Strategies for Responsive Pacing at the Success Center

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second post in a series about Opportunity Academy in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

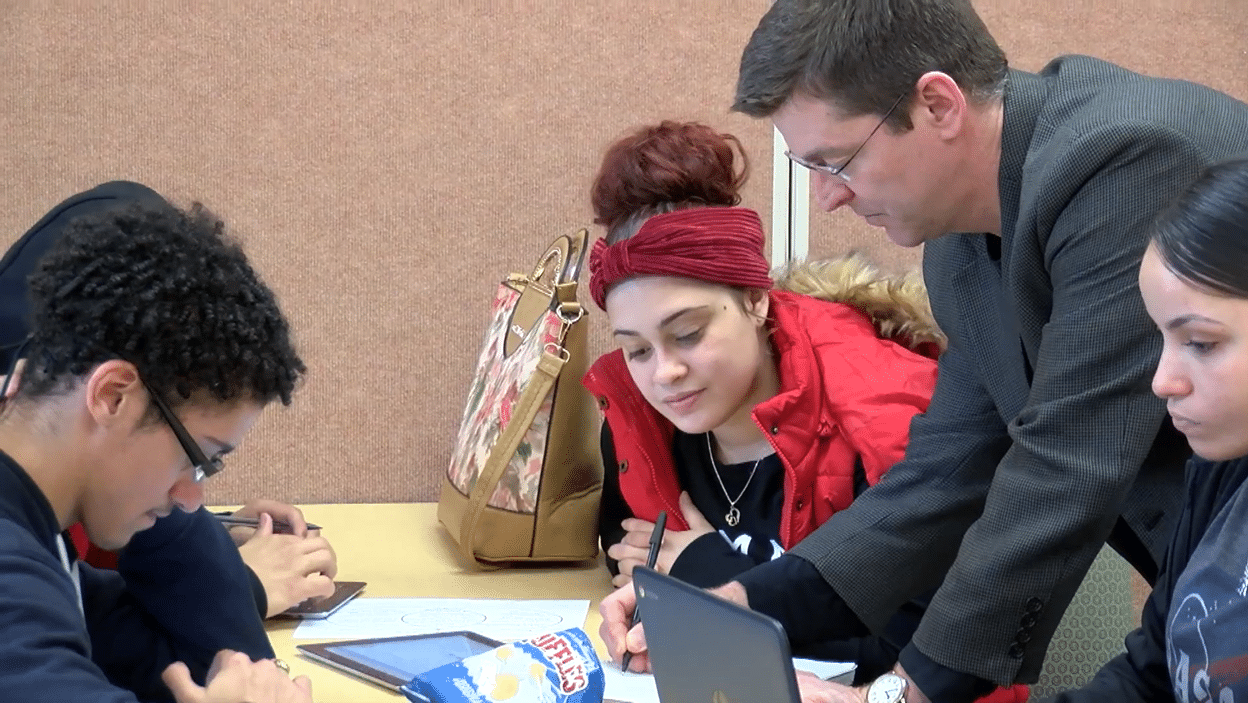

Image: Holyoke Public Schools

The Success Center at Opportunity Academy has many practices that support responsive pacing, a key element of competency-based education (CBE). Students in competency-based schools advance when they demonstrate mastery, not based on seat time, so pacing varies from student to student. Different CBE schools support responsive (or “varied” or “flexible”) pacing in different ways, and the Success Center provides a model that relies on student agency, innovative course structures and scheduling, and a variety of student supports.

Course Structures and Scheduling that Support Responsive Pacing

As explained in the previous blog post, much of the learning at the Success Center happens through project-based “transformative learning experiences” (TLEs). Each teacher also offers what they call “skills-based courses” that are not project-based, last roughly two weeks, and focus on a small number of “attainments” and “micro-attainments”—the subcompetencies and smaller learning targets within the Success Center’s set of broader competencies. These courses focus on academic content, skills, and habits of success.

The Success Center also has a learning lab where students can receive tutoring and support on any subject, and all students have learning lab time in their weekly schedule. Students can take online courses at the learning lab, although Schmidt said that the Success Center is using this option much less than in the past and that teachers provide ample supports for online courses.

Innovative scheduling supports these different learning structures. Every day but Wednesday has four 75-minute blocks beginning at 9:00 a.m., 10:15 a.m., 11:30 a.m., and 12:45 p.m., followed by a 60-minute block that begins at 2:00 p.m. Students can select any one of these blocks as a “lunch” block or schedule a class during every block if they’re trying to accelerate. Many students who drop a sibling off at school miss the first block of the day, and some students who have jobs miss the final block. Students often use the shorter 2:00 p.m. block to go to the learning lab or “drop in” on teachers for extra support.

Wednesdays are flexible “workshop time,” with no scheduled course meetings. In the morning, students meet with their advisor to make a plan for the day. They have to check in with every teacher at some point during the day, but they decide how to spend the day to maximize their progress. They can make up missed work, go deeper in an area of strong interest, have one-to-one meetings with teachers, complete assessments, or spend time in the learning lab. The day ends early, at 12:45 p.m., when students leave and staff begin an afternoon of planning and professional learning.

Attendance is a serious challenge at the Success Center. “That’s why many of the kids are here,” one teacher said. While the school has a variety of strategies to encourage attendance, including a team of engagement specialists, the scheduling and learning structures are also designed to enable students with low or intermittent attendance to make gradual progress rather than dropping out.

“Some of our students who make the most progress academically are not the ones who are present 100% of the time,” principal Geoffrey Schmidt said. “Using our competency-based model rather than seat time is necessary for many of our students. Many of them come here because they can’t or won’t or don’t know how to play the game of school. So our adaptable schedule is essential, and so is the fact that students earn micro-attainments each day and don’t lose them if they happen to miss a week down the road. You don’t get credit at the end of the cycle based on the whole scope of what you’ve done, which could sink you based on attendance alone. You get it for the work you do when you’re here, or even, for many of them, when they’re not here.”

Students with lower attendance—missing many days or even leaving for weeks or months—may return to school in the middle of an eight-week TLE and not really be able to make substantial progress on project-based work until the next TLE session starts. However, it will be two weeks at most before the next skills-based courses start, and in the meantime they can be in the learning lab working on attainments they had partly completed previously or new ones. Sometimes, with additional support from the learning lab, students are able to join a TLE or skills-based course in mid-session.

“We all teach a class that’s theoretically ‘attendance-proof,’” one teacher said. “You can work on it when you’re here, and absences don’t compound in the same say. And we’re on a two-month cycle, so if you miss something you can pick it up again. There are opportunities to plug back in.” He contrasted this to a traditional model where students may have to wait until the next year or redo an entire course if they miss certain learning opportunities or assessments.

Principal Schmidt added, “It’s about building a schedule that can support students with low attendance while also making sure that our most engaged and regularly attending students are also adequately challenged, regardless of skill level, and that all students get the core knowledge they need.”

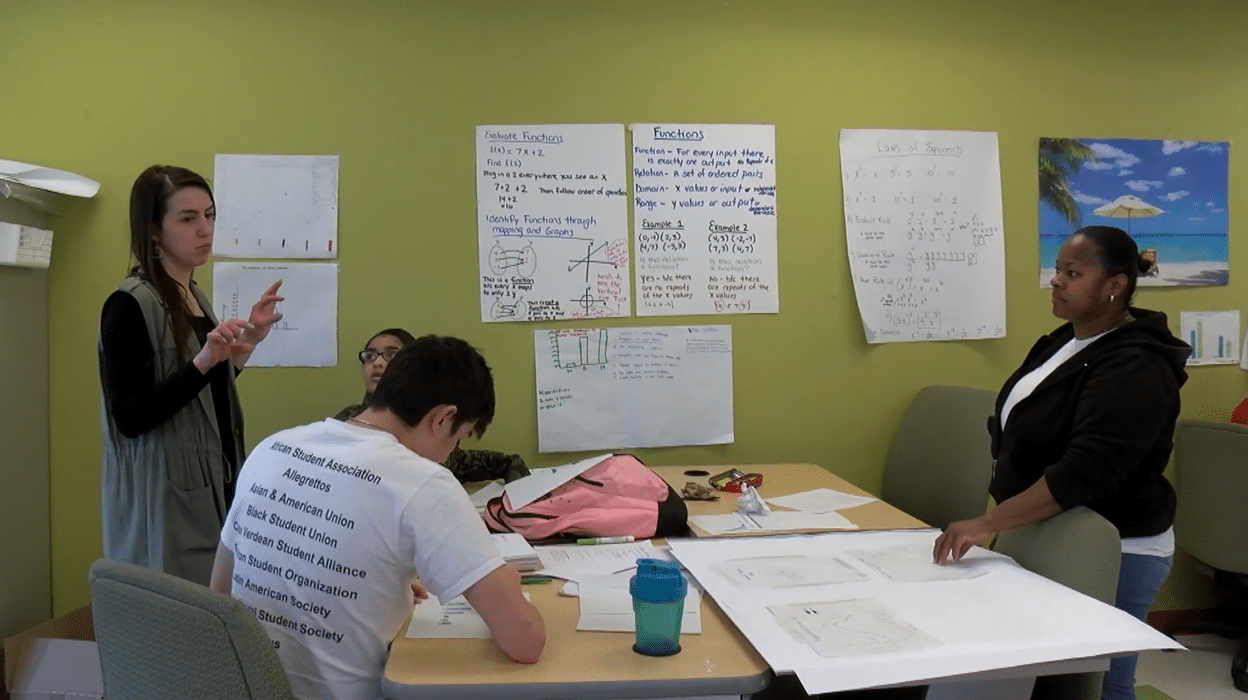

Image: Holyoke Public Schools

Agency and Student Supports

Clearly this model places considerable responsibility on students, which is consistent with CBE’s emphasis on student agency and developing habits of success such as collaboration, communication, and self-direction. But the model also provides supports to help students build these habits over time.

Case conferences with advisors are one essential type of support. Describing a case conference on a Wednesday workshop day, one teacher said, “I’d meet with one of my students in the morning. I’d say, ‘OK, let’s dive into what your next steps are on Integrated Lit. We set goals around that, and we’ll do that for each of his classes. Then it’s his responsibility. He’s got the sheet that says who he needs to check in with. He brings it to the teacher. The teacher says, ‘Here’s what we’re doing today. To make progress you have to look at the feedback I gave you on this assignment, which is tied to a particular competency.’ The student will work on that, then the teacher will check him out, and he’ll move on to the next class, doing all of this at his own pace. For students who don’t use a Wednesday well, we’ll have a case conference with them on Thursday and talk about what they left on the table yesterday.”

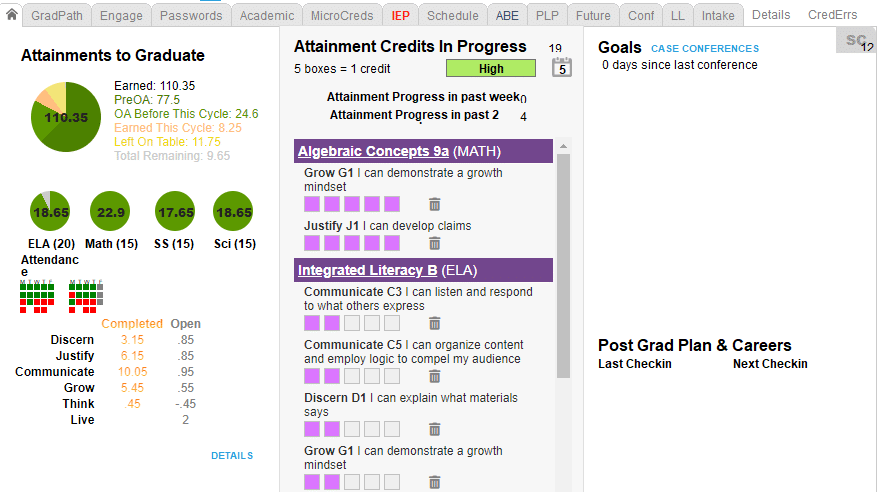

Effective case conferencing also requires transparent systems for tracking students’ academic progress and engagement. The Success Center uses a FileMaker database with a variety of dashboards (see image below) that a local software developer has built for them over time. They want a system that helps students set goals and track their own progress with strong visual cues. As with many CBE schools, the Success Center has found that no commercially available learning management system has all the features they want. At the same time, they see the limitations of their homegrown system and are trying to decide whether to shift to a commercial product.

Finally, the Success Center provides strong socioemotional supports. Part of this comes from the advisor and engagement specialists, who help students navigate both academic and non-academic challenges. The Success Center has also partnered with Alianza, a local group of clinicians that created a practice to serve students at the Success Center and opened an office in the same building.

In addition to individual and group therapy, Alianza uses a “from pain to power” model through which, Schmidt explained, students help to “carry the trauma-informed, socioemotional learning, and restorative justice culture for our school, and are the ones who educate us and help us develop the system.” The seed funding for this work came from the Barr Foundation’s Engage New England grant described in the previous blog post. Now most of the funding comes through MassHealth, the Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program in Massachusetts, which covers most Success Center students.

In traditional K-12 schools, time is the constant and learning is often variable. Competency-based schools strive for rigorous learning to be the constant, which requires time to be variable. The Success Center at Opportunity Academy provides an outstanding example of the intertwined elements of structure, culture, and pedagogy that make responsive pacing possible and powerful.

Learn More

- The Primary Person Model and Transformative Learning Experiences at Opportunity Academy

- Flexible Pacing: Running The Same Race

- Littles, Middles, Molders, and Olders – Multi-age Learning at Journey Elementary

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director.