A Primer to Indigenous Education: A Case for Tribal Competency Crediting

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the first of two blog posts focused on the intersection of Native education and competency-based education. The series focuses on how education leaders may start to formally honor Indigenous knowledge in ways that revitalize and sustain Native communities.

The Aurora Institute updated its definition of competency-based education in 2019 to include the need to make learning culturally relevant to students. Seeking to identify the skills and abilities of students through competency-based measures assists in the promotion of equity-based practices as we look to shift away from educational systems that minimize the value of student agency. The shift to developing competency-based measures in education may have a significant benefit to Tribal communities, as Tribal systems of education have always been present, but not recognized through public education entities.

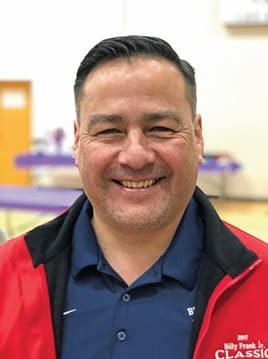

Jerad Koepp and Mike Smith work collaboratively in Washington State to enact sustainable change in systems of education for Native students and communities. Jerad, the Native Student Liaison for North Thurston Public Schools and the Washington State Teacher of the Year for 2022, has served Native students and community members for the past eight years. Mike, who is currently the principal of Rochester High School in Rochester, Washington, has served as a teacher, assistant principal, and principal for the past 15 years. Mike’s doctoral dissertation investigated Indigenous leaders’ perceptions of collaborative trust with school officials in Washington State. The knowledge held by Mike and Jerad has been shared both locally and nationally in the form of professional development, seminars, and formal presentations.

With a lack of Native cultural visibility in public education spaces, combined with historically low graduation rates at national and local levels, it is not difficult to see that our education system is not meeting the needs of Native communities and students. The ratio of Native educators to students is often lower than 1:100, making sustainable change difficult to achieve. Native educators comprise less than 1% of the educational field nationally, as well as within Washington State, highlighting the importance of allies. Despite being overlooked and understaffed, Native educators accomplish a lot when working with dedicated and educated allies in a variety of positions within public education. Our story demonstrates the transformative role that educators, administrators, policymakers, and Tribal leaders can play in supporting our diverse Native student populations.

In these two blog posts, you will see familiar traditional professional approaches and western academic traditions, but also desettling and decolonizing research and practices. The comforts of settler education can’t address the persistent challenges and inequities built into public education. You will read how two worlds can reconcile and heal in the process of improving educational equity. These articles will inform, challenge, illuminate, and inspire educators to be allies for change. Public school officials, legislators, and leaders of Native communities must unite to create sustainable changes for Native youth in public school spaces. This series of blog posts will assist you in this journey, following in the footsteps of the historic work being achieved in Washington State.

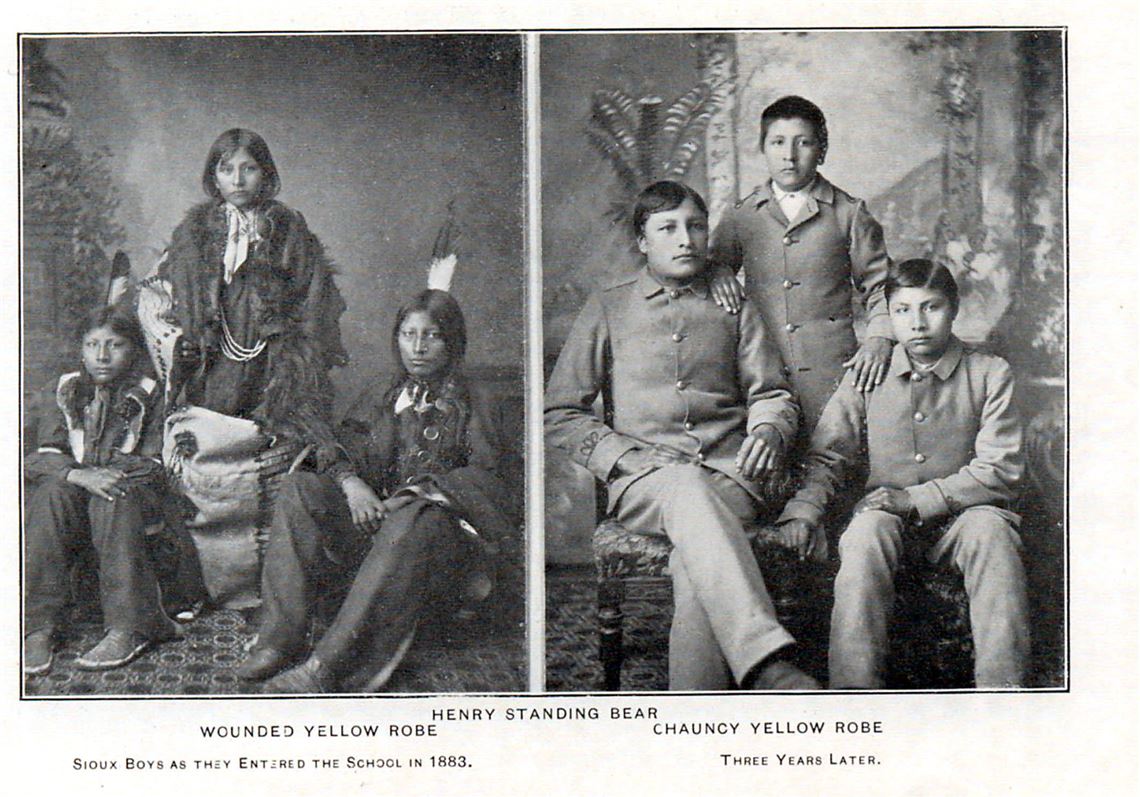

Historical Federal Policies and Practices: Indigenous Education

Formal systems of education implemented by the United States government were designed to assimilate Native youth, forcing a rejection of their Indigenous identity. The boarding school system ignored traditional ways of teaching and learning inherent to Native communities and replaced them with colonizers’ values and education. This campaign to forcefully integrate students into the Western culture was often accompanied by significant verbal, physical, and sexual abuse, as well as death. In the United States, the last boarding school was closed as recently as the 1970s. The lasting effect of the boarding school system created generational trauma, including a lack of trust in the public education system’s ability to educate Native youth.

The United States Government has long recognized the shortcomings of the public education that has been provided for Indigenous communities, as outlined in the Meriam Report (1928) and the Kennedy Report (1969). However, little has been done at a national level to address the concerns outlined in these documents. In 1975, Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Assistance Act, recognizing the importance of Tribal self-determination and sovereignty in public education spaces.

Washington State Legislative Actions: Creating The Conditions For Change

While school district leaders do not have a firm grasp of Native education, a small handful of education, legislative, and Indigenous leaders are changing Washington State’s policies and practices to cultivate sustainable change for Native youth in public education institutions. In 2013, Washington State passed legislation approving the Since Time Immemorial: Tribal Sovereignty in Washington State curriculum. This curriculum was developed through consultation and collaboration with educators, Tribes in Washington State, and the Washington Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction. In 2015, Washington State legislators mandated the implementation of the Since Time Immemorial curriculum (SB 5433) in all public schools as an onus of responsibility on school leaders to enter into meaningful consultation with their local Tribes. The passing of SB 5433 created an opportunity for Tribal leaders and school officials to start the process of healing, reconciliation, and sovereignty-aligned school improvement efforts.

In 2019, Bill Kallappa (Makah) was nominated by Washington State Governor Jay Inslee as the first Native American on the State Board of Education. In 2021, Bill was selected as the chair of the State Board of Education, and his involvement and support for changing the education landscape have been invaluable, leading to pro-Indigenous educational momentum.

In 2019, Bill Kallappa (Makah) was nominated by Washington State Governor Jay Inslee as the first Native American on the State Board of Education. In 2021, Bill was selected as the chair of the State Board of Education, and his involvement and support for changing the education landscape have been invaluable, leading to pro-Indigenous educational momentum.

In 2020, the Washington State legislature affirmed Native student graduates’ right to wear regalia with RCW 28A.600.500. Before this legislative action, school leaders could refuse to allow students to wear culturally significant regalia (eagle feathers, woven cedar, etc.) during graduation ceremonies. While many districts allowed regalia as part of the graduation ceremony, students, families, and Native Nations had to prove the significance of the regalia to school officials for acceptance. A student’s graduation is typically a time of pride and celebration for most families, while Native families and students were still subjected to re-traumatization and shamed by racist graduation policies. Culturally ignorant policies perpetuate inequities against Native people while ignoring sovereignty. With the passing of RCW 28A.600.500, students’ inherent right to represent their heritage is now officially recognized without reprisal or dismissal from school officials.

In 2021, a series of legislative changes took place in Washington State, continuing the trend of progressive action toward the improvement of educational sovereignty and self-determination of Native communities. The most significant of these changes was the passing of HB 1356, championed by Representative Debra Lekanoff, the only Native American woman to serve in the legislature. This legislation bans the use of Native American mascots within public schools. While Washington State just recently banned the use of Native American mascots in schools, consider how they persist across the country and the effects such overt racism has on Native students. Consider the pain for a Native student living in a society that murdered their ancestors, stole their homelands, broke treaties, and banned their cultures and languages only to see a grotesque misrepresentation of their people used as a costume at a school game. In taking a moment to contemplate these common examples, it’s easy to understand why Native students are underserved in public education.

In 2021, a series of legislative changes took place in Washington State, continuing the trend of progressive action toward the improvement of educational sovereignty and self-determination of Native communities. The most significant of these changes was the passing of HB 1356, championed by Representative Debra Lekanoff, the only Native American woman to serve in the legislature. This legislation bans the use of Native American mascots within public schools. While Washington State just recently banned the use of Native American mascots in schools, consider how they persist across the country and the effects such overt racism has on Native students. Consider the pain for a Native student living in a society that murdered their ancestors, stole their homelands, broke treaties, and banned their cultures and languages only to see a grotesque misrepresentation of their people used as a costume at a school game. In taking a moment to contemplate these common examples, it’s easy to understand why Native students are underserved in public education.

The second major change to evolve out of the 2021 legislative session required educators to be versed in antiracist educational practices to maintain licensure (HB 1426). Before 2021, educators and school administrators had to accrue 100 hours of professional development every five years, with little expectations of targeted growth to improve conditions for diverse populations in Washington State. The requirement outlined in HB 1426 requires 25% of all professional development to target increasing awareness of diverse communities and cultures present inside of public school spaces.

The language of the bill also specifically targets school leaders’ professional development regarding best practices in school leadership, antiracist school paradigms, and the development of government-to-government relationships with Native leaders. In Washington State, schools are struggling to effectively implement the Since Time Immemorial curriculum, as dedicated by SB 5433. The prevailing thought was that school officials lacked the professional skill sets to engage with local Tribal leaders towards meaningful change, due to a lack of knowledge regarding the Native experience in public education. HB 1426 now mandates school leaders to complete professional development on creating and sustaining government-to-government relationships with local Tribes.

Next Steps in Legislation: Competency-Based Learning Directed by Indigenous Communities

In Washington State, school leaders have a responsibility to enter into consultation with local Tribes regarding continuous school improvement efforts. Public school systems also have a responsibility to assist in “nation-building.” The critical thought behind the term “nation-building” is that school officials should understand the needs and desires of the local Indigenous Nation and reflect those needs through instructional or programmatic changes.

A major component of reflecting the needs of your local Tribe is recognizing and honoring the formal systems of learning which have existed in Native communities since time immemorial. In recognition of this learning, under proposed legislation HB2090, Washington State legislators could authorize Indigenous Nations the ability to grant high school credit towards graduation through Native students’ involvement with Tribal-directed learning opportunities. The process of granting credits for Tribal activities exists in Washington State, under a very limited scope.

A problem that exists for many Tribal Nations is the lack of reciprocity between multiple school districts that share their students. For example, one district may honor Native competency-based crediting (also called mastery-based crediting), while another district does not. Washington state HB 2090 attempts to interrupt this practice, creating a standard expectation for all school districts to follow. Under a competency-based learning concept, external education should be aligned with state learning standards and objectives. Under this progressive policy, credits would be granted based upon the Tribes’ standards of learning, honoring Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination rights. This legislation would be a massive step forward in creating sustainable actions and solutions towards improving Indigenous student success in public education systems in Washington State.

Conclusion

Indigenous children are brilliant. Formal systems of education are still a tool of oppression if school officials fail to authentically engage with Tribal Nations in meeting sovereignty and self-determination needs. Our Nation long ago identified how public education systems are not meeting the needs of Indigenous students (Meriam Report, Kennedy Report). Indigenous communities need allies to make positive, pro-Indigenous reform happen in public education. For non-Native educators and professionals, there is power in the process, relationships, and policy. Professional ethics and leadership are of primary importance when developing cultural competencies towards the implementation of competency-based education. How leaders internalize cultural values may hinder or support the advance of culture-based, competency-based education initiatives in public schools. In our next blog post, we will investigate how stances of education leaders may influence the development of relational trust, and we will provide additional resources for pro-Indigenous local policy to be enacted in school districts.

Learn More

- Whose Standards Are We Privileging? Collaboration and Consultation with Indigenous Leaders

- Getting to the Heart of Equity in Education

- Sustaining and Sharing Cultural Heritage at the Tatitlek Community School

- Teaching through the Culture: Native Education in a Performance-Based System

Jerad Koepp (Wukchumni) has 12 years of professional experience in Native American education. He has been recognized as 2022 Washington State teacher of the year and 2022 ESD 113 regional teacher of the year. Jerad earned his Master’s in Teaching from the Evergreen State College, specializing in Native Education, and is certified in history and social studies. Since 2013, he has proudly served as the Native Student Program Specialist for North Thurston Public Schools, providing cultural and academic support for approximately 250 Native American students from over 50 Tribes, nations, bands, and villages. He also trains and supports district staff, serves as a liaison to local Tribes, and leads the development of his district’s growing Native Studies program. Jerad serves on the board of the Western Washington Native American Consortium as secretary. He has made presentations to many professional groups and has played a key role in creating district policies supporting Native education, culture, and students.

Jerad Koepp (Wukchumni) has 12 years of professional experience in Native American education. He has been recognized as 2022 Washington State teacher of the year and 2022 ESD 113 regional teacher of the year. Jerad earned his Master’s in Teaching from the Evergreen State College, specializing in Native Education, and is certified in history and social studies. Since 2013, he has proudly served as the Native Student Program Specialist for North Thurston Public Schools, providing cultural and academic support for approximately 250 Native American students from over 50 Tribes, nations, bands, and villages. He also trains and supports district staff, serves as a liaison to local Tribes, and leads the development of his district’s growing Native Studies program. Jerad serves on the board of the Western Washington Native American Consortium as secretary. He has made presentations to many professional groups and has played a key role in creating district policies supporting Native education, culture, and students.

Dr. Michael Smith has served in public education for the past 15 years, ten of which have been in school administration. Currently he is the principal of Rochester High School in Rochester, Washington. For the past five years, Michael has worked alongside Native leaders in Washington State to bring forth sustainable educational change for Indigenous communities. His doctoral dissertation focused on Indigenous leaders’ perceptions and experiences working with educational leaders, identifying the skills and dispositions required to lead transformative change. He has been fortunate enough to share his research with colleagues through local, state, and National conferences and writings. Michael is supported by his wife, Ashleigh, and his loving daughter, Avileigh. If you want to collaborate or learn more, Michael welcomes you to email him at [email protected]

Dr. Michael Smith has served in public education for the past 15 years, ten of which have been in school administration. Currently he is the principal of Rochester High School in Rochester, Washington. For the past five years, Michael has worked alongside Native leaders in Washington State to bring forth sustainable educational change for Indigenous communities. His doctoral dissertation focused on Indigenous leaders’ perceptions and experiences working with educational leaders, identifying the skills and dispositions required to lead transformative change. He has been fortunate enough to share his research with colleagues through local, state, and National conferences and writings. Michael is supported by his wife, Ashleigh, and his loving daughter, Avileigh. If you want to collaborate or learn more, Michael welcomes you to email him at [email protected]