CBE Starter Pack 2: Meaningful Assessment

CompetencyWorks Blog

When educators begin to explore competency-based education (CBE), the CompetencyWorks Initiative is a key place to find information and ideas. It can be overwhelming to know where to start. This post is the second of a series of “CBE Starter Packs” focused on each of the seven elements of the Aurora Institute’s 2019 CBE Definition.

Competency-based education supports students to not only learn academic content, but also to apply it in different contexts and build higher-order skills. Performance assessment—grounded in tasks that measure how well students apply their knowledge, skills, and dispositions to authentic problems to produce an original product or solution which is scored against specific criteria—is a key process for producing both formative and summative evidence of student ability to apply their learning. Clear criteria for what students need to know and be able to do lay a foundation for student learning and performance of those knowledge and skills.

In a CBE system, assessment is integrated as part of the learning process. Assessment for learning provides students with low-stakes opportunities to practice and self-assess what they know throughout the learning cycle. Meaningful assessment also provides students and educators with feedback they can use to improve and continue learning.

Shared, valid, and reliable definitions of proficiency come to life through meaningful systems of assessment. Competency-based systems demand assessment literacy: the ability to use meaningful assessment to design and drive powerful learning that leads toward common outcomes. Systems of assessment are intentionally developed to balance the breadth of content with enduring understanding of and the ability to apply key concepts and higher-order skills.

Like other elements of the CBE definition, assessment connects to and aligns with the other elements. While performance assessments can be implemented within a traditional system, as performance assessment practice deepens it can prompt a desire to align other parts of the learning system. For example, as assessment systems are developed to include capstone projects and portfolios with evidence of student work, the process naturally leads to rethinking traditional approaches to curriculum, pedagogy, grading, promotion and graduation, data on progress, and reporting.

As we think about what learning outcomes we care about most for all students—and what kinds of assessments will allow students to demonstrate those outcomes—we can align other practices to design equitable access to learning. In order for students to meaningfully apply their knowledge and skills, they will be exercising agency, they will need feedback and timely support along the way, and they will take different pathways to learn and create. Building relationships to get to know students gives educators insights into the funds of knowledge students bring to their learning and how to activate student assets in the learning and assessment process.

Meaningful assessment also prompts us to examine how we report on progress (whether at the individual, classroom, or system level) and how students and educators have access to and use that information in learner records, in personalized learning plans, or for planning future learning opportunities. In order for the learning and assessment system to lead to actionable, valid, and reliable evidence, assessment-literate teachers will need to calibrate their understanding of student performance through examining student work and curricular artifacts. Systems that track and show student progress will need to be operational and transparent, both for practical reasons and to ensure and monitor for equity.

Even though meaningful assessment can feel like (and is!) a big topic, there are many ways to get started.

What does meaningful assessment look like?

Example: Del Lago Academy

At Del Lago Academy of Applied Science, one of three public high schools in Escondido, CA, opportunities for meaningful assessment are integrated throughout the learning process and grading practices are aligned to communicate student achievement. Interdisciplinary projects are at the heart of instruction and assessment, supported by the organization of students into “villages” of about 100 students who move together throughout the school day to the same group of shared teachers. With a focus on science and connections to the local biotechnology industry, students have multiple opportunities to work on and demonstrate key science and engineering competencies and can deepen their skills and work readiness by earning badges for industry-level skills.

Professional learning has consistently included a focus on designing quality performance assessments and collaborative Professional Learning Community (PLC) structures. The school also implements other competency-based assessment practices, such as providing assessments when students are ready and opportunities for retaking assessments to meet expectations.

Learn more: Interdisciplinary Projects and Assessment Practices at Del Lago Academy, Del Lago Academy Learning Journey in the Assessment for Learning Project

Example: Parker Charter Essential School

At the Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School in Devens, MA, teachers regularly meet to offer feedback on units of study and assessments and calibrate to ensure consistency and high expectations. Learning within each unit of study is designed around Parker’s Criteria for Excellence. Students meet the criteria for excellence through their coursework and performance assessments. When they have sufficient evidence in their portfolio, they are ready for a gateway. A gateway is a milestone marking when a learner has proven that they have demonstrated the learning expectations for one division and have the necessary Habits of Learning to take on more challenging coursework in the next division (typically, but not always, corresponding to grades 7-8, 9-10, and 11-12), or for 12th-graders, their post-secondary path. Through a portfolio of work, a presentation of learning, and in the high school years, an independent research project on a topic of interest, the gateway and promotion by portfolio system supports each student to meet high expectations including how to be a reflective, self-directed learner.

Learn more: Celebrating Readiness for the Next Challenge: Gateway at the Parker School, Multiage Classrooms May Improve Learning, Student Experience, Inside Mastery Based High Schools: Profiles and Conversations

Student Experience “Look Fors”

Can you see these student experience “look fors” in the examples above?

- Students are involved in projects that make connections to the real-world and are assessed on student work that is meaningful and relevant to them.

- All students have opportunities to apply learning and build higher-order skills and to demonstrate mastery by showing what they know by submitting evidence of transferring knowledge and skills through performance-based assessment.

- Students know the learning goals and how they will be assessed. Definitions of proficiency are transparent and available.

- Rubrics and examples of proficient student work are used to communicate proficiency. Grades communicate student proficiency and progress.

- Students have opportunities to reflect, revise, and use assessment as part of the learning process. Feedback and data is used to improve performance and deepen understanding.

What school policies and practices support meaningful assessment?

- Structures and processes are in place to ensure that the instruction and assessments are fully aligned with the learning objectives and offer rich and frequent opportunities for students to perform at the highest possible depth of knowledge.

- Assessment literacy is developed and prioritized. Teachers are supported in using different types of assessments and providing productive feedback to students.

- Teachers build capacity in assessing both the building blocks of learning and transferable skills through performance-based assessments.Teacher-generated performance assessments are strengthened by engaging in task validation protocols.

Photo by Allison Shelley for EDUimages - Teachers engage in calibration or joint scoring of student work to ensure inter-rater reliability and that levels of proficiency are aligned to the learning goals of the system (including state standards as applicable) and shared among teachers.

- Transparency in grading provides feedback on student progress and is designed to recognize and monitor growth with consistency and reliability.

Learn More

Dig into the research and background information

- Multiple researchers have found that well-constructed performance assessments are better able to measure higher-order thinking skills while accommodating a wider variety of learning styles than standardized tests. For example, see Refocusing Accountability: Using Performance Assessments to Enhance Teaching and Learning for Higher Order Skills” by Wood, Darling-Hammond, and Neill.

- The report, How Systems of Assessments Aligned with Competency-Based Education Can Support Equity, explores how competency-based education systems must be accompanied by high-quality assessments and assessment systems to deliver on critical equity aims to ensure that all students are supported in meeting key learning and development targets. (See also this blog summary of the report.)

- In Successful School Restructuring: A Report to the Public and Educators, Newmann and Wehlage identify three characteristics for authentic learning, which can inform the design of learning and assessment in a CBE system. The characteristics are “the construction of knowledge, through the use of disciplined inquiry, to produce discourse, products, or performances that have value beyond school” (see pp. 15-18 in the original report or pp. 3-6 in Authentic Instruction and Assessment, which also includes a chapter summarizing the research).

Explore Examples and Resources

- The blog post, Keeping Students at the Center with Culturally Relevant Performance Assessments, explores examples from Hawai’i and California and offers considerations for designing for culturally responsive practice.

- The Center for Assessment classroom assessment learning modules support assessment literacy and can be used in professional development.

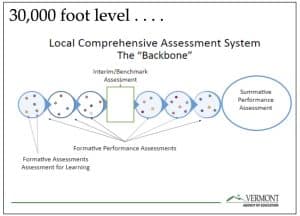

- The issue brief, Strengthening Local Assessment Systems for Personalized, Proficiency-Based Education: Strategies and Tools for Professional Learning, describes the Vermont Agency of Education’s efforts to support the creation of high-quality local comprehensive systems of assessments. It is full of practical tools and resources.

- A collection of articles and resources about performance assessment can be found in Performance Assessment: Fostering the Learning of Teachers and Students including case studies, example tasks and a Performance Assessment Glossary.

- Using Performance Assessments to Support Student Learning is a report by the Learning Policy Institute. There is also an accompanying webinar and case studies of LA, Oakland, and Pasadena along with a video series about student capstones.

- A sampling of CompetencyWorks site visit blogs about assessment include: Proving Your Learning Through Portfolio Presentations, Farmington Area School District Shifting the English Department to Competency-Based Assessment, Structuring Standards-Based Instruction and Assessment at Vancouver iTech, Performance-Based Assessment in Action at a Danville, KY Middle School.

- The CBE Design Principle 2 Rubric is a resource from the book, Unpacking the Competency-Based Classroom, in which Vander Els and Stack offer a roadmap for transforming schools in pursuit of greater equity through competency-based learning.

- Try starting by implementing a performance assessment from a task bank such as the Performance Assessment Resource Bank or MCIEA Task Bank – MCIEA. Or find inspiration in one of these five assessment blueprints or ideas for collaboration projects.

Supporting Design and Equity Principles

The information above is synthesized from key Aurora and CompetencyWorks publications. In particular, Designing for Equity: Leveraging Competency-Based Education to Ensure All Students Succeed and Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education.

Key Principles for Meaningful Assessment:

- Equity Principle (p. 29): Develop Shared Pedagogical Philosophy Based on Learning Sciences

- Equity Principle (p. 35): Ensure Consistency of Expectations and Shared Understanding of Proficiency

- Quality Principle #8 (p. 63): Design for the Development of Rigorous Higher-Level Skills

- Quality Principle #11 (p. 77): Establish Mechanisms to Ensure Consistency and Reliability

Get Started

Reflecting on your own or with your team, school, district, and/or community is a great way to identify current assets to build on. Use these questions in your work to develop an assessment system that is a meaningful, positive, and empowering learning experience for students and that yields timely, relevant, and actionable evidence.

- Does assessment promote a positive experience for students, including timely and accurate feedback that supports their learning?

- How do students share their work with each other through collaborative work, peer review, etc? Are there portfolio reviews, exhibitions, or other opportunities where students present to authentic audiences, such as members of the community, parents, or other students?

- What types of processes are in place to support educators in building a shared understanding of proficiency of academic skills, social emotional skills, and habits of success?

- How do teachers share their work together through designing and validating tasks, calibrating student work scoring, revising tasks, sharing instructional strategies, etc.?

Once you have an idea of strengths to build on or areas in need of new ideas, what will you do next, both in the short term (think: trying one new thing) and in the longer term (think: strategic planning and systems change)? Hopefully the resources above give you models, tools, and ideas to adapt to your context or inspire new approaches that work for your community.

Good luck! If you are looking for additional resources, try browsing past posts on the CompetencyWorks Blog with its many stories of lessons learned by innovators and early adopters from across the field of K-12 competency-based education.

Read the Other Posts in the Starter Pack Series

- CBE Starter Pack 1: Students are Empowered Daily

- CBE Starter Pack 3: Timely, Differentiated Support

- CBE Starter Pack 4: Progress Based on Mastery

- CBE Starter Pack 5: Learn Actively With Varied Pathways and Pacing

- CBE Starter Pack 6: Equity Strategies Drive Culture, Structures, and Pedagogy

- CBE Starter Pack 7: Establish Rigorous, Common Expectations with Meaningful Competencies

Laurie Gagnon is the Aurora Institute’s CompetencyWorks Program Director.