What is it Going to Mean to Have a Proficiency-Based Diploma?

CompetencyWorks Blog

What is a high school diploma and what does it mean? It certainly isn’t something written in stone – it can be whatever we want it to be. What we need it to be is meaningful to students, parents, colleges, educators, and employers. As we shift to competency education, we have the opportunity and often an urgency to revisit artifacts of the traditional system, either imbuing them with new meaning or redesigning them to better support students and their learning.

What is a high school diploma and what does it mean? It certainly isn’t something written in stone – it can be whatever we want it to be. What we need it to be is meaningful to students, parents, colleges, educators, and employers. As we shift to competency education, we have the opportunity and often an urgency to revisit artifacts of the traditional system, either imbuing them with new meaning or redesigning them to better support students and their learning.

One of the strategies states are using to move toward competency education are proficiency-based diplomas. It’s an interesting strategy. It’s a strategy that demands the diploma mean something rather than an ever-increasing set of required courses and credits. It doesn’t actually say a school has to be competency-based. If they think they can get all their students to the level of proficiency required to earn a diploma in the traditional system, they wouldn’t really have to make any changes, would they? However, districts do start to change immediately to a competency-based or proficiency-based system under this strategy, as they know there is no way they can do it in the traditional system.

As I traveled Maine from Wells all the way to Presque Island last fall, conversations often touched on the issues that are raised by a proficiency-based diploma. As ESSA opens up discussion on accountability and how to create systems that allow our schools, teachers, and students to flourish, we are going to have to explore many of these questions (and more).

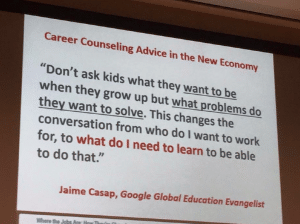

What do we want for our students?

Many districts that transition to competency education start with a conversation with their community about what they want for their students. Although policy has focused on being college and career ready, the language from community members, parents, and students is much broader. There are often references for empowering students, self-directed learning, and lifelong learning. Chugach School District’s mission developed in partnership with community members is below:

The Chugach School District is committed to developing and

supporting a partnership with students, parents, community and

business which equally shares the responsibility of empowering

students to meet the needs of the ever changing world in which

they live. Students shall possess the academic and personal

characteristics necessary to reach their full potential. Students will

contribute to their community in a manner that displays respect

for human dignity and validates the history and culture of all

ethnic groups.

In other districts, there might be reference to 21st century skills (although we are pretty far into the 21st century to be using that phrase) or the 4 Cs: collaboration, creativity, communication, and critical thinking. The movie Most Likely to Succeed, which is being shown in communities, highlights what schools might look like if we were to focus more strongly on these higher order skills.

With the growing movement to eradicate the school-to-prison pipeline (I know educators don’t like this phrase, but if you are an African-American boy caught in it, that’s sure what it feels like), the conversation about what we want for our students is going to have to touch on some of the basics: respect, access to education, and recognizing that children and teens are developing and that behavioral issues are symptoms of something wrong in the school environment, home, or community.

ESSA opens up the conversation to return to what we want for our children…and then the accountability and assessment policies to support it.

If I were to guess where these conversations would lead, it would be some type of combination of:

- Lifelong Learning

- Empowered or self-directed learners with a growth mindset

- Lifelong learning skills that help to navigate new situations and environments

- The four Cs or other ways to communicate deeper learning

- Well-Being

- A positive identify of who they are as learners and members of the community

- Social-emotional learning or the ability to manage one’s emotions effectively in different types of situations

- Healthy and able to take care of their physical and emotional health

- Strong Character

- Strong habits of work and learning

- Ability to negotiate

- Cultural competency and global awareness

- Able to draw on strengths of home culture and values

- Academically Prepared

- Strong foundational skills in math and reading that can be applied to life and open doors to careers

- STEM skills

- Bi-lingual

- Prepared to Earn Income and Pursue Careers

- Understanding of what it takes to get and hold a job (soft skills)

- Strong career development and technical skills

- Prepared to Compete and Succeed in College

- Believe That They Can Succeed, Be Safe, and Change Society for the Better

- Equitable with low-income and students from different cultures and races beating the odds

- Understanding of community, government, and social change

I’m sure I’m missing something. It’s important that we include the wishes from communities that have been most marginalized and underserved so they get embedded into the core of the vision for our students. What would you add to this list?

What are the implications for graduation requirements?

Below is information about three states (are there more?) that have established proficiency-based requirements:

- Colorado has set minimum expectations that are determined by cut scores on a wide range of tests. Districts are expected to set their own requirements.

- Maine expects students to be proficient in a set of eight domains and the guiding principles.

- Vermont’s proficiency-based requirements have seven domains and what they refer to as transferable skills.

What these requirements don’t say is how a district or school is to determine if students are proficient. Nor do they address the multitude of issues that are going to arise from setting proficiency-based diplomas. Let’s look at how districts might establish policies first.

One of the steps that districts will have to take is clarify what it means to have a proficiency-based diploma. Great Schools Partnership has developed resources to support districts in this process. When I visited Wells High School in Maine, they were using GSP’s work on graduation requirements (as is the case in Henry County in Georgia). Here is the link to the GSP overview of verifying graduation requirements and their math and ELA graduation standards.

If we assume that graduation requirements are going to include the 4 Cs, academic skills, a set of habits or behaviors, and success in applying these in some type of projects, experiences, or opportunities, then it is going to take a lot more than saying a number of courses, credits, or passing an academic test.

Many schools use capstone projects, exhibitions, or portfolios that provide evidence that students have met the level of proficiency. In many cases, students are asked to present to an audience of community members, peers, parents, and teachers. (There are tons of resources on portfolios, exhibitions, and capstones. I’m still looking for strong summary pieces that can be shared.)

Another way is to turn to Chugach School District again. They have developed a very clear set of graduation expectations in each domain (see page 35 in the Implementation report). As students progress through school, teachers credential proficiency within the levels. The district also has a role in credentialing that students are ready to move on to the next level. Thus, students are expected to demonstrate and have a portfolio for each level. By the time students graduate, there is confidence that they have the required skills. Accountability and quality control have been embedded into the system itself.

If we draw from other competency-based schools, the question becomes whether we should have stages or phases rather than grade levels – especially at the secondary school level. Schools for the Future and Making Community Connections Charter School (MC²) both use phases that are not time-bound. When students demonstrate that they have met a set of benchmarks, they then move on to the next phase. At MC², students present their portfolios, making the case that they are ready to move on. In some cases, they may receive feedback that they need to continue to strengthen their skills before they do so.

What are the types of issues that are going to develop with proficiency-based diplomas?

There is one question that we are going to have to answer for all students – do we expect every student to meet every standard along the way to meeting the graduation requirement? And are we going to expect every student to meet every proficiency-based graduation requirement? Are we going to not let them graduate if they don’t? That defies common sense to me…but, on the other hand, we don’t want to open the door to inequitable practices where low-income kids or kids of color are granted a diploma without the skills, right?

Align State Policy with Proficiency Goals? What about students who enter high school with elementary school level skills or enormous gaps? Are we going to continue to have a ticking clock for high school that starts when students enroll in ninth grade? Right now, most districts are still dinged if students do not graduate in four years. First things first, we need state level policies that recognize schools and students that help students make the leap from elementary school skills to proficiency-based graduation even if it takes five or six years.

I’m sure there are other elements of state policy that need to be aligned. Ideas?

In-the-Box and Out-of-the-Box Thinking? David Ruff at Great Schools Partnership has been thinking about these issues a lot and believes the answer might be in averaging performance indicators. If students do well enough on a mix of indicators, they are deemed ready to graduate. That certainly seems reasonable.

I’ve been thinking a bit about transparency, growth, and invitations. What if the diploma included information about what level a student reached in each domain? For example, imagine a student enters ninth grade with Level 5 ELA and Level 6 math. After four years, they have gained five years of growth in both subjects, reaching 10 ELA and 11 math, but they still aren’t at graduation requirement levels. Can we graduate that student with a diploma that indicates the levels they reached? And can we invite them to continue to continue learning, focusing in on the specific domains they want until they reach graduation levels?

I’d love to bring the teams from Bronx Arena, Schools for the Future, and Building 21 into this conversation, as I know they would be able to take a look sidewise at these issues and have other insights.

Strategies for Students who Need to Learn Five, Six, Seven, or More Academic Levels Within High School? I do believe that we need to put more focus on increasing learning opportunities for students much earlier as compared to expecting them to stay in high school longer. Who wants to stay in high school longer? We need to build out other strategies – including the transition from eighth to ninth grade, summer academies that have incredibly enriching experiences, and accelerated skill building – and look to ways to integrate domains so students can build multiple skills through the same set of activities. And as always, we have to let go of grade level coverage and meet kids where they are.

Credentialing and Calibrating Proficiency? I am also concerned about districts all setting their own definition of proficiency. I think the state has a huge responsibility to create processes (co-create, I should say) with districts to calibrate what proficiency means. There are going to be some elements of high school proficiency-based graduation requirements that will vary, of course. The goal isn’t cookie-cutter expectations across districts or even across schools. But there does need to be some set of calibration so we don’t fall back down that horrible rabbit hole of inequity.

Digitizing the Diploma? Finally, there is the operational question of what a diploma and transcript look like. Just as districts are experimenting with new report cards, progress report, and real-time information systems to enable conversations with parents, students, and teachers, there are also need to be efforts to rethink what a transcript might look like. As we think about diplomas, we might be able to draw from our colleagues in higher education that are experimenting with digital transcripts that include both courses and competencies and badges.

All of this of course leads to a huge question…

What does it mean for overarching pedagogical philosophy and school design?

This is a topic for another day. One thing is clear, however: It is going to take revamping schools so they develop self-directed learners (student agency). They are going to need performance-based assessments and performance tasks, and they are going to need lots of inquiry-based and applied learning experiences. The future is going to be more interdisciplinary, provide more application opportunities, and, most importantly, meet students where they are and not where we want them to be.

And finally….The question on the mind of all state policymakers…

What does this mean for systems alignment?

As state policymakers consider how they can take advantage of the opportunities offered by #ESSA, we need to think very deeply and critically about how to ensure these issues related to making sure every student receives a meaningful diploma, a proficiency-based diploma.

See also: