Strategies and Tools for Remote Learning from the Aurora Institute Member Survey

CompetencyWorks Blog

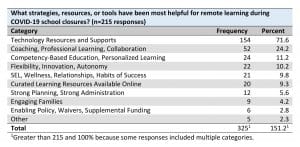

For schools beginning the school year with remote or hybrid learning, this blog post shares what the Aurora Institute learned from our recent member survey in response to the question “What strategies, resources, or tools have been most helpful for remote learning during COVID-19 school closures?” The table below summarizes the responses, followed by details of specific strategies and resources.

Technology resources and supports were mentioned by 72% of respondents, about three times as often as any other category. Ensuring that every student had a device and connectivity was a key priority. Some schools already had one-to-one devices and full connectivity, and others provided additional devices after school buildings closed. Connectivity was increased by buying hot spots for families in need and providing mobile hot spots using school buses in rural communities. Not all needs were met, however, with some families and students unable to access online content and virtual instruction.

When describing resources that have been most helpful for remote learning, respondents named many specific products including Blackboard, Canvas, ClassDojo, Edmentum Exact Path, EdModo, EdPuzzle, FlipGrid, Google Classroom, Google Meet, HyperDocs, Loom, Microsoft Office 365, Microsoft Teams, Moodle, MusicFirst, MyLC, NearPod, Schoology, SeeSaw, Screencastify, Screencast-o-Matic, Summit, WebEx, and Zoom. (The Aurora Institute does not endorse products or companies, but given the unique circumstances of districts moving so quickly to respond to the pandemic, as a resource to the field we decided to share the products that respondents named.)

Technology support was also essential. This was provided by teachers, technology specialists, and family members. A common challenge was needing to remember the usernames, passwords, and procedures for multiple products. One respondent said, “Edmentum’s Exact Path has been fantastic in helping students that need to keep their skills and consolidation of programs to one company or close to one company so parents are not ripping out their hair when having to deal with multiple applications.” Another respondent said, “Google Suite was found to make things really easy for families—the integrations were easy to find and a ‘one-stop shop’ for courses.”

Several respondents said their schools had been one-to-one with devices for years, students and educators were comfortable with learning management systems, and much of their curriculum content was already available online. They described their transitions to remote learning as challenging but relatively simple compared to schools who didn’t already have these structures in place. One respondent from a virtual school said, “Many of our online schools have been reaching out and helping where they could, but there seems to be a historical distrust that is blocking true progress in this area.” A contrasting viewpoint came from a respondent who appreciated the value of “Listening to the veterans of online education who we can actually visit with to help us move beyond importing the same assignments done in the classroom into our learning management system.”

Coaching, professional learning, and collaboration were mentioned by about a quarter of respondents. One common type of collaboration was among teachers within schools, within districts, and across teacher networks in states and nationally. One respondent emphasized the importance of “giving teachers time to work together and rely on each other’s strengths. One teacher is great at creating amazing videos, one is better with lesson planning, and one can dig into our winter assessment data and point out specific, individual/group learning opportunities. Meeting with other teachers more than before the pandemic is a game changer and needs to continue!”

Another respondent was part of a team of three specialists in the district who were trained and available to manage the district’s learning management system. They said, “We jumped in and did training on a slew of topics the minute schools were forced to close. We also offered daily open office times for our teachers to teach out for help.” Strong planning and facilitation of professional learning was important, such as creating specific times and resources for collaboration.

Intermediary organizations that support quality professional learning also played a key role. This included technology training as well as providing resources on school culture, structure, pedagogy, communications, planning, and design for remote learning. Webinars and YouTube videos were helpful on topics ranging from specific technology tools to district budget and federal policy issues. Specific supports and organizations mentioned included Catlin Tucker’s books on blended learning, DLAC web resources, Georgia Virtual School tools and training, Global Online Academy courses, and Aurora Institute papers on effective blended learning.

Personalized, competency-based education, as well as the three subsequent topics below, were each mentioned by about 10% of respondents. A common theme was that schools that had invested in student agency and self-direction, deeper learning, and project-based learning before the pandemic enjoyed a smoother transition to remote learning. One respondent wrote, “Our switch to competency-based learning as the primary focus of our schools was critical. It allowed for online tools to be a means to cover state standards while freeing up teachers to continue with project-based work that evaluated progress on competencies even in a virtual environment.”

Another respondent wrote, “Having clear required competencies with aligned assessments was essential. So was the fact that our LMS housed thousands of playlists for learners to access learning, combined with a comprehensive system of reporting progress and giving feedback.” Additional competency-based education strategies included flexible scheduling, flexibility and creativity in how students demonstrate their learning, and having students and teachers meet in diverse configurations. One district is using the crisis as a catalyst for competency-based education, saying “We are developing a set of 7-8 personalized, competency-based learning practices that we will adhere to as a district to continue pushing our momentum forward whether we are virtual, face-to-face, or a hybrid model next year.”

Flexibility, autonomy, and innovation took a variety of forms, including those mentioned earlier, such as scheduling, student groupings, and how students demonstrated their learning. Other aspects of flexibility were with deadlines and “concentrating on base standards.” A wonderful aphorism for the flexibility needed during the pandemic was “Grace Before Grades”—a stance that competency-based education supports at non-crisis times too.

Autonomy included “collaborative team leadership that allows our team to be responsive to our students’ needs without layers of approval,” and also, to some extent, the ability to be “tight on criteria, loose on path.” Comments about innovation included “creative instruction,” “ad hoc solutions from educators,” “teachers and students thinking outside the box,” and “public educators coming together to work toward educating our children by any means necessary.”

Social-emotional learning, wellness, and relationship strategies included advisory programs, SEL-infused course work, promoting “growth/belonging/value mindsets,” well-being calls from teachers and social workers (sometimes combined with academic check-ins), and referring students and families to safety-net resources. Respondents argued for “recognizing relationships as foundational” and that “a relational focus keeps the learning meaningful.” Videoconferencing was seen as an important strategy for keeping relationships intact, with an “unrelenting focus on maintaining a community of learners in each virtual classroom.” As with some of the other categories, foundations laid before the pandemic with advisory programs and social-emotional learning were seen as key to success during remote learning. One comment emphasized that school staff and their families need human resources and SEL support too.

Curated Learning Resources – Access to free, high-quality instructional resources that are vetted and curated by trusted organizations and presented online or via cable television in a convenient format were noted as key resources by many respondents. Sources of these resources included local and state education agencies, local cable channels, textbook publishers, YouTube, and unnamed online learning repositories and platforms. Specific resources suggested included Engaging All Learners, Khan Academy, ISTE, SETDA, and the Jefferson County (Kentucky) Choiceboard platform. Helpful characteristics of these materials were being aligned to standards, downloadable into learning management systems, available free of charge, and accompanied by clear planning guidelines. One respondent noted that “Lists of ‘best practices’ or articles about ‘the top 5 ways to . . . . .’ always help clarify my focus.”

The remaining topics were mentioned by 3-6% of respondents:

- Strong Planning and Administration included clear and streamlined communications among school and district administration, teachers, students, and families; guidance plans for remote learning; consistent instruction and assessment practices and use of technology tools across the school; and consistent routines and meeting times for staff and students.

- Engaging Families included providing support to parents through phone calls and videoconferencing, resource and activity bags, and helping them find effective online resources. Respondents emphasized the importance of “engaging parents and families as key partners in their child’s education.”

- Enabling Policy and Funding included access to CARES Act funding that brought needed devices and connectivity to students, as well as waivers from state and federal policies (e.g., seat-time requirements) that allowed for more flexibility in teaching and learning.

Learn More

- Transitioning and Sustaining Competency-Based Education During School Closures

- Competency-Based District Leaders on Managing Change During the Pandemic

- Silver Linings: Observations of Self-Directed Behavior in an Online Environment

- Virtual Youth Summit Supports Student Agency and Community-Building During COVID-19 School Closures

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.