Mere Engagement: Reflections about the Connections Between Online Learning, Student Agency, and Student Engagement

Education Domain Blog

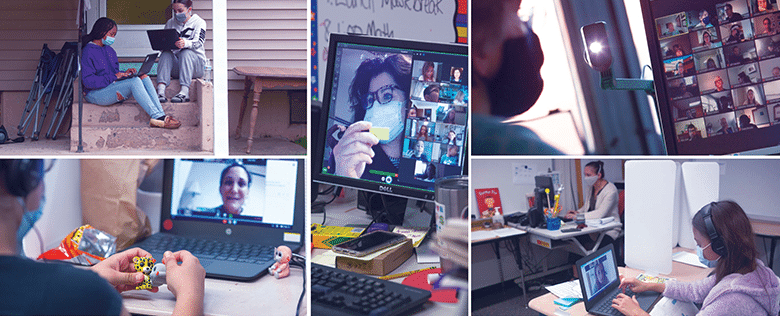

Our circles of family and friends in education are submerged in the academic, safety, and security efforts of continuing a school year like no other in recent history. Teachers, administrators, support staff, and families are thinking about the physical layout of classrooms, hand-washing, masks, temperature-taking, and closing learning gaps. Essential school shopping now includes custom-made masks with sports teams, popular movie characters, or cartoon logos!

Our circles of family and friends in education are submerged in the academic, safety, and security efforts of continuing a school year like no other in recent history. Teachers, administrators, support staff, and families are thinking about the physical layout of classrooms, hand-washing, masks, temperature-taking, and closing learning gaps. Essential school shopping now includes custom-made masks with sports teams, popular movie characters, or cartoon logos!

We get it. Everyone must be concerned about the first two tiers of the Maslow Hierarchy of Needs, as we consider the physiological and safety needs of adults and children during this time of pandemic. However, at some point, we must visit the reality of large numbers of students, wholly or in part, who have moved away from daily face-to-face interaction. Within this context, we must move beyond the logistics and focus on re-establishing relationships and buy-in with students in this “brave new world.”

Big Things Versus Small Things

Our new issue brief, Mere Engagement: Reflections about the Connections Between Online Learning, Student Agency, and Student Engagement, invites reflective thinking as we rise to the challenges of schooling during the pandemic. The word “mere,” based on the Macmillan Dictionary, has two supporting definitions relevant to this conversation. Mere can mean “emphasizing something that is small or unimportant.” It also carries a second meaning, “emphasizing the importance or influence of something – although it only seems like a small thing.”

The big things compete for our attention: most importantly, the wellbeing of all students, adults, and families in the everyday operation of school. Big things also include technical support required for transitioning instruction and assessment to online platforms like Google Classroom, as well as somehow creating and delivering learning support materials to each child’s home. There are lots of big things. Once we become operational, however, the issues linked to the “mere engagement” of our students loom large.

Without considering issues associated with student agency and student engagement, all our work to prepare may be in vain. Engagement has not yet moved to the front burner in our minds. This lack of consideration of mere engagement can be like the story of the nail and the horse’s shoe. As the story goes, the nail was lost, so the shoe was lost, so the horse was lost, and the battle was lost. This small thing can lead to big losses in learning.

Most of us have been involved since March of 2020 with remote schooling, community meetings, and other conversations with friends and family on Zoom or other platforms. There were clearly times and places where virtual schooling worked very well, where connections were made, and learning flourished.

Still, the quick shift to remote or distance learning left little time to plan and prepare for online learning for most schools and districts. The shift was complicated by learning new platforms and tools, navigating student privacy rights, and technical issues like “Zoom-bombing.” Many of us were learners when it comes to the widespread implementation of remote and blended learning.

We are gathering evidence and experience along the way to build a system for our students. If we are to learn from our experience, it is important to get feedback from the stakeholders. We cannot rely on our memories alone. Documented conversations, questionnaires, listening forums—all of those methods and many others can and should be a way to make informed decisions. And we should challenge ourselves to ask the questions along the way: What evidence shall we use to ensure that this is working? What feedback or cues should we be looking for to determine whether students are engaged? How can we ensure student agency is promoted and supported as we design our lessons?

Given the reality of our current environment, it behooves us to take the experiences of last spring, both weak and strong, and share lessons learned. This brief invites readers to share in our reflections about the connections between online learning, student agency, and student engagement.

First Things First

Of primary concern is the wellbeing of our students in the context of these times. Admittedly, we are not psychologists, and we are uncertain of exactly how to define what our students may be feeling. However, there are some things we know for sure. Life for the whole school community shifted dramatically overnight. There is the real possibility that students have experienced or will experience the loss of loved ones to COVID-19.

This school year does not mirror any that we have faced as a student or an educator.

Obviously, we can’t fix what we don’t control, but we must be certain not to exacerbate the fears that we all have in this troubling time. Whether in-class or virtual, it is imperative that we create conditions that stimulate trust. Many schools used advisory periods as a way for students to check in with a trusted adult for support, academically and socially. During advisory periods students could talk about what was working for them and what was not. Students could privately pose questions that could be addressed with the right person in the right context. The need to check in and communicate still exists, and we need to create time and mechanisms for it in virtual situations. To get to the deeper learning required by our students, we will be challenged to change their focus and attention away from the fears of the day, to the learning of the day. Giving students time to build relationships through conversation is one way to give students an outlet.

The phrase, “we do it best when we do it together,” speaks to the need for maintaining and strengthening solid relationships between students, between the adults, and between students and adults. To get to the deeper learning required by our students, we will be challenged to acknowledge their fears and new realities while building support for learning.

Establishing Distance Learning Relationships

Yes, it can be done. Let’s start with that assumption. It’s not a case of being better or worse. It’s a case of recognizing that for many, distance learning is the option they must work with, and that with careful and informed design it is possible to create and sustain the sorts of learning relationships that are critical to success for learning to occur. And, as with each transition from in-class to distance learning, we need to tweak our skill set and apply it to online learning.

Just as we establish roles, relationships and responsibilities for the traditional classroom, it is essential to clarify distance learning roles, relationships, and responsibilities with each of the partners in the learning process: the student, teacher and parent (guardian). This includes the establishment of norms that support optimal distance learning.

Parents, guardians, and students should be given guidance on how best to structure a home-based classroom. Just as you would in the school-based classroom, inviting students to create conditions for learning can be tailored to each student’s circumstance. Creating an “environmental learner profile” can help promote a more optimal time and place for learning.

Some sample questions for the environmental learner profile could include:

- When we are online, can you hear me?

- Is there a quiet space for you and your computer?

- Can you see me on the screen?

- Where in your home is the best place for you to listen and participate?

- Do you know where your assignments are located?

- Do you know how to contact me if you have a question?

- Do you know the schedule for our online classes and how long they will last?

- What would prevent you from joining class?

- Do you have your own computer, or do you share it with other family members?

By baselining each student and their potential for online engagement and gaining insight into the students’ access to technology, level of parent or guardian support, and general sense of comfort with online learning, the partnership for learning can be established on a solid footing. Those with a lot of experience with online learning have found that where schools and teachers had a good understanding of the home context of each learner, and were respectful of that in the way they then designed the learning and connected with the learners remotely, the outcomes were far more fruitful.

Renewing a Sense of Student Agency

We need to provide additional incentives and support to help students move from compliance to authentic engagement during these transitional times. Just showing up, whether it is in class or in remote settings, without real effort to own the learning, will not result in optimal learning outcomes. And generally speaking, without the teacher being physically present, it is more difficult to spontaneously pick up on the small data signals when students are distracted, only partially engaged in the activity, or needing assistance; something that teachers are so skilled at doing in person.

During a transition to remote or distance learning, students need a renewed sense of agency. They must understand what they are to learn and how to demonstrate their learning. They must know how to ask for assistance and exhibit self-direction and efficacy when working on assignments. They own their work and put forth their best efforts. When these attributes of student agency are in play, authentic engagement is occurring.

The expectation to generate a virtual class learning environment affords a unique opportunity to exercise student agency in a broader context. Students may find themselves needing and desiring to solve their own learning environment issues. With so many gathering places closed, a small group of enterprising young people found a way to create a quiet place to read, outside under the shade of trees in the park. Their desire to book-share and the challenge to find a quiet space led them to a pleasant and practical solution. That’s student agency at its best!

In the posts that follow, we provide some concrete ways in which student agency is supported and engagement is strengthened in online learning models. Not unexpectedly, these common-sense ideas are taken from and built on the best practices of the in-class model – and have then been adapted to the online platform.

Laureen Avery is the director of the UCLA Center X Northeast Region office and focuses her work on supporting classroom teachers working with English learners through the ExcEL Leadership Academy. Marsha Jones, was formerly the associate superintendent for curriculum and instruction with Springdale Public Schools and is presently an adjunct professor at the University of Arkansas. Sara Marr is a TESOL teacher and ExcEL coach at the Shelton Public Schools. Derek Wenmoth was until recently a director of CORE Education, a not-for-profit education research and development organization in New Zealand. He is now working independently as an education consultant.