Springpoint’s Phased Approach to Implementing Competency-Based Education, Phase One: Establishing a Solid Foundation

CompetencyWorks Blog

Competency-based education (CBE), also known as mastery-based education, has the potential to improve teaching and learning, empower students to own their learning, and help them develop skills and knowledge that help them succeed. But CBE is challenging and complex for practitioners to implement. It requires a rethinking of fundamental components and practices of school, the skills and mindsets to strategically steward a comprehensive and collaborative rollout, thoughtful communication and partnership with stakeholders, and much more. These aspects of CBE are even more challenging amid remote learning prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic and especially important in getting students engaged in the learning process.

Competency-based education (CBE), also known as mastery-based education, has the potential to improve teaching and learning, empower students to own their learning, and help them develop skills and knowledge that help them succeed. But CBE is challenging and complex for practitioners to implement. It requires a rethinking of fundamental components and practices of school, the skills and mindsets to strategically steward a comprehensive and collaborative rollout, thoughtful communication and partnership with stakeholders, and much more. These aspects of CBE are even more challenging amid remote learning prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic and especially important in getting students engaged in the learning process.

At Springpoint, we partner with districts, networks, and schools to support the design and implementation of new high school models. In working with many of our partners to support CBE rollout—and in our national work visiting and partnering with dozens of schools—we’ve seen practitioners jump into later stages of implementation without first ensuring the core building blocks of a mastery model are solid. When strategically and intentionally implemented, CBE becomes a vehicle for transparency—students own their learning and practitioners are crystal clear about what students need to do to master competencies and what mastery actually entails. This is doubly crucial given what we have seen and heard from schools nationally implementing CBE: that full-fledged implementation takes at least three to five years and requires intentionality, support, and a series of small wins that build over time.

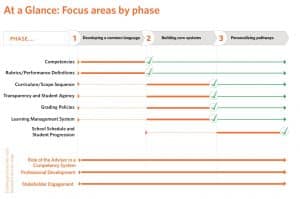

To support our partners in taking a methodical approach to CBE, we suggest breaking down implementation into three phases. We developed a resource that outlines the three sequential phases of CBE and guides schools as they embark on this exciting journey. Take a look at the snapshot below for an overview.

We are sharing this resource, along with this new series of blog posts that describe each phase, to support others who may have similar questions or challenges around phasing in CBE. In this first post in the series, which covers phase one, we discuss the importance and the key steps of developing a common language to underpin CBE systems and practices.

Our guidance for the first phase focuses on developing a common language to underpin CBE. A common language promotes transparency and helps everyone in a school community share a clear understanding of CBE. We will provide some examples of common language and shared competencies in the coming sections. Essential elements of a shared competency language include:

- Using the same competencies across disciplines.

- Ensuring each competency has a standard meaning in all classrooms .

- Shared benchmarks for student work.

- Codifying observable indicators for each competency.

- Ensuring that common language shows up visibly and frequently in the school environment.

- Instituting structures and systems that give teachers space to norm and calibrate around competencies and rubrics.

This consistency not only strengthens a school’s CBE system as a whole but also creates transparency by allowing students to easily understand and access individual competencies and standards in any class and on any project. CBE becomes second nature in a school when everyone is on the same page and shares a commitment to having students become independent learners.

These are the essential tools that ensure everyone in a school internalizes the common language of CBE. In supporting our partners, we encourage them to aim to answer the following questions in phase one:

- What are the prioritized competencies and sub-skills that students need to master in preparation for post-secondary opportunities?

- For each of these, what does mastery truly mean to our school community? How do we ensure this is clear to all, especially students (through shared rubric language, exemplar student work, etc.)?

- What are the essential design components of a learning experience, and how do we create strong alignment to the competencies through them?

- What are the practices that we need to build around delivering clear, consistent, and actionable student feedback?

Two critical practices during this phase center on selecting and socializing competencies and developing a shared vision of mastery through initial rubrics, performance levels, and a bank of exemplar student work. Read on for examples of each of these materials.

Developing Competencies and Defining Performance Levels

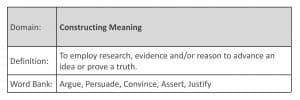

At the start of phase one, we encourage partners to prioritize a set of three to five competencies and accompanying definitions that are shared with staff, students, parents, and possibly community members—along with rationale for how they were selected. Though the number of competencies will likely expand as implementation progresses, we strongly encourage partners to resist the urge to introduce too many competencies in this phase and to be strategic about the kinds of competencies selected. For example, to support our work with partners, we developed a sampling of competency domains and encourage schools to select one from each category.

Sample Competency Domain

When it comes to developing competencies in phase one, we recommend that schools:

- Choose competencies based on a deep understanding of the most foundational requirements of college, career and lifelong learning in the 21st century.

- Find the right “grain size” to ensure competencies are transferable to increasingly rigorous settings over time as well as across a variety of disciplines and in multi-disciplinary contexts.

- Define competencies using teacher, student, and family-friendly language that is shared across all courses and at every level.

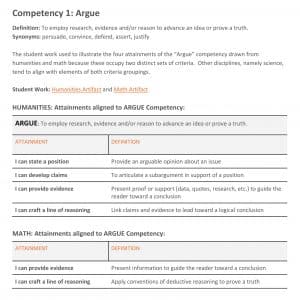

- Include “I Can” statements (also called attainments) to articulate how students demonstrate mastery of each competency.

- For each competency, develop a simple rubric to get as concrete and transparent as possible about the different performance levels. (Springpoint developed a set of examples to demonstrate at a high level what competencies and performance levels can look like: see “Argue”, “Communicate”, and “Discern”).

- Leverage student work examples to provide clarity for teachers and students about what a particular competency looks like at various levels (e.g., exceeding, meeting, and approaching).

- Source inspiration from schools successfully implementing CBE for guidance—instead of reinventing the wheel.

It is worth noting that in this phase, grading policies are not impacted, but grading practices are. The grading rubric is based on the rubric for school-wide competencies and it outlines each performance level, most commonly defined as “approaching,” “meeting,” or “exceeding” mastery. Typically, there is an agreed-upon method for translating rubric ratings to the traditional numerical system (e.g., “approaching” = 70%) if a school needs to report traditional grades. In phase two, the specifics of the school’s grading policies will take shape.

As implementation progresses, each department in the school will eventually engage in a dialogue about what mastery looks like specific to each subject area, and the school community may decide to draft modified rubrics for each content area. But we encourage partners to keep it simple and ensure alignment and a common language before building out the subject-level rubrics.

Finally, it’s important to build in opportunities for stakeholders to ask questions and provide feedback on the competencies and implementation. Collecting ongoing feedback will help hone the language of competencies and sub-skills with scheduled opportunities to make and roll out shifts. One to two times per year is often a comfortable frequency to make changes; this gives students and teachers an opportunity to internalize and work with competencies without needing to change course too often.

School-based Snapshot

In February 2020, we brought our school-based partners to The Young Women’s Leadership School in New York City. We observed classrooms and heard about CBE from students and teachers. But more specifically, we sought to deeply study and understand the impact of common language on student learning at TYWLS. The CBE design at the school has been implemented for over ten years and they utilize the same ten competencies across all content areas. Two specific touchpoints we highlighted that support this work are TYWLS’s ‘Looking At Student Work’ protocol and teacher-student conferencing.

We observed a ‘Looking At Student Work’ meeting where three educators normed and calibrated around high expectations for student work. We also saw a teacher-student conference in which a teacher, Greg Zimdahl, coached an 11th-grade student to self-reflect on a piece of their own writing to identify how she could work toward key competencies. You can see several videos that capture these meetings, as well as more information about TYWLS’s work, here.

Go Slow To Go Fast

While we understand that many practitioners are driven by an acute sense of urgency to roll out CBE to best serve their students, we strongly advise a deeply intentional approach to implementation that does not skip any critical steps. CBE presents a unique opportunity to transform a learning ecosystem. However, when it is not done systematically and with intentionality there is significant likelihood for stakeholders to resist change and an understandable desire to return to more familiar practices. A phased approach to CBE implementation helps build a solid foundation and ensures that stakeholders feel empowered as critical partners in the work.

In the next article in this series, we discuss phase two, which builds on the foundational work of developing a common language and delves into curriculum, grading, selecting learning management systems, and more. The final post discusses phase three on personalizing pathways for students. These phases are intended to be sequential and help practitioners see the value and possibility in intentionally building a solid foundation for mastery.

Learn More:

- Springpoint’s Phased Approach to Implementing Competency-Based Education, Phase Two: Scaling Key Practices and Building Core Systems

- Springpoint’s Phased Approach to Implementing Competency-Based Education, Phase Three: School Schedule and Student Learning Progression

- How Can We “Do School Differently”? Lessons from Springpoint’s StorySLAM at iNACOL

Elina Alayeva is Springpoint’s Executive Director. As a founding leader of Springpoint, she has grown the organization and its offerings to expand reach and impact. Elina has deep expertise in strategic planning and systems-level alignment to enable successful school efforts, technology-enabled innovation, student-centered school models, and organizational operations. Prior to joining Springpoint, she designed and implemented a year-long funding focus on innovative secondary school models as a program officer with Next Generation Learning Challenges. Previously, she worked at Carnegie Corporation of New York as part of its Urban Education program, focusing on new designs for schools and systems. As a Fulbright Fellow, Elina researched ethno-mathematics in community-run schools on First Nations reserves in Canada. Elina currently serves on the advisory board of CompetencyWorks. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Engineering from The Cooper Union and a Master of Arts in Political Science from Columbia University.

Elina Alayeva is Springpoint’s Executive Director. As a founding leader of Springpoint, she has grown the organization and its offerings to expand reach and impact. Elina has deep expertise in strategic planning and systems-level alignment to enable successful school efforts, technology-enabled innovation, student-centered school models, and organizational operations. Prior to joining Springpoint, she designed and implemented a year-long funding focus on innovative secondary school models as a program officer with Next Generation Learning Challenges. Previously, she worked at Carnegie Corporation of New York as part of its Urban Education program, focusing on new designs for schools and systems. As a Fulbright Fellow, Elina researched ethno-mathematics in community-run schools on First Nations reserves in Canada. Elina currently serves on the advisory board of CompetencyWorks. She holds a Bachelor of Science in Engineering from The Cooper Union and a Master of Arts in Political Science from Columbia University.

Christy Kingham is Springpoint’s Director of Leadership and School Design. She works closely with Springpoint’s partners to support the design and implementation of new, student-centered school models. Christy worked with The Young Women’s Leadership School in New York City for eight years as an instructional coach, curriculum developer, and English teacher. She collaborated with colleagues to create robust student supports, design and implement a nationally acclaimed competency system, and implement intensive passion projects. Christy also taught English for seven years at Fox Lane Middle School in Bedford, New York. She graduated from Georgetown University with a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, Columbia University Teachers’ College with a Master of Arts in the Teaching of English, and Hunter College with a Masters in Educational Leadership. She has also been a teacher-leader with the New York City Writing Project and an adjunct professor with Drexel University’s Graduate School of Education.

Christy Kingham is Springpoint’s Director of Leadership and School Design. She works closely with Springpoint’s partners to support the design and implementation of new, student-centered school models. Christy worked with The Young Women’s Leadership School in New York City for eight years as an instructional coach, curriculum developer, and English teacher. She collaborated with colleagues to create robust student supports, design and implement a nationally acclaimed competency system, and implement intensive passion projects. Christy also taught English for seven years at Fox Lane Middle School in Bedford, New York. She graduated from Georgetown University with a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, Columbia University Teachers’ College with a Master of Arts in the Teaching of English, and Hunter College with a Masters in Educational Leadership. She has also been a teacher-leader with the New York City Writing Project and an adjunct professor with Drexel University’s Graduate School of Education.