all students. They have the potential to ensure that each and every learner meets high expectations that are set across all content areas. Since LCAS is one of four levers highlighted by the Vermont Agency of Education for supporting the success of all students, the agency held convenings with educational leaders to refine tools and investigate resources that can improve local systems that support personalized, proficiency-based learning.

This is the first of four blog posts in which I’ll describe these convenings. The posts focus on rationale and essential components, formative and summative performance assessments, and student-designed performance assessments.

Engaging Assessments

“What is the most interesting way that you have ever demonstrated your learning?” That question was posed to educators at the beginning of our first Local Comprehensive Assessment Convening. Responses ranged from operating a forklift to riding in a horse show. They demonstrated that the “way you show that you have learned something,” or assessment, can be engaging, relevant to the learner, and provide opportunities for continued growth. How do these compare to assessments that are typically part of our educational systems?

To get a better understanding of what is currently happening in schools, teams of educators were asked to draw a diagram representing the current state of their assessment system. Many included the screening, diagnostic, and monitoring assessments that are used to determine who is on track for meeting grade-level expectations in mathematics and English language arts and who needs additional support. These assessments are certainly an important component. However, what about:

- Assessments that require students to actively demonstrate their proficiency in diverse and interesting ways like the forklift and horse examples that teachers shared at the start of our convening?

- Assessments that are meaningful and engaging for learners?

- Assessments that measure transferable skills essential for succeeding in the 21st Century?

Where do these types of assessments fit into an assessment system?

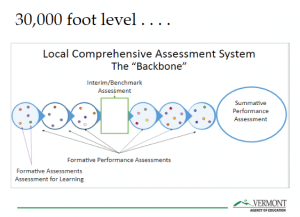

Local Comprehensive Assessment Systems: The “Backbone”

Let’s start at the “30,000-foot level” and work backwards.

Chris Jernstedt, Professor Emeritus of Psychological and Brain Science at Dartmouth, provided workshops about the brain and learning for educators throughout Vermont. Numerous times he commented, “The person who is doing the work is doing the learning.” If that thinking is applied to educational systems, then students should be actively engaged in “doing the work.” Essentially, the process of “doing the work” should provide opportunities for students to demonstrate what they have learned.

Chris Jernstedt, Professor Emeritus of Psychological and Brain Science at Dartmouth, provided workshops about the brain and learning for educators throughout Vermont. Numerous times he commented, “The person who is doing the work is doing the learning.” If that thinking is applied to educational systems, then students should be actively engaged in “doing the work.” Essentially, the process of “doing the work” should provide opportunities for students to demonstrate what they have learned.

Formative performance assessments provide that opportunity. They require students to apply learning, or perform, in order to demonstrate their current level of understanding. Educators and students can then use the information that is generated to determine next steps for the learner. The second post in this series provides examples of specific formative performance assessments used in classrooms.

Formative assessments embedded within performance assessments allow teachers and students to continually check performance levels related to identified goals and make adjustments as needed to instruction and learning opportunities. An interim or benchmark assessment provides a “dipstick” that answers the questions:

- Are students where they need to be at this point?

- What do they understand?

- Where are they confused?

- Who is ready to move on?

- Who needs additional support?

Finally, summative or comprehensive performance assessments allow students to pull together multiple pieces of information to demonstrate their learning in a new context. Learners demonstrate their level of knowledge, understanding, and skills to produce a product and/or performance that serves as evidence of learning.

The complexity of performance assessments allows each learner an entry point. Some may demonstrate proficiency upon completion of the task, while others will need additional opportunities. This reflects the kinds of “assessments” that are faced on a regular basis in the workplace as well as those that our convening participants originally described as most interesting.

Linda Darling-Hammond and her colleagues (2013) suggest that a high-quality assessment system should include assessments of higher-order cognitive skills as well as critical abilities such as communication, collaboration, modeling, problem solving, reflection, and research. These assessments should be valid, reliable, fair, and have value for informing teaching. They should also be instructionally sensitive—i.e., representative of content and concepts that students learned from curriculum and instruction.

Assessment Systems: A Closer Look

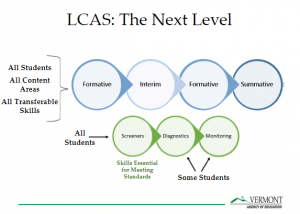

What you do not see in the “big picture” diagram above of an assessment system, however, are those finer-grained assessments—screeners, diagnostics, and monitoring—that are also essential components of this system. The Vermont Multi-Tiered System of Supports Field Guide states: A balanced system recognizes that no single assessment can capture all important aspects of standards and curriculum, nor important outcomes in every domain. Multiple, varied and recurring assessments are needed for that.

Screeners, typically related to mathematics and English language arts, are administered to all students in an effort to predict who may have learning challenges. Diagnostics, more in-depth assessments of essential skills, can then provide additional information so appropriate supports can be provided. Finally, monitoring is essential to ensure that learners are making progress. The goal, therefore, of a strong assessment system is to intentionally gather information that provides an accurate picture of each learner—their strengths and areas in need of support—in order to enable them to succeed.

A Self-Assessment Tool: Quality Criteria for Local Comprehensive Assessment Systems

A Self-Assessment Tool: Quality Criteria for Local Comprehensive Assessment Systems

After clarifying the big picture, participants had the opportunity to reflect on their own assessment systems using the Quality Criteria for Local Comprehensive Assessment Systems. This document is intentionally posted as a word document so educational leaders can tailor it to meet their needs. Some of the essential components include:

- The assessment system has a theory of action aligned to the Continuous Improvement Plan that states how assessments are connected to intended outcomes as well as how the parts of the system are related.

- Assessments provide equitable access for students with diverse needs and backgrounds.

- Assessments are aligned to clearly described standards/proficiencies for all content areas and transferable skills.

- Assessments are aligned PreK-12 and across classrooms within a grade level to support learning and avoid unnecessary duplication.

- Multiple measures including universal screeners, diagnostics, progress monitoring, formative and summative assessments, performance assessments, and state assessments comprise a comprehensive assessment system.

Root Cause Analysis: What are the challenges?

Finally a fishbone diagram was used to uncover challenges connected to constructing strong assessment systems. The capacity to collaborate, create assessments, and calibrate scoring, especially in small schools, was raised as an issue. Data analysis tools and resources, along with assessment literacy, were also identified as areas in need of support. The data from these diagrams, as well as information gleaned from rich discussions throughout the day, will guide future decisions regarding professional learning opportunities that the Vermont Agency of Education will provide.

In the subsequent blog posts we will dive deeper into performance assessments—the backbone of a strong assessment system.

Reference: Darling-Hammond, L., Herman, J., Pellegrino, J., et al. (2013). Criteria for high-quality assessment. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

Note: These convenings are the result of a collaborative effort among colleagues, Maggie Carrera-Bly, Sigrid Olson, Ryan Parkman, Emily Leute, and Pat Fitzsimmons, in the Student Pathways Division at the Vermont Agency of Education.

Learn More

- Improving Student-Centered Assessment Systems With Formative and Summative Performance Assessments

- Student-Designed Performance Assessments for Personalized Learning and Student Agency

- Supporting the Development of Student-Designed Performance Assessments

Pat Fitzsimmons is Proficiency-Based Learning Team Leader at the Vermont Agency of Education. She collaborates with educators to implement proficiency-based learning and assessment systems that are student-centered. She has worked with various stakeholders to construct a Vermont Portrait of a Graduate and co-authored numerous documents related to proficiency-based learning. Before moving to state-level work, Pat was the Science Specialist for the Barre Supervisory Union in Vermont. She also fondly remembers her first fourteen years in public school as a kindergarten teacher. Pat was the first kindergarten teacher in Vermont to receive the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science Education.

Pat Fitzsimmons is Proficiency-Based Learning Team Leader at the Vermont Agency of Education. She collaborates with educators to implement proficiency-based learning and assessment systems that are student-centered. She has worked with various stakeholders to construct a Vermont Portrait of a Graduate and co-authored numerous documents related to proficiency-based learning. Before moving to state-level work, Pat was the Science Specialist for the Barre Supervisory Union in Vermont. She also fondly remembers her first fourteen years in public school as a kindergarten teacher. Pat was the first kindergarten teacher in Vermont to receive the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science Education.