Competency-Based District Leaders on Managing Change During the Pandemic

CompetencyWorks Blog

Headlines during the coronavirus pandemic suggest that many American schools had a disastrous spring in terms of student engagement and learning. At the same time, many personalized, competency-based schools and districts have described smoother and more successful transitions to remote learning. It’s important to understand why. On a recent Aurora Institute webinar, leaders of two outstanding competency-based districts shared lessons learned from their own transitions during the pandemic. The webinar slides and recording are available here.

Lindsay Unified School District

Tom Rooney, superintendent of the Lindsay Unified School District (and a member of the Aurora Institute Advisory Board) presented first. Lindsay is a rural K-12 district in the agricultural San Joaquin Valley in California. All of their 4,200 students qualify for free or reduced price lunch, 93% are Latino, 51% come to kindergarten as English learners, and the average community education level is 5th grade.

Tom Rooney, superintendent of the Lindsay Unified School District (and a member of the Aurora Institute Advisory Board) presented first. Lindsay is a rural K-12 district in the agricultural San Joaquin Valley in California. All of their 4,200 students qualify for free or reduced price lunch, 93% are Latino, 51% come to kindergarten as English learners, and the average community education level is 5th grade.

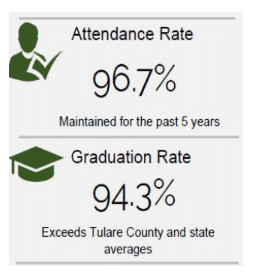

The district’s transition to competency-based education began 10 years ago and has been deep and successful. Students are voting with their feet, with 97% attendance over the past five years, and the high school graduation rate is 98%, exceeding county and state averages. Discipline issues have dropped 65%. Rooney said that not only do 75% of graduates enroll in college, but 54% are earning a college degree in four years, more than 60% in five years, and more than 70% in six years.

The Lindsay school buildings closed on March 17, and Rooney said students were learning actively the next day. A superficial look would make it easy to conclude that this was because all students already had devices and all students had internet access through a community Wi-Fi project that was put in place four years earlier. But it’s important to recognize that having those structural elements in place is a significant achievement in a rural community with families who are struggling economically. Moreover, those elements are not sufficient to engage students in meaningful remote learning.

The Lindsay school buildings closed on March 17, and Rooney said students were learning actively the next day. A superficial look would make it easy to conclude that this was because all students already had devices and all students had internet access through a community Wi-Fi project that was put in place four years earlier. But it’s important to recognize that having those structural elements in place is a significant achievement in a rural community with families who are struggling economically. Moreover, those elements are not sufficient to engage students in meaningful remote learning.

Competency-based education is about deep changes in school structure, culture, and pedagogy, and Lindsay was well-prepared on all three dimensions. The first day they moved to distance learning, all students already knew where they were in their learning progressions and what the next steps were. They already had goals established in their personalized learning plans. And the school had a well-established online learning management system (Empower) that provided access to many of the students’ assignments.

“But what was most important,” Rooney explained, “was that the learners had been taught and lived in a culture where they had been empowered and had become invested. They had developed a mindset where they are responsible for their learning, and they had the tools and the empowerment to navigate their learning journey.” He emphasized the essential competency-based education principle of building a culture where students know they can take ownership of their learning and their future, even in the face of serious challenges.

Finally, a quality curriculum, strong pedagogy, and a culture of professional learning and collaboration played a critical role. The district knew that teachers (Lindsay uses the term “learning facilitators”) needed professional development for effective distance learning. Four days after transitioning to remote learning, a full day of professional learning with 21 breakout sessions enabled staff to begin building needed skills. Then several times per week for the rest of the school year they had virtual professional learning led not just by school and district leaders but also by teachers who were sharing skills and strategies they had developed. Just as the school emphasizes a growth mindset for students, many teachers embraced a growth mindset for remote instruction.

Kettle Moraine School District

Pat Deklotz, superintendent of Kettle Moraine School District in southeastern Wisconsin, was the state’s superintendent of the year in 2016. The district is similar in size to Lindsay, with about 3,900 students, but very different in terms of setting (suburban) and student demographics – 89% white, 13% eligible for free or reduced price lunch, and 1% English learners.

Pat Deklotz, superintendent of Kettle Moraine School District in southeastern Wisconsin, was the state’s superintendent of the year in 2016. The district is similar in size to Lindsay, with about 3,900 students, but very different in terms of setting (suburban) and student demographics – 89% white, 13% eligible for free or reduced price lunch, and 1% English learners.

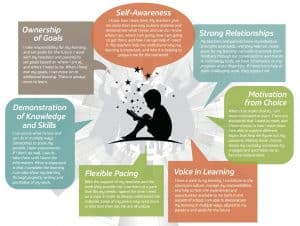

A key commonality between the two districts is a long track record of deeply implementing personalized, competency-based learning. As shown in the figure below and described in Kettle Moraine’s The Student in the Center brochure, the district is devoted to learning that emphasizes student self-direction, voice and choice, relationships, flexible pacing, and demonstrated mastery.

Deklotz emphasized that “Context is everything, and COVID-19 changes everything about our context. But one constant of managing change is that it’s personal, and it’s emotional. So if you don’t recognize those elements as you try to navigate these turbulent waters, you’re going to miss the mark….People need to be heard, and they need to be involved.”

She recommended listening carefully to everyone’s stories and understanding their challenges, such as staff who are working from home and juggling three roles – teaching their students, teaching their children, and parenting. Moreover, many of the goals of competency-based education apply to school staff and parents too: Are we enabling voice and choice? Are we being flexible? Are we setting personalized goals? Are we building relationships?

All students in grades 6-12 already had a device, but students in grades K-5 did not. The younger students received an extra week of vacation (the week before spring break), which gave the school time to survey parents, assess needs for devices and online access, and help the elementary team begin to determine how to meet their students’ virtual learning needs. The school was already using multiple learning management systems, including Canvas, and these were essential tools for their transition to remote learning.

The schools transitioned to a 4-day schedule, where one day was scheduled to be independent project time for students, without oversight from a teacher. School staff used that day for professional development, collaboration among content teams and grade-level teams, and independent planning time. Learning strategies included support with technology tools as well as sitting in on each other’s virtual lessons and providing post-observation feedback.

Deklotz led a daily virtual meeting with all school and district leaders. The agenda was drawn from a shared online document that any participant could add to, and which eventually grew to 50 pages long. She also led a weekly virtual call with parents to convey that she heard their questions and was working on solutions to challenges they raised. One silver lining she pointed out is that she has never seen parents more engaged with and knowledgeable about their children’s learning. They wanted more support, and a key support strategy was re-introducing them to tools and resources that had been available even before the pandemic, such as ways to use the learning management system to support their children’s learning.

Maintaining personal relationships with students was a high priority. Teachers were expected to have direct contact with every student at least once per week through a mix of virtual whole-class meetings, small-group mini-lessons, and one-to-one conferencing. For students who did not engage in learning, the school made progressive outreach efforts—first through the teacher, then the guidance counselor, then the principal. They tried to arrange family meetings focused on how they could meet the student’s needs, emphasizing flexibility and empathy in light of challenges (such as a student needing to care for younger siblings) that were worsened by the pandemic. At the same time that schools were flexible to support student success, they were clear that students did need to engage in order to succeed—there was still accountability.

One interesting reflection from Deklotz was that she didn’t think the district would ever go back to in-person parent conferences. “Zoom meetings or Google Hangouts are much more convenient,” she said, “and they are just as engaging. And when you have the teacher, student, and parent all talking that way, it’s very efficient and effective.” It will be fascinating to see how this plays out over time, and how it may vary across different types of schools, student populations, and staff and family preferences.

Across both Kettle Moraine and Lindsay, the superintendents made it clear that personal connection, flexibility, and positivity played key roles in the success of their pandemic response. When Lindsay saw what was coming, they shifted the narrative, Rooney said. “It was not about closing schools, it was about opening up for learning in a different way.” The district made it clear that “the physical buildings have closed, but the learning, the loving, and the support that you have from your learning community will continue no matter what situation we face going forward.”

Learn More

- Transitioning and Sustaining Competency-Based Education During School Closures

- Virtual Youth Summit Supports Student Agency and Community-Building During COVID-19 School Closures

- Strong Evidence of Competency-Based Education’s Effectiveness from Lindsay Unified School District

- Kettle Moraine: Where the Future of Education is Being Created Student by Student

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.