Professional Learning Exercises for Teachers Making the Shift to Equitable, Learner-Centered Education

CompetencyWorks Blog

Follow the journey of Learning Community Middle School, a fictional school that represents an amalgam of schools on the learner-centered journey, derived from the collective field experiences of report authors Kim Carter and Andrea Stewart. These specific exercises and resources are designed to be used and adapted for your context to make the ideas in the Teachers Making the Shift to Equitable, Learner-Centered Education: Harnessing Mental Models, Motivations, and Moves report actionable in schools, districts, and states. While each school and district will have its own context of past work and community assets to build on, the exercises in this guide illustrate an example path a teacher learning community might follow or adapt.

Photo Credit: iStock.com // FatCamera

Photo Credit: iStock.com // FatCamera

Learning Community Middle School Makes the Shift

The Learning Community Middle School (LCMS) is an urban school with a learner-centered focus. LCMS recently adopted the Educator Competencies for Personalized, Learner-Centered Environments to guide professional growth and schoolwide improvement. To kick off this work, the school completed an Equity Audit to expose any racial inequities and use data to understand gaps.

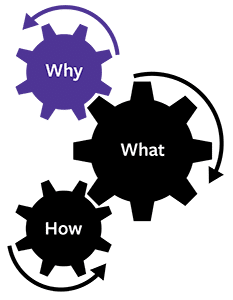

Using the equity audit results, the LCMS team learned together, guided by an understanding of the hidden drivers of changing teacher practice. In this imagined case study, the work unfolded from the Why to the What to the How over the course of two school years. Making progress in shifting to learner-centered practices was a priority and the primary focus of professional learning, supported by the leadership and instructional coach. Following the initial implementation of adult-driven professional learning, the cycles continue iteratively throughout the five-to-seven-year change process.

These exercises assume familiarity with the report framework, which is also summarized in this blog post. As you explore each area, remember that these strategies do not happen in isolation. Rather, the strategies designed to address the why, the what, and the how are interwoven.

Why Story: How one school harnessed emotions and motivations to help drive change

Based on the equity audit, a professional learning steering committee recommended that all teachers engage with an overarching equity practice from the audit during the next learning cycle. They chose the equity practice, “analyzing their own interactions with students to determine any differential patterns, and taking actions to counteract and balance differences.”

Based on the equity audit, a professional learning steering committee recommended that all teachers engage with an overarching equity practice from the audit during the next learning cycle. They chose the equity practice, “analyzing their own interactions with students to determine any differential patterns, and taking actions to counteract and balance differences.”

Expand each section to follow the LCMS story, explore the tools and resources they used, and see the related Educator Competencies. Learn about the science behind these exercises in the blog post, Caution: Change Ahead! How Harnessing Emotions and Motivations Can Help Drive Change for Equitable, Learner-Centered Education.

Relevance: Engage educators in their own inquiry process to identify the problem of practice

A learner’s interest and motivation are piqued when learning tasks are perceived to be relevant to current contexts. To increase the relevance of their work, LCMS embarked on their own inquiry process to identify a problem of practice.

A learner’s interest and motivation are piqued when learning tasks are perceived to be relevant to current contexts. To increase the relevance of their work, LCMS embarked on their own inquiry process to identify a problem of practice.

First, LCMS educators were invited to a Data-Driven Dialogue with their colleagues to explore the results of their learner perception surveys. Their review of survey findings revealed disparities by race in learners’ reports of feeling engaged and challenged, with learners of color reporting lower rates of these desired experiences.

Dismayed by these unexpected findings, educators then used the Identifying an Equity Problem protocol during which they engaged in a Root Cause Analysis to identify ways to address racial discrepancies in perceived engagement and challenge as a problem of practice for which the school community will create solutions. For LCMS educators, the relevance of their problem of practice was enhanced by having discovered these discrepancies for themselves. Note: Perceptions of relevance were further heightened at a later phase in the process when educators were encouraged to identify their own problem of practice related to the schoolwide focus in their own work using self-assessment, reflection and feedback.

Receptivity: Create a safe space for confronting misconceptions and implicit bias

Harnessing educators’ positive feelings of interest and relevance represents only one side of the emotional equation. To ensure receptivity for change, educators also need social support and a safe space to process less positive feelings as well. To prepare educators for these challenging conversations, Learning Community Middle School (LCMS) first established a climate of trust by investing time in:

Harnessing educators’ positive feelings of interest and relevance represents only one side of the emotional equation. To ensure receptivity for change, educators also need social support and a safe space to process less positive feelings as well. To prepare educators for these challenging conversations, Learning Community Middle School (LCMS) first established a climate of trust by investing time in:

- Developing Community Agreements,

- Understanding the value of protocols as containers for challenging conversations (Why Protocols?), and building

- foundational awareness (Exploring Identity Markers),

- relationships (How to Build Trust), and

- skills for staying in important conversations (Constructivist Listening Dyad).

Next, LCMS educators organized themselves into smaller professional learning communities (PLCs). As they dug deeper into the potential root causes for racial discrepancies (see relevance), they helped prepare educators for more honest reflection and sharing by using the ProMISE Protocol and the Equity-Centered Critical Friends Partners Protocol.

By giving educators a socially supportive and emotionally “safe space” to openly talk about their misconceptions, assumptions and biases LCMS educators were able to recognize that they had been inadvertently holding some students back based on the belief that they were “meeting students where they were.” This meant that teachers were not always offering students sufficient challenge and may have been communicating lower expectations.

Agency: Enable educators to make decisions and guide their own professional growth

Educators’ initial motivation to tackle a problem of practice can quickly fade unless they can find ways to integrate the work with their own instructional goals, interests, and professional identity. Giving teachers the opportunity to make decisions about the focus and direction of the work can fuel their self-determination, help preserve their sense of integrity and professional identity, and enable them to persevere through times when they experience a loss in confidence and productivity as they shift and grow new practices.

Educators’ initial motivation to tackle a problem of practice can quickly fade unless they can find ways to integrate the work with their own instructional goals, interests, and professional identity. Giving teachers the opportunity to make decisions about the focus and direction of the work can fuel their self-determination, help preserve their sense of integrity and professional identity, and enable them to persevere through times when they experience a loss in confidence and productivity as they shift and grow new practices.

The Learning Community Middle School (LCMS) used several strategies to help build educator agency and integrate the work with their sense of competence and identity. First, they used the Voice in Decisions Technique (VIDT) process from the Right Question Institute to help teachers ask questions about the principal’s decision to use a PDSA model to guide the work going forward. This step honored their professional learning community’s collective commitment to integrate teacher voice in the change and improvement process.

What Story: How one school uncovered and refined mental models to guide change

Despite concerted efforts to implement learner-centered practices prior to this work, educators were dismayed but not surprised to discover racial discrepancies in student reports of engagement and challenge from their Why Story inquiry. The results of a root cause analysis revealed that teachers had been inadvertently holding students back with low expectations, offering lower levels of challenge and more limited opportunities—particularly for students of color—to make decisions about their own learning. To support teacher growth in response to these findings, the LCMS professional learning steering committee selected four competencies related to enhancing student engagement and challenge from the Educator Competencies for Personalized, Learner Centered Environments. Next, they crosswalked these competencies with equity-centered practices from their Equity Audit. This framework provided a common focus while still allowing for adult learner agency.

Despite concerted efforts to implement learner-centered practices prior to this work, educators were dismayed but not surprised to discover racial discrepancies in student reports of engagement and challenge from their Why Story inquiry. The results of a root cause analysis revealed that teachers had been inadvertently holding students back with low expectations, offering lower levels of challenge and more limited opportunities—particularly for students of color—to make decisions about their own learning. To support teacher growth in response to these findings, the LCMS professional learning steering committee selected four competencies related to enhancing student engagement and challenge from the Educator Competencies for Personalized, Learner Centered Environments. Next, they crosswalked these competencies with equity-centered practices from their Equity Audit. This framework provided a common focus while still allowing for adult learner agency.

Expand each section to follow the LCMS story, explore the tools and resources they used, and see the related Educator Competencies. Learn about the science behind these exercises in the blog post, Sabotage! How Our Implicit Biases and Mental Models Keep Us From “Walking the Talk.”

Surface: Explicate mental models

LCMS educators were motivated to explore why students of color were reporting low engagement and insufficient challenge. Within their selected PLCs, educators engaged in a series of exercises to explicate their implicit theories and assumptions related to “engaging and challenging” students. First they looked at the educator competencies [crosswalk] to identify practices relevant to this issue. One of the PLCs selected the KnowledgeWorks/CCSSO educator competency “Ask challenging and engaging questions to develop higher-order and critical thinking skills.”

LCMS educators were motivated to explore why students of color were reporting low engagement and insufficient challenge. Within their selected PLCs, educators engaged in a series of exercises to explicate their implicit theories and assumptions related to “engaging and challenging” students. First they looked at the educator competencies [crosswalk] to identify practices relevant to this issue. One of the PLCs selected the KnowledgeWorks/CCSSO educator competency “Ask challenging and engaging questions to develop higher-order and critical thinking skills.”

These LCMS teachers developed Concept Maps with a partner to increase awareness of the “what, why, and how” associated with asking challenging and engaging questions. Then, educators expanded their concept maps into a Thinking Map where they illustrated their theories about the causal relationships between educators’ use of questioning techniques and anticipated students’ feelings, understandings, and actions. A key part of this process was uncovering implicit assumptions and beliefs underlying their theories.

Through these exercises, many educators shared a belief that they were “meeting students where they were” when they set their expectations for the level of rigor for each student. Some educators explained that they feared that if pushed, some students might not rise to meet higher expectations. Others felt that if students were left to struggle on their own, this might dampen student interest and motivation. Since emotions were running high during these exercises, the facilitators periodically used Constructivist Listening Dyads to help teachers process their thoughts and emotions.

Align: Address misconceptions using predictions and observations

To help LCMS educators check the validity of their thinking maps, they collected data to determine whether evidence from their practice would uphold their professed theories (i.e., prediction). After PLC members conducted brief classroom trials and engaged in peer observations, they met to discuss and reconcile their initial theories with their actual results through Consultancies. For many LCMS teachers, for instance, their theories regarding students’ anticipated avoidance of higher challenge activities were not confirmed.

To help LCMS educators check the validity of their thinking maps, they collected data to determine whether evidence from their practice would uphold their professed theories (i.e., prediction). After PLC members conducted brief classroom trials and engaged in peer observations, they met to discuss and reconcile their initial theories with their actual results through Consultancies. For many LCMS teachers, for instance, their theories regarding students’ anticipated avoidance of higher challenge activities were not confirmed.

Expand: Shift theories using analogies and metaphors

LCMS educators surfaced their tacit knowledge and beliefs of the dynamic relationship between greater challenge and student engagement and effort through creating an image, metaphor, or analogy. Using the Creating Metaphors protocol educators shared their metaphors. Next, they drew on examples from others to further refine their personalized metaphor. Then the participants presented their refined metaphors, having listeners draw visual representations of what they heard the presenter say. Listeners shared their visual representations during the response rounds, before giving the presenter a chance to reflect on their own emerging thinking. During the course of this learning cycle, educators were encouraged to revisit and revise their metaphors as they progressed in their understanding over time.

LCMS educators surfaced their tacit knowledge and beliefs of the dynamic relationship between greater challenge and student engagement and effort through creating an image, metaphor, or analogy. Using the Creating Metaphors protocol educators shared their metaphors. Next, they drew on examples from others to further refine their personalized metaphor. Then the participants presented their refined metaphors, having listeners draw visual representations of what they heard the presenter say. Listeners shared their visual representations during the response rounds, before giving the presenter a chance to reflect on their own emerging thinking. During the course of this learning cycle, educators were encouraged to revisit and revise their metaphors as they progressed in their understanding over time.

Guide: Craft a theory of action to guide changes in practice

With a clearer idea of the factors and dynamic relationships between increased challenge and student engagement and effort, LCMS educators were now ready to craft a more specific theory of action to guide their improvement efforts. Using their Concept and Thinking Maps, along with their problem of practice and perceptual data, PLC members worked collaboratively within their groups to create a preliminary Theory of Action. LCMS teachers were particularly mindful of addressing the role that learner agency would play in the selected strategies to improve learner challenge and engagement. Note: Depending on prior knowledge, teachers may need to complete the theory of action and some professional learning in rapid cycles to make a plan for improvement.

With a clearer idea of the factors and dynamic relationships between increased challenge and student engagement and effort, LCMS educators were now ready to craft a more specific theory of action to guide their improvement efforts. Using their Concept and Thinking Maps, along with their problem of practice and perceptual data, PLC members worked collaboratively within their groups to create a preliminary Theory of Action. LCMS teachers were particularly mindful of addressing the role that learner agency would play in the selected strategies to improve learner challenge and engagement. Note: Depending on prior knowledge, teachers may need to complete the theory of action and some professional learning in rapid cycles to make a plan for improvement.

How Story: How one school helped teachers build new moves and shift habits to sustain change

By exploring and testing out their implicit theories and assumptions (i.e., mental models) about how students respond to increased challenge, many educators realized that under the guise of “meeting students where they were,” they had been giving students of color insufficient challenge and a limited role in decision making. Recognizing that they had been inadvertently holding lower expectations for some learners than for others, educators created theories of action grounded in new practices that would keep expectations for all learners high (e.g., “If we _____, learners will _____, so that ______.” They made their previous habits visible and enacted strategies to solidify new practices in order to sustain change over time.

By exploring and testing out their implicit theories and assumptions (i.e., mental models) about how students respond to increased challenge, many educators realized that under the guise of “meeting students where they were,” they had been giving students of color insufficient challenge and a limited role in decision making. Recognizing that they had been inadvertently holding lower expectations for some learners than for others, educators created theories of action grounded in new practices that would keep expectations for all learners high (e.g., “If we _____, learners will _____, so that ______.” They made their previous habits visible and enacted strategies to solidify new practices in order to sustain change over time.

Expand each section to follow the LCMS story, explore the tools and resources they used, and see the related Educator Competencies. Learn about the science behind these exercises in the blog post, Old Habits Die Hard: How to Build New Moves and Habits to Sustain Change.

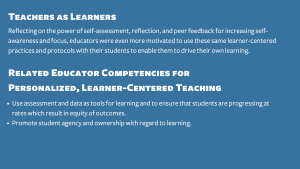

Assess: Assess current practices through reflection and seeking structured feedback

PLCs shared their theories of action and sought feedback using the Giving and Receiving Feedback tenets. Educators then returned to their PLCs to study the Educator Competencies for Personalized, Learner-Centered Environments and take steps to determine their assets and areas for growth as they began implementation. Educators were then introduced to Learning Couture’s Customizing Learning Platform, where they created their own Learner Profile and completed a self-assessment of their practices. The principal chose this platform to foster an asset-based growth orientation with adult learners, grounded in universal design and culturally-responsive teaching and learning practices, so the teachers could experience these practices firsthand while using them with students. This process also included designing a personalized learning plan, including setting a learning intention, determining how best to access and engage in new learning through resources and collaborative activities, and expressing that new learning by applying it to instructional practices.

PLCs shared their theories of action and sought feedback using the Giving and Receiving Feedback tenets. Educators then returned to their PLCs to study the Educator Competencies for Personalized, Learner-Centered Environments and take steps to determine their assets and areas for growth as they began implementation. Educators were then introduced to Learning Couture’s Customizing Learning Platform, where they created their own Learner Profile and completed a self-assessment of their practices. The principal chose this platform to foster an asset-based growth orientation with adult learners, grounded in universal design and culturally-responsive teaching and learning practices, so the teachers could experience these practices firsthand while using them with students. This process also included designing a personalized learning plan, including setting a learning intention, determining how best to access and engage in new learning through resources and collaborative activities, and expressing that new learning by applying it to instructional practices.

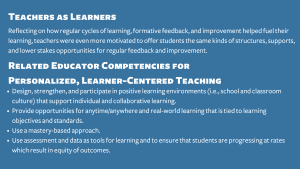

Grow: Developing targeted skills through personalized, flexible, job-embedded professional learning

Throughout the PDSA process, LCMS educators discovered more about themselves as learners by completing a learner profile and identified knowledge and skills they wanted to expand through their asset scans. Teachers then chose learning opportunities that fit their target strategies, context, modality preferences, and learning needs. Learning opportunities ranged from playlists to modules to micro-credentials from Digital Promise or to other resources where teachers learned about the strategies they planned to implement in their Theory of Action. Example resources that support both the adult learners’ needs and the focus on engagement and challenge included:

Throughout the PDSA process, LCMS educators discovered more about themselves as learners by completing a learner profile and identified knowledge and skills they wanted to expand through their asset scans. Teachers then chose learning opportunities that fit their target strategies, context, modality preferences, and learning needs. Learning opportunities ranged from playlists to modules to micro-credentials from Digital Promise or to other resources where teachers learned about the strategies they planned to implement in their Theory of Action. Example resources that support both the adult learners’ needs and the focus on engagement and challenge included:

- If Equity Is a Priority, UDL Is a Must (podcast)

- Facilitating Learning in a Student-Driven Environment (video)

- Question Formulation Technique Steps and Video Guide and the Lesson Planning Workbook

- Anti-Bias Instruction (micro-credential)

- Social Justice Talk: Strategies for Teaching Critical Awareness (book)

Experiment: Test and affirm new practices through iterative cycles of experimentation

Working in their selected PLCs, LCMS educators used the Educator Competencies’ Reflection Tool for Prioritized Competencies as a model to reflect and then create look-fors tied to the strategies in their Theory of Action. Using the Giving and Receiving Feedback tenets, teachers sought feedback from their peers to select look-fors and determine quality criteria for implementation during instructional cycles. Next, they engaged in rapid cycles of experimentation using a PDSA cycle to build new moves. To ensure accountability and support, each educator chose a partner to meet with each week to discuss application of new knowledge, skills, and dispositions, to observe (Classroom Observation Tools and Techniques) each other’s practice, or to plan refinements to improve practices.

Working in their selected PLCs, LCMS educators used the Educator Competencies’ Reflection Tool for Prioritized Competencies as a model to reflect and then create look-fors tied to the strategies in their Theory of Action. Using the Giving and Receiving Feedback tenets, teachers sought feedback from their peers to select look-fors and determine quality criteria for implementation during instructional cycles. Next, they engaged in rapid cycles of experimentation using a PDSA cycle to build new moves. To ensure accountability and support, each educator chose a partner to meet with each week to discuss application of new knowledge, skills, and dispositions, to observe (Classroom Observation Tools and Techniques) each other’s practice, or to plan refinements to improve practices.

Sustain: Make habits visible and reinforce desired shifts

As LCMS educators engaged in rapid cycles of experimentation, they used the Ladder of Inference to remind themselves of their mental models and to increase their receptivity to the structured peer coaching protocol, The Ladder of Inference Questioning Strategies. They did this every two weeks during meetings with their partners in order to continually surface mental models and existing habits. Teachers experienced cognitive dissonance as they discovered unwanted habits that were slowing their progress. Working with their partners using the Giving and Receiving Feedback tenets, educators intentionally worked to shift these undesirable habits through resources such as How to Form a New Habit and How to Change a Habit, or by choosing several of these 18 tricks. Note: Additional job-embedded professional learning was needed throughout the learning cycle as teachers continued to refine their practice.

As LCMS educators engaged in rapid cycles of experimentation, they used the Ladder of Inference to remind themselves of their mental models and to increase their receptivity to the structured peer coaching protocol, The Ladder of Inference Questioning Strategies. They did this every two weeks during meetings with their partners in order to continually surface mental models and existing habits. Teachers experienced cognitive dissonance as they discovered unwanted habits that were slowing their progress. Working with their partners using the Giving and Receiving Feedback tenets, educators intentionally worked to shift these undesirable habits through resources such as How to Form a New Habit and How to Change a Habit, or by choosing several of these 18 tricks. Note: Additional job-embedded professional learning was needed throughout the learning cycle as teachers continued to refine their practice.